More than 1 million Americans wind up back in the hospital only weeks after they left for reasons that could have been prevented — a revolving door that for years has seemed impossible to slow.

Now Medicare has begun punishing hospitals with hefty fines if they have too many readmissions, and a top official says signs of improvement are beginning to emerge.

"We're at a very promising moment," Medicare deputy administrator Jonathan Blum told The Associated Press.

Nearly 1 in 5 Medicare patients is hospitalized again within a month of going home, and many of those return trips could have been avoided. But readmissions can happen at any age, not just with the over-65 crowd who are counted most closely.

Where you live makes a difference, according to new research that shows how much room for improvement there really is. In parts of Utah, your chances of being rehospitalized are much lower than in areas of New York or New Jersey, says a report being released this week from the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care.

The AP teamed with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to explore, through the eyes of patients, the myriad roadblocks to recovery that make it so difficult to trim unneeded readmissions.

The hurdles start as patients walk out the door.

"Scared to go home," is what Eric Davis, 51, remembers most as he left a Washington hospital, newly diagnosed with a dangerous lung disease. His instructions: stop smoking. He didn't know how to use his inhaler or if it was safe to exercise, until a second hospitalization weeks later.

There is no single solution. But what's clear is that hospitals will have to reach well outside their own walls if they're to make a dent in readmissions.

Otherwise a slew of at-home difficulties — confusion about what pills to take, no ride to the drugstore to fill prescriptions, not being able to get a post-hospital check-up in time to spot complications — will keep sending people back.

"This is a team sport," says readmissions expert Dr. Eric Coleman of the University of Colorado in Denver. It requires "true community-wide engagement."

Pushed by those Medicare penalties, hospitals are getting the message.

"It's made hospitals go, 'Oh my gosh, just because they're outside my door doesn't mean I'm done,'" said nurse practitioner Jayne Mitchell of Oregon Health & Science University, who heads a new program to reduce readmissions of patients with heart failure.

STORY: Helping patients help themselves saves money

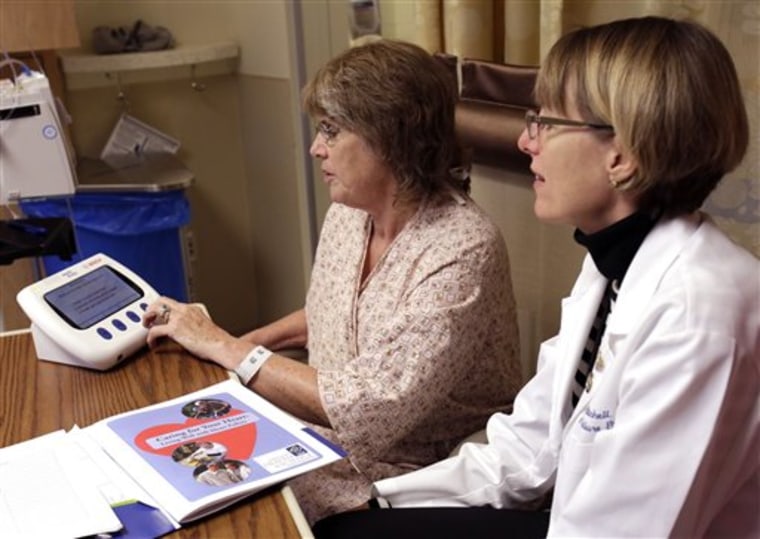

In a pilot test, her hospital is sending special telemedicine monitors home with certain high-risk patients so that nurses can make a quick daily check of how these patients are faring in that first critical month.

Too often, families don't realize that many readmissions can be prevented.

In Fort Washington, Md., Reggie Stokes started asking questions after his 84-year-old stepmother was hospitalized four times in a row, for transfusions to treat a rare blood disorder. He found a specialist in another city who said a bigger dose of a common medication is all she needs.

The hospital "could have helped her and saved money" by doing that legwork, Stokes said. His advice: "You have got to go out and do research for yourself."

That's hard when you're feeling ill, said Lincoln Carter, 50, of New York, who didn't think his pneumonia was under control when the hospital discharged him.

