Their lives reflect the painful, promising diversities of America, spanning north and south, black and white, young and old, jazz to rock and roll — and every variation on the American theme in between.

From one of Minnesota's most enduring sons, a Duluth-born singer who changed his name before he changed modern music, to Bix Beiderbecke, a ne'er-do-well trumpeter from Iowa who helped revolutionize jazz in the ’20s; from Robert Johnson, the doomed Delta blues legend whose generations-old songs still endure; to Prince, a still-maverick talent whose sound embraces everything from funk to ballads to rock.

From Lake Itasca, Minn., to the Gulf of Mexico, the regions bordering the Mississippi are saturated by a myriad of musical forms. But they've all got one thing in common: the body of water whose timeless spirit runs through the music. The regions hard by the Mississippi have for generations been incubators for musical talents whose creative range mirrors the geographic breadth of the river that is their touchstone and inspiration.

Davenport as ‘crossroads’

Memphis, Chicago and New Orleans are reliably linked to the provenance of the American sound, but you're not likely to hear the name of Davenport, Iowa, when the hothouses of American music are mentioned. What makes the town of 98,359 people such a fertile location for study of American music, though, is mostly a matter of being in the proverbial right place and time.

First, there's where it is (bordering the Mississippi) and what it is (Beiderbecke's birthplace, site of major blues and jazz festivals).

One of the newest places to celebrate music inspired by the Mississippi is the River Music Experience Museum, which opened in Davenport in June. Connie Gibbons, the museum's executive director, says the fans are already lining up. “The first people are typically the ‘choir’ — it's the converted, consumers and fans of the music,” she said. “We're fortunate because with river music you're talking about blues and jazz, country and rock, and we cover a wide spectrum of genres. We're able to draw from supporters of all those types.

"As word spreads, you get people coming in that are curious about it,” Gibbons said. “There's a real fascination with the river's history and lore. With this particular center and the music, it's all a vital part of the American experience, and music tells that story like no other medium can.”

Davenport is a literal intersection of creative possibilities. “It's a crossroads,” said Gibbons, who moved to Davenport from Texas in early 2003. “There’s always been a large group of people here who are consumers of music. Several festivals are popular here.

“As musicians travel across the country, it's been a natural stopping point for musicians to stop and share what they're doing. As such it's a natural site for this museum. The community itself is undergoing a renasissance. There's a major art museum opening within a year. There are a lot of things going on that encompass the business element and the art, and it really represents a true renaissance.”

Gibbons said the overall impact of the river on the sound of America is profound and enduring.

“American music would be much different if not for those communities and artists going on,” she said. “It's everything from New Orleans jazz and the Delta blues, Memphis with rockabilly and rock, and other vital communities like St. Louis and Miles Davis and all the way to the Twin Cities with Prince. It covers such an incredible range.”

Northern latitudes

For years the region of the northern Mississippi — Minnesota to Illinois — has been a veritable hothouse of musical talent. Perhaps the region's most celebrated star, one Robert Allen Zimmerman, was born in Duluth, Minn., and raised in nearby Hibbing. As a boy he was fascinated with folk and blues music; according to the Hibbing Area Chamber of Commerce, Zimmerman's career started early, with some of his first public performances singing for his family at the tender age of 4.

He began playing the guitar in junior high school, forming several local bands. After high school, he moved to Minneapolis for courses at the University of Minnesota, but in 1960 Zimmerman dropped out and moved to New York, beginning a recording career with his first album in 1962, a record bearing his new name: Bob Dylan.

Minnesota's Twin Cities — Minneapolis and St. Paul — are separated by the Mississippi but joined by their status as a creative spawning ground.

Husker Du and Things Fall Down were part of the burgeoning punk scene in Minneapolis in the early ’80s; the Replacements, a band with a fidelity to rock's more dissolute traditions, also hailed from the Twin Cities area, as well as alternative-rockers Soul Asylum, which went from garage band to multiplatinum-selling artists in the early ’90s.

And then there's that Minneapolis native, one Prince Rogers Nelson, the polymath who's made a career of morphing funk, rock, soul and R&B into a musicology all his own. Prince, a Minneapolis native, has made the Twin Cities area a source of his inspiration (and income). He records at his own Paisley Park Studios, which was relocated from Minneapolis to nearby Chanhassen, about 15 miles southwest of the river.

