Among the thousands of cases decided by the Supreme Court, just a few are instantly recognizable by name. Dred Scott. Roe v. Wade. Bush v. Gore. And, as much as any other, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

That Americans of all backgrounds and ages can rattle off the entire title of the 1954 school desegregation case demonstrates how it has grown beyond the legal and constitutional fight it raised.

Brown stands for the principle that the Constitution guarantees equality for all and that state-sponsored racial segregation is indefensible. That declaration by the court on May 17, 1954 — 50 years ago this Monday — provided the legal underpinning for much of what followed in the civil rights era.

“Brown had tremendous inspirational impact, not just for African-Americans or for civil rights activists or just in the South in 1954,” Emory University law professor David Garrow said. “It was a statement that the Supreme Court of the United States had declared racial discrimination and segregation unconstitutional and immoral.”

A unanimous Supreme Court held that the part of the Constitution guaranteeing “equal protection of the laws” meant equal treatment for blacks and whites. The decision overturned a 19th-century ruling permitting “separate but equal” facilities and accommodations for the races.

“Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” the court said in Brown.

BROWN'S FAR REACH

Through the latter 1950s, the high court issued short, often unsigned opinions extending Brown’s rationale far beyond the schoolhouse — to buses, beaches and other areas where racial separation had been a daily fact of life in the South.

Later rulings that flowed indirectly from Brown outlawed less overt racial discrimination in jobs, housing and voting rights. The ruling also echoes in later decisions advancing rights for women and the handicapped.

Brown’s influence extends even to civil rights rulings that never mention it. Gay rights activists hailed last year’s ruling that states may not punish homosexuals for having consensual sex as a statement of equality no less clear than Brown had been for blacks.

“Freedom extends beyond spatial bounds. Liberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct,” according to the 6-3 ruling by the justices.

The high court has struggled with other legacies of Brown in rulings on affirmative action and anti-discrimination programs. The court has struck down some affirmative action and quota programs as unconstitutional, while allowing other kinds of racial balancing.

A 5-4 majority quoted Brown in last year’s lukewarm endorsement of affirmative action in university admissions.

“This court has long recognized that ’education is the very foundation of good citizenship,”’ Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote. “For this reason, the diffusion of knowledge and opportunity through public institutions of higher education must be accessible to all individuals regardless of race or ethnicity.”

Brown was not the first case challenging the separate-but-equal doctrine in public schools. Nor was it the only impetus for the wider push to dismantle racially discriminatory laws that followed.

Yet without Brown, change surely would have been slower and more difficult, University of Southern California law professor Erwin Chemerinsky said.

As important as Brown was for the practical task of ending a discriminatory educational system, the ruling should be remembered as an ideal for the nation’s highest court itself, lawyers said.

Chief Justice Earl Warren recognized that in decreeing momentous social change, the Supreme Court had the power to do what Congress and other institutions could not or would not do, Chemerinsky said. The justices also knew their ruling would be unpopular, even beyond the segregated South.

“It is really the height of what we want our courts to aspire to,” Chemerinsky said. “Brown is the symbol of the courts at their very best.”

Brown’s shortcomings

A half-century later, it is easy to point to shortcomings in the ruling itself and in the resolve of the court and the country to abide by its promise.

Brown is short on details and contains no deadline for desegregation. A year later the court followed up with a vague statement that the work be carried out “with all deliberate speed.”

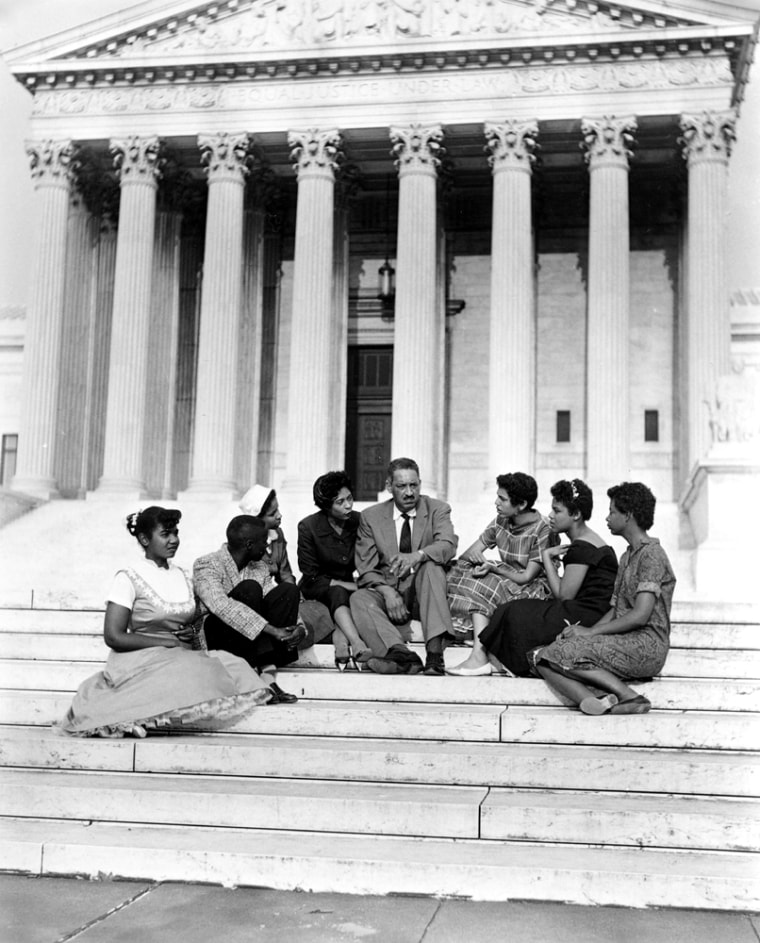

Thurgood Marshall, an NAACP lawyer who argued the case at the high court and later served as the first black justice, once observed that he had finally figured out what that phrase meant. “It means slow,” he said.

Marshall’s replacement on the court, Justice Clarence Thomas, is the only black now on the court. He entered first grade the year Brown was announced, but still attended all-black schools and lived under segregation in Georgia for much of his young life.

Thomas voted against affirmative action in last year’s case and warned of the dangers of artificially manipulating the racial makeup of any institution.

“Contained within today’s majority opinion is the seed of a new constitutional justification for a concept I thought long and rightly rejected — racial segregation,” Thomas wrote.

Dennis Archer was a junior high school student in Michigan when Brown was announced. Archer is now the first black president of the American Bar Association.

Although the struggle for equality and opportunity continues, blacks and whites must remember how profoundly the country has changed, Archer said.

“I stand on the shoulders of people I’ve never met, but have read about; those who were lynched, beaten, spat upon,” Archer said.

Now, “I can go to any hotel I choose if I’ve got the money. I can travel on any bus or any airplane.”