The relationship between African Americans and the U.S. military has long been a love-hate bond, a tango of contradiction that's lasted through several foreign wars and the nation's own civil war.

With the Memorial Day observance just past and the 60th anniversary of D-Day this weekend, we’re reminded again of the sacrifices of the nation's veterans, but the contributions of many of those veterans have often flickered just below the radar of popular recall.

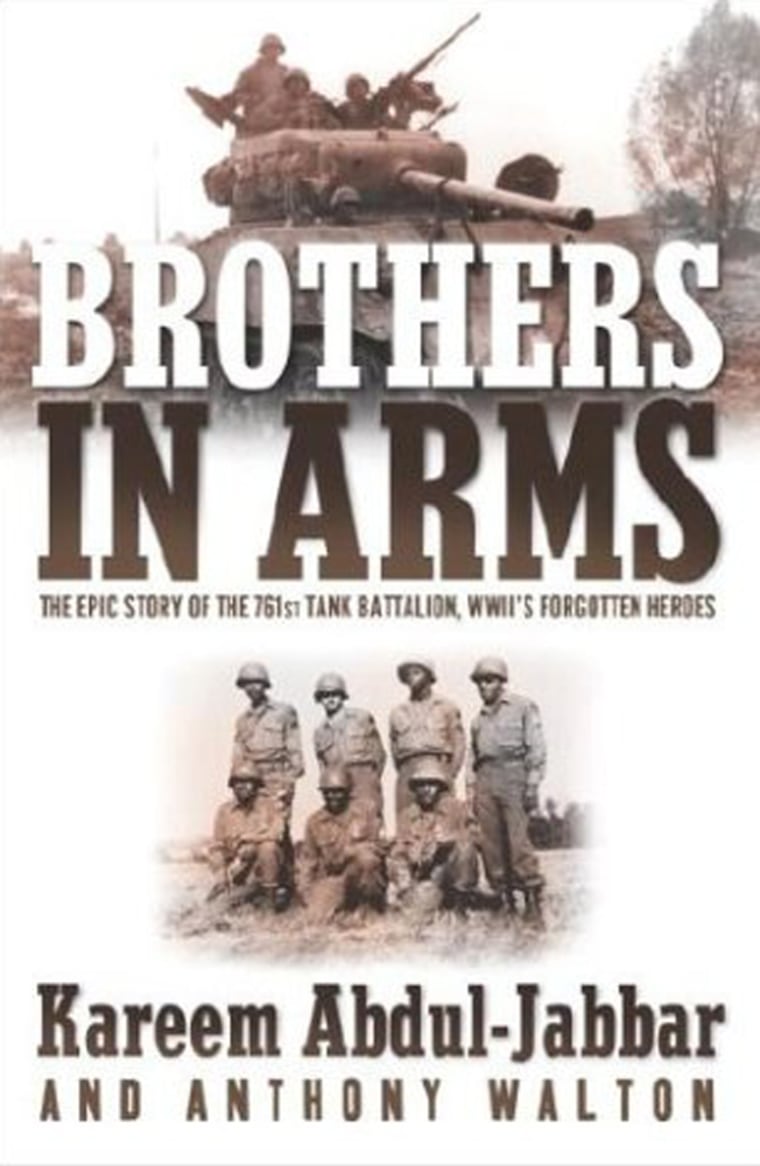

Authors Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Anthony Walton have tried to correct some of this historical amnesia with “Brothers in Arms,” an insightful, highly readable story of a World War II tank battalion that reinforced the U.S. forces in the historic Normandy invasion with pivotal support and a valor made all but invisible by the segregation of the times.

The book explores the exploits of the U.S. Army’s 761st Tank Battalion, created by the War Department (now the Defense Department) in April 1942, mostly as a public-relations gimmick to strengthen black support for the fledgling war effort.

“Brothers” is clearly a labor of love. Abdul-Jabbar, whose father fought in World War II, has a commendable grasp of the complexities of military terminology and history (not surprising for a college graduate with a degree in history). His latest book — co-written with journalist and Bowdoin College writer-in-residence Anthony Walton, author of “Mississippi: An American Journey” — reflects solid scholarship, impressive research and an evolving style.

Trial by fire at home

The story they recount is bittersweet modern Americana. The men who would form the 761st developed a camaraderie born of their status as black American soldiers in the still-segregated armed forces, and another bond as “tankers,” soldiers who traveled and fought in tanks that were confining and often dangerously overmatched by Nazi Panzers.

During their training in Texas, Louisiana and Virginia, the men of the 761st survived trial by fire before they ever got to Europe; in many ways the bigotry they encountered at home equaled the dangers they were to experience as soldiers overseas.

“Brothers in Arms” offers a sad catalog of Jim Crow in uniform: The soldiers of the 761st and other black recruits were called “Mrs. Roosevelt's niggers” by enlisted men and officers alike, a reference to the first lady's insistence that black Americans be allowed to fight the war alongside white Americans; they weren't allowed to fire live rounds during training, unlike their white counterparts; they were subject to the bigotry of the local police and citizens, sometimes — too often — to the point of death at the hands of those police or citizens.

This dangerous limbo might have kept up for the rest of the war but for the war's shifting tide, and the potential for serious reversal of fortune for the Allies. Faced with near-Pyrrhic victories in Italy and stalemates in the Pacific, the Allies set in motion the scenario that would bring the 761st to an important place in American military history.

At the Teheran Conference in late 1943, the Allies began to plan for the invasion of Europe for the following spring. The next six months were crucial for the Allies — who began to gain traction with victories at Anzio, Rome and in the Pacific — and for the men of the 761st, who distinguished themselves in training.

12 hours notice

On June 6, 1944, Operation Overlord, the greatest invasion in the history of modern warfare, began. And on June 9, the 761st Tank Battalion got its alert-status orders —12 hours notice — to prepare for deployment to Europe, ultimately to become part of the Third Army, commanded by the irrepressible, mercurial Gen. George Patton.

In about four months, the authors report, the 761st “would not only become the first African American armored unit in the nation's history to land on foreign soil; it would also become one of the first black combat units in the modern Army to fight side by side with white troops.”

With so much customary focus on the date of the initial assault on the beaches of Normandy, it's perhaps easy to see D-Day as a single event and overlook the ways in which it was the first evidence of the process of the liberation of Europe, one in which the 761st battalion took part.

In November 1944, months after the invasion started, the 761st became part of the subsequent but equally indispensable wave of troops who fought and died in France after D-Day, with the unit's casualties said to have been nearly 50 percent.

Big view, ‘small ball’

Abdul-Jabbar, the author of four previous books, has clearly grown in confidence and authority as a writer. He and co-author Walton have deftly combined an overview of black participation in World War II — the domestic social conditions, the international developments — with an ability to play “small ball,” focusing on the lives and exploits of three members of the 761st and how they typified the struggles of African Americans in a difficult time.

“Brothers in Arms” is filled with a range of lesser-known facts about the war’s undersung warriors. Here, for example, is what may be the fullest accounting of the actions behind and the consequences of the court-martial proceedings of one John Roosevelt Robinson, who would go on after World War II with a different first name — Jackie — to fight a war in a whole different arena.

Ironically, even after the war, the veterans of the 761st failed to gain traction in the history books, possibly because of intentional sabotage of the historical record.

“The Army of that time, and particularly the officer corps, was heavily populated with white Southerners, and there is reason to believe that many lost records, valor citations, and petitions for recommendation were deliberately misplaced,” the authors recount.

“Like the Ancient Mariner of Coleridge's poem, the battalion's members found themselves with an anguished tale they urgently wanted to tell but with no one to listen to or believe them.”

But the authors of “Brothers in Arms” have gone a long way to amending this gap in the roll call of those who fought and died as part of perhaps the most pivotal event in modern history.