Gordon Bethune had inherited a mess. When he took the job of CEO of Continental Airlines in 1994, he was making the decision to commandeer a company that was losing nearly $55 million per month. The fifth-largest U.S. airline had way too many planes flying unprofitable routes. Its on-time performance consistently ranked last among the top 10 airlines, costing an average of $6 million per month in added expenses for misconnected bags, hotels, overtime and lost revenue due to canceled flights. Continental also ranked dead last in service, customer complaints and mishandled baggage. It was on the verge of declaring bankruptcy for the third time in 10 years.

By most accounts, Bethune engineered one of the most dramatic corporate turnarounds in history, largely by unlocking the value of Continental's 45,000 employees, whose input had been shunned by what he referred to as "cloistered management."

"Poor operations were and are the result of poor morale in work force and management," Bethune says. "I had to get people focused on the single goal of getting the airline functioning on time. I had to get employees to believe what I said.

"After two bankruptcies, it was like dealing with abused children--they simply don't believe you," he adds. "To them, I was just another guy in an Italian suit."

Bethune's predecessor, Robert R. Ferguson III, reportedly had been forced out after three and a half years at the helm. Bloomberg Businessweek articles around that time referred to him as a "blunt and often prickly" CEO, who "seemed aloof to the rank and file and was known to publicly humiliate managers."

Bethune was pretty much the opposite. A onetime Navy aircraft maintenance officer, he had come up through the ranks of the industry and enjoyed constant interaction with Continental employees. "You can't treat your employees like serfs," he says. "You have to value them. I know if I piss off a mechanic, he's gonna take twice as long to fix something. That's Human Nature 101. If employees are hostile, they'll go out of their way to screw you."

Gordon Belhune Photo courtesy of Gordon Belhune

He started offering bonus money to every Continental employee for each month the airline showed on-time performance in the top five of the 10 airlines measured by the Department of Transportation. He also began a profit-sharing plan--once there were profits to be shared.

By 1995, Continental ranked first in on-time performance among major airlines. Posting its first profit in 10 years, the company earned record income for 11 straight quarters, upping its share price from $3.25 to more than $50. High rankings in customer and employee satisfaction followed.

"I started giving everyone extra money, and made their lives better," Bethune recalls. "We could afford it because we'd been paying even more money for disaffected employees.

"We got the managers, the customers and the employees in the same boat--everyone wins, or no one does," he adds. "It's like football. Before each play, there's a huddle. Who do they let in the huddle? Everybody on the team, not just the big shots in the backfield. Because everybody needs to know the plan, and that's how we operated the company."

Bethune retired in 2004, but his style and substance have made him a legend in the airline industry. They also make him a poster boy for the notion that good leadership has a demonstrable effect on a company's bottom line.

Leadership Quantified

Can it be proved that good leadership increases profit? Over more than 30 years, Gallup has conducted research involving more than 17 million employees on the degree to which they are emotionally committed to their company's goals. Among the findings:

- "Engaged" employees are more productive, more profitable and more customer-focused.

- "Actively disengaged" employees erode an organization's bottom line, to the tune of more than $300 billion annually in the U.S. alone.

- Companies that actively engage employees in their operations have 3.9 times the EPS growth rate, compared with organizations in the same industry with lower engagement.

"I've done plenty of research on the different ways organizations are run, and how you engage people in contributing to their success," says Bill Pasmore, senior vice president at the Center for Creative Leadership. "I've found that leaders who make choices to operate in a more participatory way--who operate on principles of high engagement, vs. bureaucracies that treat people as if they were cogs in a machine--see a 30 percent improvement in performance."

In their 2009 report "How Extraordinary Leaders Double Profits," Jack Zenger, Joe Folkman and Scott K. Edinger cite a study they conducted for a Fortune 500 commercial bank. After a lengthy assessment, they divided the bank's leaders into the best 10 percent and the worst 10 percent, finding that:

- More than 50 percent of employees who thought about quitting reported to leaders in the bottom 10 percent. Slightly more than 15 percent who thought about quitting reported to the top 10 percent.

- The worst leaders' departments experienced average annual net losses of $1.2 million, while those of the best leaders netted profit of nearly $4.5 million.

- About 37 percent of employees led by the bottom 10 percent said they were satisfied with their pay. Nearly 60 percent who said they were satisfied with their pay were led by the top 10 percent.

The happier employees weren't necessarily being paid more by leaders in the top 10 percent, Zenger, Folkman and Edinger write: "They are in reality often living proof of the old saying, 'You can't pay me enough to work for that person.'"

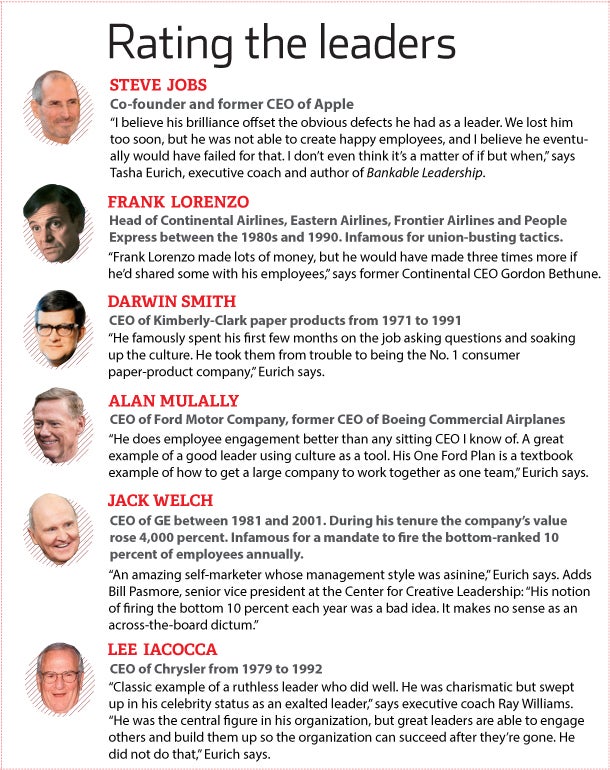

Good leadership has an undeniable business value, confirms Tasha Eurich, a psychologist, Fortune 500 executive coach and author of the 2013 book Bankable Leadership: Happy People, Bottom-Line Results, and the Power to Deliver Both.

