In the midst of a hotly contested presidential election, the U.S. Supreme Court has handed President Bush a historic defeat in the cases of Yaser Hamdi, an American citizen captured in Afghanistan but now being held in the Navy brig in Charleston, S.C., and alleged al-Qaida and Taliban personnel held at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay in Cuba.

With its decisions in the two cases and that of another American citizen and alleged al-Qaida member, Jose Padilla, the Supreme Court has opened the way to much more legal battling.

And the justices have added to Bush’s difficulties at a time when opinion polls show him in an atypically weak position for a wartime leader seeking a second term.

The Guantanamo prisoners, who won a major victory in the court’s ruling in Rasul v. Bush, will now be free use the federal courts as a forum to make their cases not only to federal judges but perhaps to the wider world as well.

The decision made history: For the first time, alleged enemy fighters will be able to use American courts to seek a writ of habeas corpus to challenge the reasons for their capture.

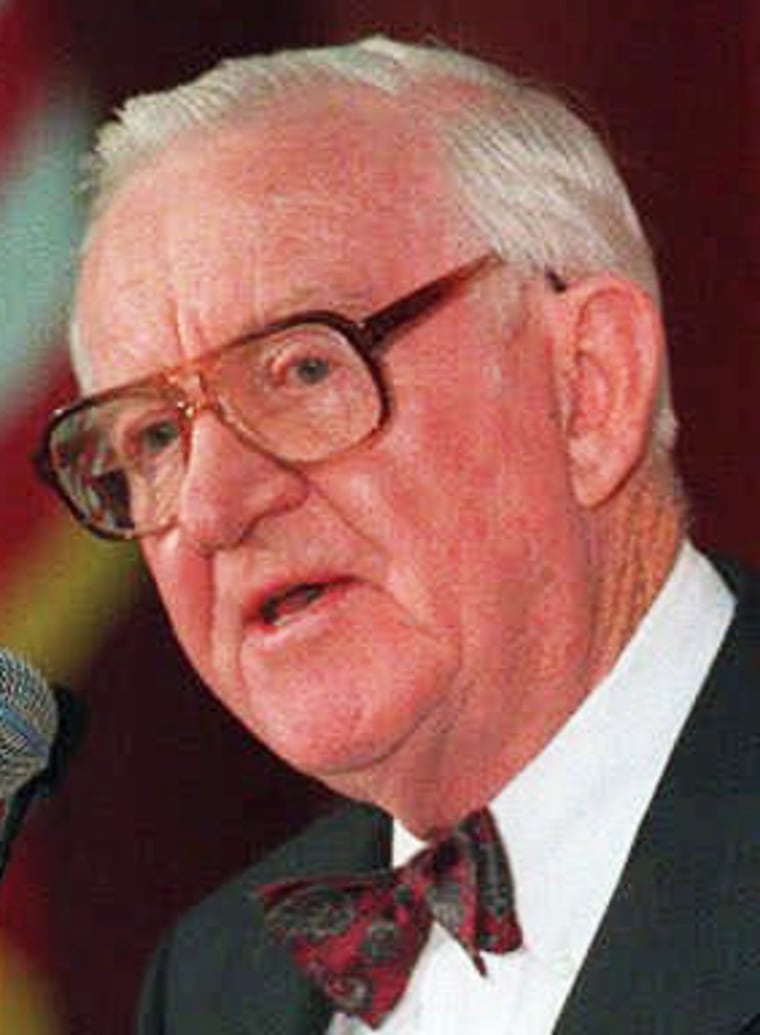

An opinion written by Justice John Paul Stevens, joined by four other justices, declared that “the federal courts have jurisdiction to determine the legality of the Executive’s potentially indefinite detention of individuals who claim to be wholly innocent of wrongdoing.”

Justice Anthony Kennedy concurred in the decision but used different reasoning than Stevens and the others.

Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent in the Guantanamo case warned of dire consequences: "From this point forward, federal courts will entertain petitions from these prisoners, and others like them around the world, challenging actions and events far away, and forcing the courts to oversee one aspect of the Executive’s conduct of a foreign war."

