The cow brains should arrive any day now.

If all goes as planned, dozens of plastic-bagged specimens each day will be delivered from surrounding states. Technicians will stick on a bar code, and delicately slice a sliver of neural tissue, which will be puréed into a pink slurry and fed into a $150,000 robot. After a few hours, tiny samples -– now mere dabs of liquid -- will tell a crucial tale. If the samples are clear, all is well. If yellow tints appear, the country may have another case of mad cow disease.

Here at the Colorado State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, and at 11 similar labs across the country, everyone hopes one of those yellow dabs never appears. But it’s a very real possibility as the Department of Agriculture begins to collect between 201,000 and 268,000 brain samples from mostly sick and dying cattle within the next 18 months. Those tiny dots, the federal government and many researchers believe, will tell us whether the country is safe from mad cow -– or needs stronger efforts to ward off a deadly disease.

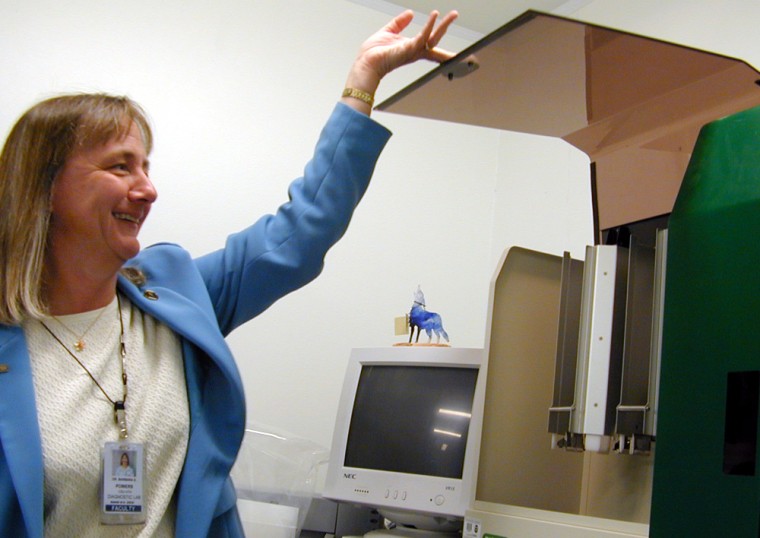

“If we have it in this country, that’s the system that’s going to detect it,” says Barbara Powers, the lab’s director.

Seeking 'confidence'

On Tuesday, the U.S. Department of Agriculture begins the much-debated $70 million testing program for bovine spongiform encephalopathy, as mad cow is formally called. After initial reluctance, the government and the beef industry settled on this broad one-time effort to determine to what extent, if at all, BSE has infected the U.S. herd of nearly 100 million cattle.

Already this year the government has tested some 15,000 cows, seeking to reach what it calls a "confidence level" that the disease isn’t present.

Most cattle to be tested -- sick and dying animals -- are not destined for the human food chain anyway, though some 20,000 apparently healthy older cattle will be sampled. Pointing to recommendations from outside advisers and a panel of experts convened by Agriculture Secretary Ann Veneman, USDA says they have crafted the best way to hunt for the disease.

"Whatever the prevalence is in this country, this is the target population in which we'll be able to find it," says USDA spokesman Ed Loyd.

But critics of the USDA's "targeted surveillance" program say the testing falls short of a comprehensive effort and will exclude millions of cattle that should be checked.

Lapses in handling

The critics point to a string of potentially troubling shortfalls in the government’s handling of mad cow. First, the USDA asserted the single infected Washington state cow was a downer, unable to walk, which helped reveal its illness; that claim was later upended. Then in April, a Texas cow showing possible signs of nervous system disorder was sent for rendering without being tested. The agency has yet to explain why. In May, the agency acknowledged at least 7 million pounds of banned Canadian beef had entered the country, an embarrassment that prompted some lawmakers to demand Veneman’s ouster.

At the same time, the agency in April rejected a request from a small meat packer, Creekstone Farms Premium Beef, to conduct its own private BSE tests so it could re-open sales to Japan, which tests all its cattle for mad cow and wants all American beef imports tested. The USDA said private tests would be inappropriate, which enraged the agency's critics -– and heightened concerns that the handling of mad cow has been botched. Worse, critics charged, the developing policy on mad cow emerged as final rules, with little or no public review.

