One of the best of the annual meteor displays will be reaching its peak this week — the annual Leonid meteor shower.

While the Leonid meteor shower has a history of putting on stupendous displays, this year will not be one of them; at best 10 to 15 meteors per hour may be seen. This year is a bit unusual in that the Leonids are expected to show two peaks of activity, one on Saturday morning and another on Tuesday morning (Nov. 20).

In the public mind the term " meteor shower " conjures up a vision of shooting stars streaming through the heavens like rain. Such meteor storms have indeed occurred, when tens of thousands of meteors per hour flare into view. But most showers are a thousand times weaker.

Watching one consists of lying back, gazing up into the stars, and waiting. A very good shower will produce about one meteor per minute for a given observer under a dark country sky. Any light pollution or moonlight can reduce the count considerable.

This year the moon will not be a problem for the Leonid meteor shower. It will set well before the constellation Leo, where the meteors appear to radiate out from, climbs high into the sky. [ Amazing Leonid Meteor Shower Photos ]

The Leonids are tiny, sand-grain- to pea-sized bits of rocky debris shed long ago by the comet Tempel-Tuttle. This comet, like all others, is slowly disintegrating. Over the centuries its crumbly remains have spread all along its orbit to form a moving river of rubble millions of miles wide and hundreds of millions of miles long.

The Earth's orbit carries us through this meteor stream every year in mid-November. The particles are traveling at 45 miles (72 kilometers) per second with respect to the Earth. When one of them strikes the Earth's upper atmosphere, about 50 to 80 miles up (80 to 130 km), air friction vaporizes it in a quick, white-hot streak.

Scientists believe that cometary meteoroids (such as the Leonids) are not structurally strong enough to survive their atmospheric flight and as such they cannot reach the surface of the Earth to become a meteorite.

The Leonid meteor shower's parent comet, Tempel-Tuttle, orbits the sun about every 33 years. Because of the comet's proximity to Earth from 1998 through 2002, the Leonids were producing enhanced rates ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand meteors per hour. Now, with their parent comet having retreated far back to almost the far end of its orbit, near the orbit of Uranus, the Leonid rates have returned to their more typical 10 or 15 per hour.

This year the Earth will cross the orbital plane of the comet on Saturday morning. About 10 Leonids per hour might be observed during the predawn morning hours. Of greater interest will be to see what might happen when our planet passes through debris shed by the comet during a pass through the inner solar system back in the year 1400. That interaction might produce a somewhat higher hourly rate of about 15 per hour early on the morning of Nov. 20.

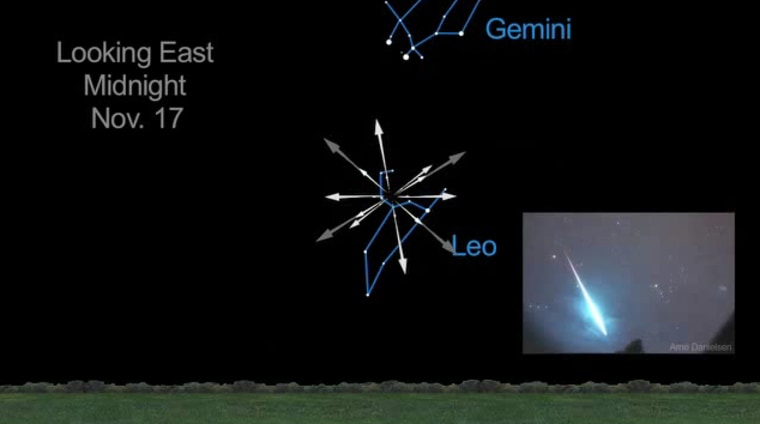

Most meteors will seem to diverge from a small area inside the star pattern famously known as the Sickle of Leo. The Sickle lies close to the northeast horizon around 11 p.m. local time, but has climbed to a point high in the south-southeast sky by sunrise. So the best views of the Leonids come in the hours between midnight and dawn as Leo gradually climbs higher into the sky.

The Leonids are white or bluish white and many are faint, though they can appear outstandingly bright, leaving glowing trains in their wake. A Leonid meteor that is roughly as bright as the brightest stars results from a meteoroid that is only a few milligrams in mass.

This year, the Leonid meteor shower occurs between two different eclipse events. The first peak of the shower will occur just days after a total solar eclipse on Tuesday (Nov. 13 EDT), with the second peak flaring up just over a week before a penumbral lunar eclipse on Nov. 28. Visit Space.com for complete coverage of all three celestial events this month.

Editor's note: If you and snap an amazing photo of the Leonid meteor shower and would like to share it with Space.com for a possible story or image gallery, send images, comments and location information to Managing Editor Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow Space.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.