But the American Civil Liberties Union celebrated the outcome in all three cases: "Today's historic rulings are a strong repudiation of the administration’s argument that its actions in the war on terrorism are beyond the rule of law and unreviewable by American courts," said ACLU Legal Director Steven Shapiro.

In the Hamdi decision, six justices held that he must be given some type of a hearing, if not exactly the same one that an American citizen accused of a common crime receives.

Writing for the majority, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor tried to devise a set of rough-and-ready rules in an attempt to guide the district judge when he hears Hamdi’s case.

Some of these suggested rules do not square with what American civilians accused of crime get: for example, hearsay may be accepted, and the presumption may be in favor of the government rather than in favor of the accused.

Adam Charnes, a former law clerk to Justice Kennedy and a former Justice Department official in the Bush administration, saw the Hamdi decision as a partial victory for the administration, even though it had sought to deny Hamdi any hearing at all.

"Five justices squarely rejected the argument that the Executive lacks authority to detain U.S. citizens who are soldiers for our enemy and fight against our military," Charnes said. "The Court held that, if the government establishes that Hamdi was an enemy combatant, he can be detained until the end of hostilities."

He said O'Connor's opinion "can be read as representing a careful balancing that both gives Hamdi a fair opportunity to prove that he was not an enemy soldier and protects the interests of the military in avoiding undue interference with battlefield operations. ... Most critically, O'Connor's opinion also holds that the opportunity to prove that Hamdi was not an enemy combatant may be given to a military tribunal, not a civilian court."

It is still far from clear whether Hamdi, Padilla or any of the Guantanamo detainees will ultimately be able to convince the judges who hear their cases to free them.

Former Reagan Justice Department official Doug Kmiec, who now teaches at Pepperdine University law school, pointed to the raft of new questions raised by the court's Guantanamo ruling.

The majority declared the detainees had a right but, asked Kmiec, "the right to do what? Go to which district court, since Congress has not created any with jurisdiction over Guantanamo? And when the detainees get into that mystery district court, what remedies to vindicate their right of habeas corpus will they be given? Habeas isn't a get-out-of-jail-free card, it is a requirement for justification, but at what level? All is left far too casually undefined by Justice Stevens for me."

Heading into battle

The defeats suffered by the Bush administration Monday force Justice Department lawyers into battle on several fronts, as they try to persuade judges that these men truly are too dangerous to be set free in time of war.

Even in the one case that it ostensibly won, that of Padilla, the administration gained a only temporary halt in his effort to find a federal court in which to make his claim of innocence.

Especially significant in this election year in which control of White House, the House and the Senate are all at stake, the court’s rulings could increase the pressure on Congress to legislate some rules for handling enemy combatants, especially the ones at Guantanamo.

Will the Republican congressional leadership now seek a vote on a bill to detain enemy combatants? And how would Democratic presidential nominee Sen. John Kerry vote on such a bill?

Scalia's vehement dissents in both the Hamdi and Rasul cases amount to a powerful appeal to Congress to act.

Declaring that the Rasul decision “has a potentially harmful effect upon the Nation’s conduct of a war,” Scalia noted, “Congress is in session. If it wished to change federal judges’ habeas jurisdiction from what this Court had previously held that to be, it could have done so.”

So too in his Hamdi dissent, Scalia said, “It is far beyond my competence, or the Court’s competence” to figure out precise, detailed rules for how to handle the long-term detention of enemy combatants.

“But it is not beyond Congress’s (competence),” Scalia said. “If the situation demands it, the Executive can ask Congress to authorize suspension of the writ (of habeas corpus) — which can be made subject to whatever conditions Congress deems appropriate.”

'Openly and democratically'

The only proper way to limit the civil rights of American citizens accused of aiding the enemy, he said, is to do it “openly and democratically, as the Constitution requires, rather than by silent erosion through an opinion of this Court.”

The litigation now unleashed may well have propaganda value both for the administration and for its adversaries.

The Guantanamo detainees will use federal courts to try to win their freedom — this may well lead to further appeals and bring the lawyers and the reporters back to the Supreme Court as specific cases are decided by lower courts

And, in this election year, the stage is now set for the president to go to Congress and the American people and, in effect, say, "Give us the war-time tools we need to fight terrorism and keep dangerous people locked up."