But, Carter said, "I didn't even really know the questions to ask." Nor could he get to his regular doctor's office. When "you can't breathe, the last thing you want to do is sit on the subway." A few days later, he was back in the hospital.

Patients don't have to be powerless, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation this week begins an effort called "Care About Your Care," which offers consumers tips to guard against unnecessary readmissions.

"Everyone has to understand their role in improving the quality of care, including families," said Dr. Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, the foundation's president. "This could be a time when we turn the corner."

Rehospitalizations are miserable for patients, and a huge cost — more than $17 billion a year in avoidable Medicare bills alone — for a nation struggling with the price of health care.

Make no mistake, not all readmissions are preventable. But many are, if patients are given the right information and outpatient support.

The new Dartmouth Atlas evaluated Medicare records for 2008 to 2010, the latest publicly available data, to check progress just before Medicare cracked down. In October, the government began fining more than 2,000 hospitals where too many patients with heart failure, pneumonia or a heart attack had to be readmitted in recent years.

"Change is hard and comes slowly," said Dartmouth's Dr. David Goodman, who led the work.

Of seniors hospitalized for nonsurgical reasons, 15.9 percent were readmitted within a month in 2010, barely budging from 16.2 percent in 2008. Surgery readmissions aren't quite as frequent — 12.4 percent in 2010, compared with 12.7 percent in 2008. That's probably because the surgeon tends to provide some follow-up care.

Medicare's Blum told the AP that the government is closely tracking more recent, unpublished claims data that show readmissions are starting to drop. He wouldn't say by how much or whether that means fewer hospitals will face penalties next year when the maximum fines are scheduled to rise.

But by combining the penalties with other programs aimed at improving these transitions in care, "we have now changed the conversation," Blum said. "Two years ago, the response was, 'This is impossible.' Now it's, 'OK, let's figure out what works.'"

Hence interest in the geographic variation.

Some 18 percent of nonsurgical patients, the highest rate, are readmitted within a month in the New York City borough of the Bronx. Rates are nearly that high in Detroit, Lexington, Ky., and Worcester, Mass.

Yet the readmission rate in Ogden, Utah, is just 11.4 percent. Half a dozen other areas — including Salt Lake City, Muskegon, Mich., and Bloomington, Ill. — keep those rates below 13 percent.

For surgical patients, Bend, Ore., gets readmissions down to 7.6 percent.

Some studies suggest part of the variation is because certain hospitals care for sicker or poorer patients, especially in big cities. Yet Minneapolis, for example, has readmission rates just below the national average. Goodman said whether local doctors' stress outpatient care over hospitalization, and how many hospital beds an area has play big roles, too.

New problems

Readmissions don't always happen because the original ailment gets worse. It could be a new problem — the pneumonia patient who's still weak and falls, breaking a hip.

Yale University researchers recently reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that people face a period of overall vulnerability to illness right after a hospitalization, because of weakness, sleep deprivation, loss of appetite and side effects of new medications.

But ask returning patients what went wrong, and Coleman, the readmissions expert, said nonmedical challenges top the list.

New York's Montefiore Medical Center now sends uninsured patients home with two weeks' worth of medication so they don't have to hunt an affordable place to fill a prescription right away, said Dr. Ricardo Bello, a cardiac surgeon.

In the nation's capital, Dr. Kim Bullock recalled her frustration with a diabetic hospitalized nine times in one year in part because of transportation. He felt too lousy to ride two buses and the subway to the nearest Medicaid clinic for regular care.

"Start from their reality," said Bullock, an emergency room doctor and family physician. Without the right community connections, "they will just stumble along."

Another hurdle: The Dartmouth study found fewer than half of patients saw a primary care doctor within two weeks of leaving the hospital.

Barbara McCoy tried. A New York hospital lowered the 44-year-old diabetic's dangerously high blood sugar and told her to call her own doctor immediately about how to prevent a recurrence. But she couldn't get an appointment until the following month. A week later, McCoy's blood sugar soared again, and she raced back to the emergency room.

This time, the hospital pulled out the stops during a weeklong stay. A nutritionist offered intense diet advice. An endocrinologist changed her medications. She was taught how to safely adjust her own insulin.

"But they waited 'til it spiked again to do these things," McCoy said. "Why couldn't they have done all that the first time? I don't understand."

Related: