The trials of the U.S. military police accused of abusing Iraqi prisoners will remind many surprised Americans that the men and women who safeguard them and their liberty do not enjoy all of the privileges they have sworn to die defending.

The first of at least seven courts-martial in the scandal at the notorious Abu Ghraib detention facility, on the outskirts of Baghdad, was quickly dispensed with last week when Spc. Jeremy C. Sivits appeared before a special court-martial. Sivits’ trial would not have struck many people as anything out of the ordinary — he is cooperating with authorities and , receiving a dishonorable discharge and a year in prison.

But the other soldiers have proclaimed their innocence and will defend themselves in general courts-martial, and that is when the differences between the civilian and military criminal justice systems will become apparent to Americans who may only dimly remember what they learned in civics classes or from movies like “A Few Good Men.”

Three of them made their first court appearances last week in more serious general court-martial proceedings. If and when those soldiers eventually go on trial, Americans will get a new look at a system of justice quite different from what goes on in civilian courts.

A court-martial is more akin to a trial in a lawsuit, not a civilian criminal prosecution. It has more in common with the civil action that found O.J. Simpson responsible in the deaths of Nicole Simpson and Ronald Brown than it does the criminal trial in which he was acquitted of murder a year earlier, in 1995.

As in civil trials, the jurors — called members of the court-martial — need not agree unanimously. And as in some civil trials, there are fewer of them than the 12 people who make up a criminal jury. (Indeed, courts-martial can dispense with jurors entirely, being conducted before only a military judge.)

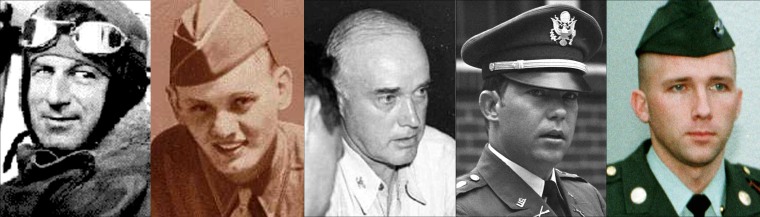

The Abu Ghraib cases are the first courts-martial of high public interest since Army Spc. Michael G. New, a medic, was convicted and discharged in 1996. New refused orders to remove the U.S. flag from his uniform and replace it with the U.N. patch when his unit was assigned to peacekeeping duties in Macedonia in 1995.

New’s case was a political cause célèbre for conservative activists, but it hinged on dry legal arguments of whether the order New disobeyed was legal and whether his trial was conducted under proper procedures. It created several thorny legal questions, some of them not yet resolved, that could come into play again, but it did not carry nearly the emotional weight that the trials of the soldiers at Abu Ghraib will.

Two scandals, one reporter

The U.S. military has conducted many famous courts-martial over the centuries. George Custer was convicted at his court-martial. But Daniel Boone and Jackie Robinson were cleared at theirs. But for sheer drama, you need go back only to 1971, when Lt. William L. Calley Jr. was convicted of leading his Army unit in an invasion of the Vietnamese village of My Lai in 1968, during which hundreds of unarmed civilians were shot to death. The massacre was uncovered by Seymour Hersh — the same journalist who helped bring the abuses at Abu Ghraib to worldwide attention with his reporting for The New Yorker last month.

Liberals and peace activists demonized Calley as a war criminal. Conservatives defended him as a soldier who did what he thought he had to do in wartime.

“If we found him not guilty it could be perceived as a whitewash, that we didn’t care about other human life if it was not Americans,” Harvey Brown, a major who served on the court, told his hometown Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph in retirement 23 years later. “If he was guilty, we were traitors.”

The verdict divided Americans as deeply as did the massacre itself.

After the court convicted Calley, “they vilified us — we were traitors, we had no business being in uniform,” Brown said in 1994. “It was a pretty scary situation. You just spent 4½ months of your life living through this, making the best decision possible.”

