A new computer program automatically determines the dates of documents from the Middle Ages. It works by looking for words and phrases that were fashionable at the time — the Ermahgerds of the era — to determine that a given document is so 1240s, for example.

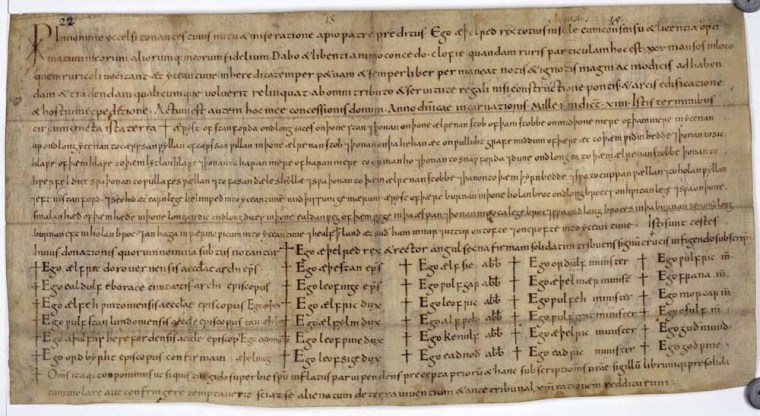

The program analyzes property deeds, called charters, written in England between the late 1000s and the mid-1400s. The charters provide a major resource for historians piecing together English history of the time period, but people didn't generally put dates on these documents until after the 1300s.

The program helps date otherwise mysterious charters, said Gelila Tilahun, a statistician at the University of Toronto who built the program while earning her doctoral degree. Plus, it IDs the memes of the times.

Tilahun hadn't even heard of the charters, which are written in Latin, before she started the project. She still isn't exactly an expert, she says. "I don't know any Latin or, you know, very little medieval history, actually," she told TechNewsDaily. But her program doesn't require her to read Latin or know history. [See also: 10 Medieval Weapons that Changed the Face of Warfare ]

Instead, Tilahun, her doctoral advisor and a University of Toronto historian gave the program a "training set" consisting of the digital files of 326 already-dated charters. (Historians have given many originally undated charters dates by looking for distinctive handwriting or mentions of names or current events.) The program scanned through the training charters, automatically identifying phrases that appeared frequently during certain time periods.

It then used the patterns it learned to guess years for digital files of other charters the researchers supplied. To test the program, Tilahun and her colleagues gave it a set of charters with known dates, finding that the program's guesses matched.

As a side benefit, the program lists the fleetingly popular phrases it finds. So what were some of the hot sayings of the Middle Ages? "Amicorum meorum vivorum et mortuorum" was common between 1150 and 1240. It's Latin for "of my friends, living and dead." Meanwhile, "Francis et Anglicis," a term of address meaning "to French and English," was used until 1204, when the British lost Normandy to the French.

The program won't replace historians, though, Tilahun said. It may miss some clues that historians find obvious. For example, if a charter has just one out-of-place word — "an extreme example would be 'iPad,'" Tilahun said — the program would ignore the incongruity, but a historian would catch it. Of course, the appearance of iPads in supposedly medieval charters would be easy for anybody to catch, but other words, names or similar clues would require expertise to find.

Tilahun and her colleagues are now trying to train their program to identify the regions charters come from, based on differences between, say, the preferred phrasings of Londoners and Devonshire-dwellers. The researchers are also interested in identifying forgeries by spotting phrases that wouldn't have occurred in a document's supposed year of origin.

Tilahun has some ideas that are farther afield than these old documents. She's looking to apply a statistical program for identifying bits of DNA that are responsible for turning certain genes on or off. It'll work much like her charters program, she said. "Essentially, it's going from text analysis to analyzing the text of, or the grammar of, our genes," she said.

Tilahun and her colleagues published their work in the December 2012 issue of the Journal of Applied Statistics. Their paper also appears in arXiv, a free repository of math and physics papers, and was highlighted in MIT Technology Review's arXiv blog.

Follow TechNewsDaily on Twitter @TechNewsDaily, or on Facebook.