One of its nicknames inspires confidence that it can handle it all. The thousands of barges and recreational boaters plying its waters day in and day out. The tons of fertilizers and other runoff from farms and cities. And the nearly 500 species of wildlife that call it, and the banks that embrace it, home.

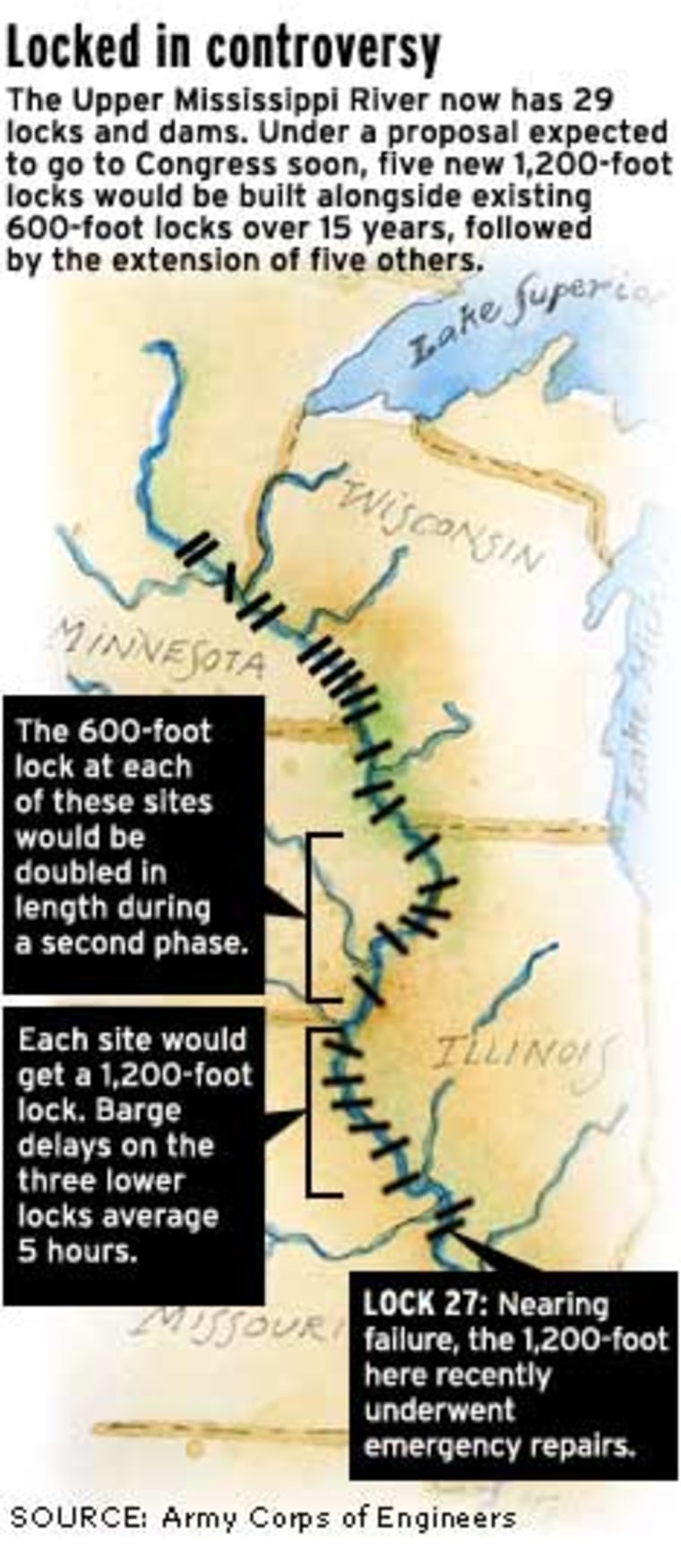

Yet might the Mighty Mississippi be near the breaking point? That's what environmentalists fear for its ecosystem. Farmers and barge operators fear it's crumbling for another reason: a 70-year-old system of locks that's too small for today's 1,200-foot-long barge tows. Those 29 locks act as staircases as the river drops 350 feet between Minneapolis and St. Louis.

The U.S. government, for its part, has long claimed that the Mississippi can handle it all. In fact, the Upper Mississippi — where the debate is strongest — is the only river designated by Congress as both a nationally significant transportation network and a nationally significant ecosystem.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the agency that manages how the river is used, had been criticized for not doing more to balance both needs. But in the last few years it's taken the advice of scientists and adopted a "holistic" approach to decisions as it makes a case for $2.4 billion in transportation improvements and $5.3 billion for ecosystem restoration from St. Paul to St. Louis.

What's proposed

Those numbers cover a 50-year period and, if approved, would represent the most expensive navigation project in U.S. history. The environmental funds represent five times what the U.S. government now spends on the ecosystem.

After a 10-year, $70 million study, the Corps advised spending:

- $1.7 billlion to build five new locks over 15 years alongside existing but shorter ones. If all went well, that would be followed by doubling the length of five existing locks at a cost of $700 million.

- $1.5 billion would be spent over 15 years to restore islands and floodplains, build fish ladders and protect shorelines. After that time, $3.8 billion would go to similar work.

The new locks would be 1,200 feet long, the length needed to avoid having to decouple barge tows -- a process that costs time and money.

All but three of the Upper Mississippi's locks are 600 feet long, and the new locks would be built where the delays are longest, an area where some locks average 5 hour delays.

Half the locks money would come from a barge tax, the other half from general U.S. funds. All of the environmental funds would come from the U.S. government.

Those in favor

Farmers and barge operators, who use the river to move 60 percent of the nation's corn exports and 45 percent of its soybean crops, say the delays at locks are making it harder to compete with other nations.

They also say 400,000 jobs are tied to the river, and that congestion has cost 30,000 jobs and led to $560 million less in annual revenue for the region.

And they have what they feel is an environmental ace in the hole: the fact that moving grain by barge is much less polluting than by truck or rail.

"You can't just be a river environmentalist, you have to take the entire ecosystem into account," says Paul Rohde, vice president of the Midwest Area River Coalition 2000, a river users group.

The Corps agrees, with spokesman Alan Dooley noting that "a single 15-barge tow carries the equivalent of 870 53-foot semitrucks (and) as much as 225 rail cars."

As a result, he adds, "a gallon of diesel fuel moves a ton of cargo 60 miles on a highway, 200 miles by rail and 600 miles on a barge."

Rohde notes barges alleviate traffic as well. "I don't think anybody would say they'd rather have 800 trucks in their city than one tow going quietly down the Mississippi," he says.

Those against

Environmentalists, for their part, certainly don't favor new or expanded locks. American Rivers, a conservation group, put the Mississippi back on its list of most endangered rivers because of the proposal.

Instead of new locks, they say, river users should adopt a scheduling system akin to an airport, where barges would have set times to use the locks. The Corps has promised to test the idea, but Rohde doesn't think it's practical and compares it to forcing a city's residents to split their commute hours.

While solidly in favor of scheduling, environmentalists have taken slightly different approaches on the locks issue.

Scott Faber, an expert with Environmental Defense, is flat out against any compromise. "Barge movements harm the Mississippi by pushing sediment into backwaters, by uprooting aquatic plants, by eroding banks, and by killing millions of fish," he says, noting that the Corps estimates the locks work would increase sedimentation at 31 sites, degrade 27 miles of plant beds, increase erosion on 11 miles of shoreline and result in a decline of 28 million fish.

On the other hand, Dan McGuinness, director of the Audubon Society's river program, is more amenable, noting that most of the damage to the river was done when the locks first went in. But his group is also seeking $3 billion more for restoration. "If Congress authorizes and appropriates funds for a 50-year, $8.4 billion ecosystem restoration program," he says, "it will be a net gain for the river regardless of what decision they make on the locks."

Still, both groups are mistrustful of both Congress and the Corps. "Audubon is concerned that if funds are tight, Congress will spend money needlessly on lock expansion and then not fund ecosystem restoration," says McGuinness. "That would be the worst case scenario in our opinion."

Faber worries that the Corps, which was caught cooking the books in 2001, will do the same when it comes to restoration. "This debate is a referendum on whether the Army Corps, the river's primary manager, will be permitted to cheat," he says. "Will the Corps use junk science to determine the future of America's greatest river? That's what is at stake here."

"About 40 species have already gone extinct (along the river), 10 species are on the verge and many other speices are declining," he adds.

Congress to decide

Both sides have been lobbying Congress, which will have the final say over the Corps' recommendations.

Bipartisan legislation has been advancing in the Senate, and a decision could be made before or soon after the November presidential elections.

Right now the wind is favoring the Corps' proposals. Environmentalists often have Democrats as allies, but on this issue some Democrats from the river area are touting the legislation as a win-win deal.

"There will be uncertainty" on funding environmental projects after 15 years, Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., acknowledged last month. "But I say to the environmental groups that ... there's just no better arrangement, and they should view this as a great opportunity."

Scientists: Stay flexible

A National Academy of Sciences panel has also weighed in on the Corps' proposal, in a recent report welcoming the "more holistic approach" that recognizes both nature and navigation.

But the panel cricitized the Corps for not doing more to study other options to alleviate barge traffic. "Scheduling systems, systems of tradable arrival slots, or a contingent fee — as challenging as their implementation may be — could be implemented instead of extending locks or could be used in combination with lock extensions," the panel wrote.

The panel urged the Corps to implement such changes if they prove feasible, and more recently it urged that aboveall the agency become more flexible — ready to modify policies if conditions change.

"The ecological conditions of the river system will continue to change, scientific knowledge of the system will evolve and improve, and there are likely to be shifts in social preferences" on how the river is used, panel chairman John Boland told a House water resources subcommittee last June.

"Given this variety of unknowns," the professor emeritus of geography and environmental engineering at Johns Hopkins University added, the decisions made "should aim to be as flexible as practicable."