“They just decided to define it in a way that says, ‘We don’t have to talk to the public at large,’” says former USDA undersecretary Carol Tucker Foreman, now director of food policy for the Consumer Federation of America. “When you do decisionmaking in a very small room, talking only to yourself and other like-minded people, you do dumb things.”

A precise protocol

The politics of mad cow have yet to make their way inside the chain-link fence that protects the Colorado diagnostic lab, situated on a dusty street amid sheep pens, watched by video cameras, accessed with staff badges handed out only after an FBI background check.

The facility is more familiar than most with handling diseases like this. For years, it tested deer and elk for chronic wasting disease, an affliction caused by the same sort of malformed prion proteins thought to cause BSE. Detection of the two diseases is essentially the same. Powers' staff field-tested equipment that will be used to process mad cow samples across the nation. While other labs have scrambled to get ready, the Colorado team is simply waiting for the first samples to arrive.

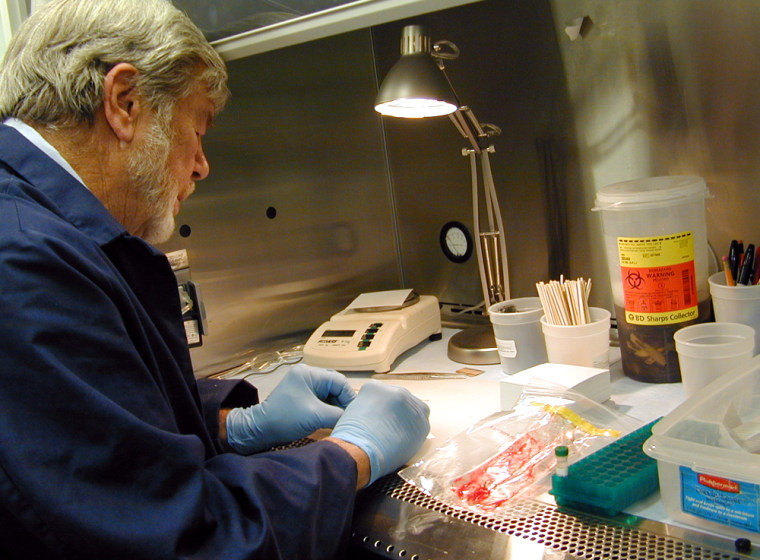

When a cow brain does show up, a technician will isolate it under a biohazard shield and go to work. The brain stem is sliced open; a tiny notch of vagus nerve, which connects the brain to vital organs, is removed, weighed and dropped in a vial. Used only once, Teflon-coated blades used to cut samples can never be laid down and must go straight into a disinfection container. Two technicians can turn out about 50 samples an hour.

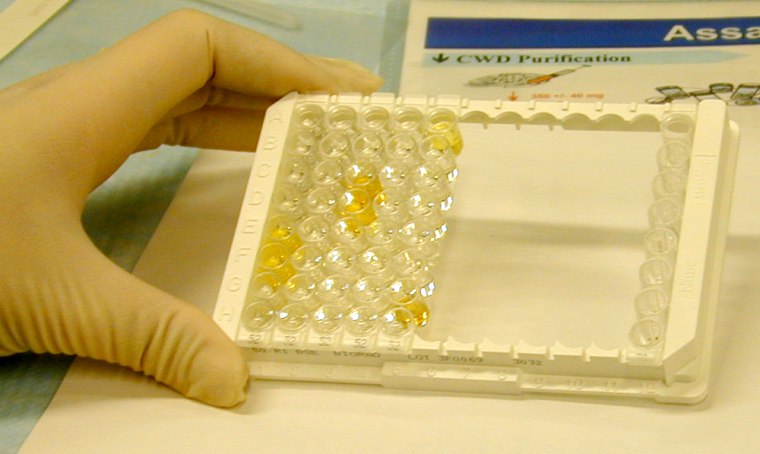

Samples go into a ribolyzer, a sort of high-tech grinder that turns them into a uniform soup, and are then paced through half a dozen mostly automated steps required for the Elisa protocol, one of two methods that offers a rapid preliminary result. Up to 96 samples can be processed at a time.