"Good leaders create prosperity, and it's not defined just by money, but by the emotional health of their employees. Good leaders treat employees as humans and appreciate them by creating an environment people want to be in," Eurich says. "Good leadership creates happy employees, who create happy customers and, ultimately, happy shareholders."

Flying high: Gordon Bethune took over Continental Airlines in 1994; the following year the airline ranked first in on-time performance and posted its first profit in 10 years. Photo courtesy of Gordon Belhune The Right (and wrong) Style

What style of leadership is best for engagement? Robert Hogan, a psychologist and global authority on leadership and organizational effectiveness, surveyed more than 1,000 employees about the personalities of their best and worst bosses. He found that manager personality is a valuable predictor of employee engagement. Managers who tended to be calm, business-focused, organized and willing to listen were three times as likely to have highly engaged work groups, compared to managers described as manipulative, arrogant, distractible and overly attention-seeking.

"Arrogant bosses tend to blame their mistakes on others, overestimate their competence and lack a sense of team loyalty," Hogan writes in his study. "Manipulative managers often ignore commitments, bend the rules and disregard others' concerns. These tendencies undermine manager-employee trust and can damage engagement."

In Bankable Leadership, Eurich outlines two archetypes, one at each end of the spectrum, both equally ineffective.

First, there's the "cool parent," who focuses on the team's happiness at all costs. "They don't set expectations, give honest feedback or make tough decisions," she says. "It might feel pleasant at first, but as soon as you need tough-but-true feedback, he or she would freeze like a deer in headlights."

Then there's the "trail of dead bodies" type of boss. "This leader requires grueling hours, is never satisfied and withholds recognition," Eurich says. Leaders of this type may help you "up your game" initially, she explains, but in the long term, they drive results so aggressively that you suffer both physically from overwork and mentally from lack of appreciation.

The "bankable" leader is able to move to the middle, Eurich contends, understanding and caring for team members while setting aggressive performance targets. "Think of the best manager you've ever had," she says. "He or she might have been a walking contradiction. They provide recognition and push for continuous achievement. They help you succeed and accept responsibility for your successes and failures."

But beware of any one-size-fits-all approach, says Barbara Kellerman, a lecturer in public leadership at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government. The solutions for effective leadership at a 20-person plumbing-supply company will be wildly different than those for a multibillion-dollar tech company. Kellerman, who has written more than 15 books on leadership, also throws cold water on the notion that any corporate knight in shining armor is likely to save the day. "The longer I'm in the field--the 'leadership industry' I call it--the less I'm persuaded to talk about a leader as some saintly, amazing person," she says. "It's perfectly idiotic."

Executive coach Ray Williams, a columnist for Psychology Today, contends that our image of a good business leader has become dysfunctional. He even goes so far as to say there's an increase in psychopaths in the business leadership class.

"If you take away the violent tendencies that are the most disturbing hallmark of the psychopath, I find many of the other symptoms in the boardroom today," he says. "The extreme narcissism, the charm, the aggressiveness, the lack of conscience. These are seen as valued traits in a leader today."

The need to be in the limelight, for celebrity status, to take credit for the work of others, to blame others when things go wrong--these personality traits are typical of psychopaths, Williams adds. "When companies recruit leaders, they tend to value highly people who are ruthless, who can make tough decisions--that sometimes can be hurtful to thousands of people--and not lose any sleep over it."

Pasmore takes a similar stance. "Poor leaders develop a culture of arrogance and protection. They think they can do no wrong, and they hire yes men who think the way they do. They believe they were hired because they had all the answers," he says. "That belief causes most of the problems we see in organizational performance."

New Metrics

Williams thinks one executive hiring trend may trump the bad behavior so evident in the corner office--the slow, steady emergence of women in the executive suite.

"You rarely find a psycho who's a female," he points out. "The more we balance the scale and have feminine leaders, the better off we'll be."

Female decision-makers, Williams says, "tend to be more collaborators and peacemakers. I think in modern times we need more leaders like that, instead of the win/lose, cutthroat approach of annihilating the competition. I don't think the world of business has been well-served by that model."

He cites consulting group Catalyst's groundbreaking 2004 report "The Bottom Line: Connecting Corporate Performance and Gender Diversity." It concluded that businesses with the most gender diversity at the top had, on average, 35 percent better return on equity and 34 percent better total return to shareholders than those with the least gender diversity at the top.

Clearly, those in leadership positions at public companies face enormous, often insurmountable pressure to show quarterly improvement. Yet some leadership experts bemoan what Williams calls "short term-ism," and all the important factors it ignores.

Harvard's Kellerman believes business leaders should be judged by measures other than market performance. "Is the company socially aware? Does it pollute? Is it riddled with greed? Does it take care of its employees? Is it charitable-minded?" Kellerman asks. "It's reasonable to invoke those measures when evaluating leaders."

Indeed, there's a much bigger definition of good leadership that we discount. "Snap judgments are getting shorter all the time," Williams contends. "There was a time when companies could have long-range plans."

It should be fair to ask of a leader what kind of impact his or her company has on the welfare of the community, Williams adds: "Great financial results need not be at odds with making a significant contribution to the community and the environment."