Heartland rhythms

The river was witness to the early lives of musicians from the American heartland. Jazz titan Miles Davis was raised a dentist's son in East St. Louis, Ill.; Chuck Berry, perhaps rock's first great songwriter, was born in St. Louis, Mo.

John Hartford, the singer-songwriter whose thoughtful ballads and story-songs formed a bluegrass counterpoint to the edginess of ’60s rock, was a transplant — born in New York — but grew up near the river, in St. Louis. Hartford, who got his first job on a riverboat, performed with bluegrass bands in Missouri and Illinois. His musical versatility made him popular; his country-pop standard “Gentle on My Mind” was recorded by stars from Glen Campbell (it was one of his first big hits) to Aretha Franklin.

Hartford, who died in June 2001, recorded with artists from Vassar Clements to the Byrds, and moved across the country from Nashville to Los Angeles. But Hartford never lost his love for the river, its music or its personalities; one of his later, Grammy-winning albums, "Mark Twang," combined his original style with traditional folk and bluegrass, music indigenous to the region near the river that sustained him.

Soul and Stax

Soul music, that staple sound of the ’60s, was nurtured by the river, perhaps nowhere better than at Stax Records, a small but fiercely inventive record label born in Memphis.

The company, founded in 1959, hit its stride in the mid- to late ’60s with hits from Joe Tex, Rufus Thomas, Albert King, Booker T. & the M.G.'s, Sam & Dave, Isaac Hayes and the incomparable Otis Redding.

After many changes in musical tastes and reversals of financial fortune in its later years, Stax went bankrupt in late 1975, though recordings under the Stax name have been licensed for release in the years since.

But Memphis never forgot Stax. In May 2003 the Stax Museum of American Soul Music was opened at 926 East McLemore Ave., — a 17,000-square-foot facility built on the site of the old Stax studios, containing more than 2,000 artifacts and exhibits and a film library.

For Deanie Parker, museum president and executive director, the Mississippi River's presence opened the door to “a cross-pollination of music and expressions of ideas,” one she says continues today.

“It's very important to understand not only what was captured in the walls of that building at 926 East McLemore,” she said. “Some of the rap artists and the songs they sample verify that the music they created at Stax Records is timeless. It's still influencing the musical styles and tastes of musicians, artists, writers and producers today.”

‘A part of your flesh’

For Parker, who worked at Stax as a teenager in the ’60s, the music’s never vacated her life; its presence, like the river that borders her city and runs through her country, remains something indelible.

“I heard Albert King guitar lines and Steve Cropper and horn riffs by Otis Redding and the Memphis Horns,” she said, “and I heard the stylings of Isaac Hayes and David Porter.... When you grow up in the environment where that was created, it becomes a part of your flesh, of your very being. That's the way that music is with me.”

“I worked there from 1961 to 1975, doing almost anything there was to do there that was legal,” Parker said of her own soulful résumé. She tried to be a recording artist but eventually found other opportunities in the administrative side. She helped start the label's first publicity department, dabbled in promotion and artist relations, and even sang occasional supporting vocals.

“I backed up Carla Thomas!” she said with a pride you hear through the phone.

The hothouse on East McLemore

“At the time I was at Stax, we were in our own little world within a very hostile city,” Parker said of her time in the hothouse on East McLemore. “The organization was totally integrated among the executive staff — ownership, the creative team, musicians and artists from top to bottom,” she said. “We were enjoying the privilege of working together....

“No idea was ever suppressed,” she said. “We were all encouraged to think out of the box. It became a natural way of thinking or behaving. We pushed that to the limit, and that's what was so exhilarating about it.”

But it was no panacea. “All this was going on amid bigger things throughout the nation,” Parker said. One of those bigger things occurred on April 4, 1968 — the day the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at the city's Lorraine Hotel, about two miles from the Stax studios. Outside her soulful oasis, she noted, “the difference was as night is to day.”

Down in the Delta

The southern Mississippi is midwife to different musical styles, from gospel to jazz to zydeco and more. But at first blush, the culture indigenous to the river brings to mind one music. Say “Mississippi,” and “the blues” might as well be in the next breath. That music and life in the fertile Mississippi Delta are so inextricably intertwined, some might say there's no difference between them, certainly not to fans of American music.

The blues is as much process as event. That process began with the field hollers and work songs of slaves before the Civil War, continued on the plantations of the Mississippi Delta at the end of the 19th century. Its presence was more formally discovered in 1903, when bandleader W.C. Handy heard an itinerant guitar player on a train station platform in Tutwiler, Miss. Handy's “Memphis Blues,” published in 1912, legitimized the blues as an indelible cultural force.

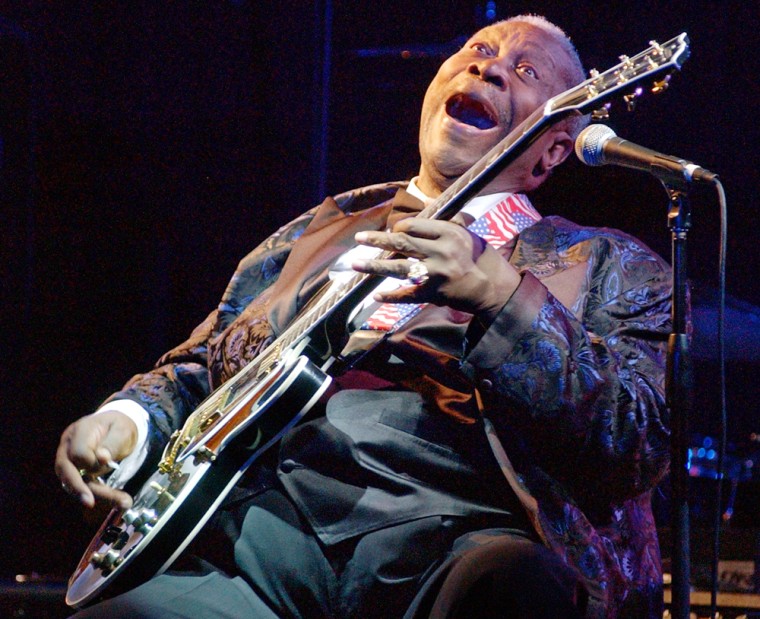

Some of the blues' early practitioners — Mississippi John Hurt; Son House; the prolific, mysterious, peripatetic Robert Johnson; and B.B. King — were natives of the Delta region. Others moved there later in life; Mississippi Fred McDowell adopted the state as a residence and part of his professional name; Robert Jr. Lockwood, born in Arkansas, learned to play guitar from Robert Johnson in the heart of the Delta.

Mississippi Delta blues continues today, an art form whose emotional resilience tells the story of America — despite the fact that, with the relative absence of blues sales, America isn't listening.

"Blues is an unsentimental music,” said Stanley Crouch, the author, essayist and jazz musician. “It's a music of great sentiment, but it's unsentimental. That separates it from R&B, which has a quality of sentimentality. It definitely separates it from rock, which has a hysterical sentimentality, or from rap, which is a testament to the decline of music education in the public schools.”

“Blues is a lot of things: It's a sedative, a form of exorcism,” Crouch told MSNBC.com in a 2003 interview. “One achieves freedom from the blues by confronting the blues. If you can express it with a certain level of emotional and musical eloquence, you will be somewhat liberated from the thing that's hounding you.”

The hold on the soul

Like blues music, the Mississippi River's impact on some American cities runs deeper than for others; for the city of New Orleans, for example, the river called the American Nile has been an especially powerful spiritual aquifer, for generations nourishing the cultural life of the city many hold to be the literal birthplace of jazz.

And observing its impact on one of the city's favorite sons — Louis Armstrong — Douglas Brinkley, the author, historian and director of the New Orleans-based Eisenhower Center for American Studies, seemed to grasp the river’s place in the national imagination, its hold on the soul.

“Armstrong, at age 14, used to play his cornet as an orphan along the river, and his first real gigs were playing on the riverboats for money,” Brinkley said.

“Here’s one of the great jazz musicians — just like the Marsalis family of New Orleans and so many others — who have this deep historical bond to the river. Their art and their lives are really intertwined with it.”