A yellow positive is easily viewed among the clear samples, though a computer optically confirms each result. Positives will be sent on to the USDA’s National Veterinary Services Laboratories in Ames, Iowa, for confirmation using a far more precise technique; immunohistochemistry, or IHC, is all but foolproof -– but requires up to two weeks as glass slides of brain tissue are carefully prepared. The USDA says it will disclose initial positives as soon as any are found.

Powers’ lab should be able to process some 500 samples per day, well beyond what she expects to receive from the government: “I don’t think they’re going to be able to collect them out in the field that fast.”

The entire process is delicate and precise, a world away from the bolt guns and saws of the slaughterhouse. The only nod to the commercial pressures that underlie mad cow testing is the lab’s turnaround time. Samples brought in by noon are to be processed by day’s end, so the dead cattle from which the brains were scooped can be buried, rendered or, potentially, sent along to the supermarket aisle.

But the only way scientists will identify these animals is through bar codes that ties a sample to its source, information that will be tightly held by the state and federal agriculture agencies. “We don’t even know where these animals are coming from,” Powers says.

Tests will occur across the nation. In March, the USDA chose public labs in Colorado and six other states: California, Georgia, New York, Texas, Washington and Wisconsin -- spread out to minimize shipping distances. In mid-May, it added Florida, Minnesota, Kansas, Kentucky and Pennsylvania. In late May, details were still not clear about exactly how samples would be distributed.

Food safety or animal health?

One place, the agency made quite clear, testing will not occur: private labs, either at beef companies like Creekstone or at facilities like the Marshfield Clinic, a respected Wisconsin medical center that conducts private food safety testing but has been barred from the mad cow effort. While official tests may cost upwards of $100 per cow, Creekstone said it could conduct tests for less than $20 per head. But government officials, and scientists like Powers, bristle at the notion of private testing -– even with oversight from a public lab.

After all, officials note, these tests are meant to find whether other mad cow cases exist in the country. It is about science and animal health, they unfailingly point out, not food safety -- which they claim is protected by numerous rules put in place since last December, along with Food and Drug Administration regulations on cattle feed. The rules call for removal of the highest-risk materials, like a cow’s spinal cord, from the human food chain. When supermarkets found meat from the lone infected Holstein had made it into shoppers’ carts, officials quickly pointed to evidence that animal muscle doesn't contain the deformed prions believed to cause mad cow’s equivalent illness, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, in humans.

But in a recent memo, the agency directed veterinarians from its Food Safety and Inspection Service, not its animal health division, to collect all samples from federally inspected plants. The agency insists its food safety staff are simply helping with an animal health effort, but critics believe the two issues can’t be separated. “I think that’s ridiculous. Of course it’s a food safety measure,” says Jean Halloran, director of the Consumer Policy Institute at Consumers Union. “If you test the brain and it’s positive, then that’s an animal that shouldn’t go into the food supply.”

Will more cases be found? “My hope is no,” says Wayne Cunningham, Colorado’s state veterinarian. “But when you talk about sampling large numbers … I would be strongly surprised if we don’t find one or two more.” Most everyone tied to the beef industry shares that belief, but they warn against hasty conclusions should additional positives appear. One repeated argument against private tests is that it would allow companies to reveal test results without government oversight.

Positive results don't necessarily mean the food supply is unsafe. France discovered 137 cases last year as French consumers kept happily eating beef; Spain found 167. But in these countries, and others, almost every older cow is tested -- up to half of the slaughter population -- so chances are excellent almost every case can be detected.

Even most of those who want expanded U.S. testing plans don’t expect the USDA to go quite so far. For one thing, the United States slaughters most of its cattle under 20 months, thought to be the youngest age that BSE can be detected.

Still, Americans slaughtered some 35 million cattle last year; if every cow over 30 months was tested, it would account for perhaps 3 million. With so many animals at risk, some scientists intimately familiar with diseases like mad cow believe more testing -- at least for a couple years -- is essential to protect public health.

"You have to do it. Otherwise, you never know for sure," says Pierluigi Gambetti, director of the National Prion Disease Surveillance Center, in Cleveland, Ohio, which tracks outbreaks of diseases like the human equivalent of mad cow. "You look at testing in the United States, compared to European nations, you don’t feel so comfortable, I think."