Calley was sentenced to life in prison, but President Richard Nixon reduced his sentence after conducting secret polls of the public. Calley served three years of house arrest before a federal judge overturned his conviction; although the conviction was later reinstated by an appeals court, Calley remained a free man. He was last known to be living in Columbus, Ga., where he was embraced by the city’s large military community. He does not talk to reporters.

Cruel and unusual punishment?

Pvt. Edward Slovik was assigned to an infantry unit when he arrived in France in August 1944. Slovik and a friend became separated from the rest of the unit two months later, turning up with a Canadian regiment before rejoining his company three days later.

After only an hour back with his unit, Slovik left, voluntarily surrendered and signed a confession of desertion. When Slovik spurned advice to destroy the document, he was arrested. He then refused a judge’s offer to drop a court-martial if he would return to duty.

Slovik was convicted of desertion in Roentgen, Germany, in November 1944 and was sentenced to death. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, rejected Slovik’s plea for clemency in December, and Slovik was executed by a firing squad on Jan. 31, 1945.

According to military historian Uzal Ent, a member of the firing squad later summarized what many soldiers thought of Slovik. “He deserted us, didn’t he? He didn’t give a damn how many of us got the hell shot out of us, [so] why should we care for him?” the soldier said.

However, other World War II veterans have championed Slovik as a conscientious objector who twice rejected the chance to save his own life to stand up for his convictions. Some pursued a presidential pardon for Slovik for decades, but it was consistently turned down, most recently by Bill Clinton in 2001.

Slovik’s story was told 30 years ago in a television mini-series, “The Execution of Private Slovik.” He was played by Martin Sheen, whose current character, the president of the United States on “The West Wing,” could clear his name, at least in the television universe.

A dreamer redeemed

As much as any person can be, William Mitchell is considered the father of the U.S. Air Force. He believed so deeply in aviation that he sacrificed his military career.

Mitchell was already 36 years old when he was first assigned to the Aviation Section of the Army Signal Corps in 1915. He was too old to undergo training at the Army’s aviation school, so he paid for his own private flying lessons.

Within a year, Mitchell was promoted to head the Aviation Section. Sent to Europe at the outset of World War I, he quickly adopted an evangelical fervor about the military supremacy of air power, personally lobbying Gen. John Pershing, the U.S. commander in Europe, to create a robust air wing as part of the American Expeditionary Force.

By the end of the war, Mitchell had shot up through the ranks to brigadier general, responsible for finding and training the Army’s pilots. But Billy Mitchell rubbed people the wrong way, antagonizing so many senior Army and Navy officers that in 1925, he had been demoted to colonel.

Mitchell saw the demotion as a judgment on the aviation service itself, and so when the Navy airship Shenandoah crashed that September, he publicly criticized the War Department (the Pentagon’s predecessor) for “criminal negligence” in letting America’s air power atrophy.

Mitchell was court-martialed for insubordination. He was convicted and suspended from duty for five years; rather than languishing in limbo, he resigned from the Army in February 1926.

Mitchell died in 1936 after publishing many works on military aviation. After his theories proved prescient, helping the Allies win World War II, he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1946. Two years later, designed on Mitchell’s outlines, the U.S. Air Force was created.

Keep those secrets

Army Maj. Gen. Robert W. Grow, a hero as an armored division commander in Europe during World War II, was a widely respected soldier who became the U.S. military attaché in Moscow after the war.

But in 1952, a Soviet agent stole Grow’s personal diary from his hotel room in Frankfurt, Germany, photocopied it and returned it so Grow would not know that it been compromised. The operation went undiscovered until excerpts of the diary appeared in the Soviet press.

Grow was court-martialed on charges of failing to guard secret information. Convicted in July 1952, he was reprimanded and suspended from command. For 50 years, his many defenders have accused the Defense Department of using Grow as a political scapegoat at the height of the Cold War showdown with Moscow.

Grow died in 1985, the only general to face a court-martial under the 1951 Uniform Code of Military Justice until 1999, when retired Maj. Gen. David Hale was reprimanded and fined after pleading guilty to conduct unbecoming an officer for having affairs with the wives of four subordinates.