Worms anchored to the skeleton of a young gray whale in a watery canyon off the coast of California are the first known whalebone-eating marine worms.

At this all-you-can-eat whalebone buffet, female marine worms never leave once they dig in. Males never visit the buffet — they live inside the females. Bacteria within the females’ roots help the worms eat whalebone fats. A study describing the two new species of worms appears in Friday's issue of the journal Science, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the nonprofit science society.

The worms are the latest discovery in a branch of biology focused on the life that springs up on sunken whale carcasses. These carcasses — “whale falls,” in science-speak — dot the ocean floor and sustain colorful and mysterious oases of life, according to Science author Robert Vrijenhoek, a researcher from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in Moss Landing, Calif.

Bone-eating worms may play important roles in nutrient cycling. A dead whale is roughly equivalent, in food content, to thousands of years of life-sustaining carbon particles that slowly fall to the ocean floor as “marine snow.”

Worms with roots and ‘feathers’

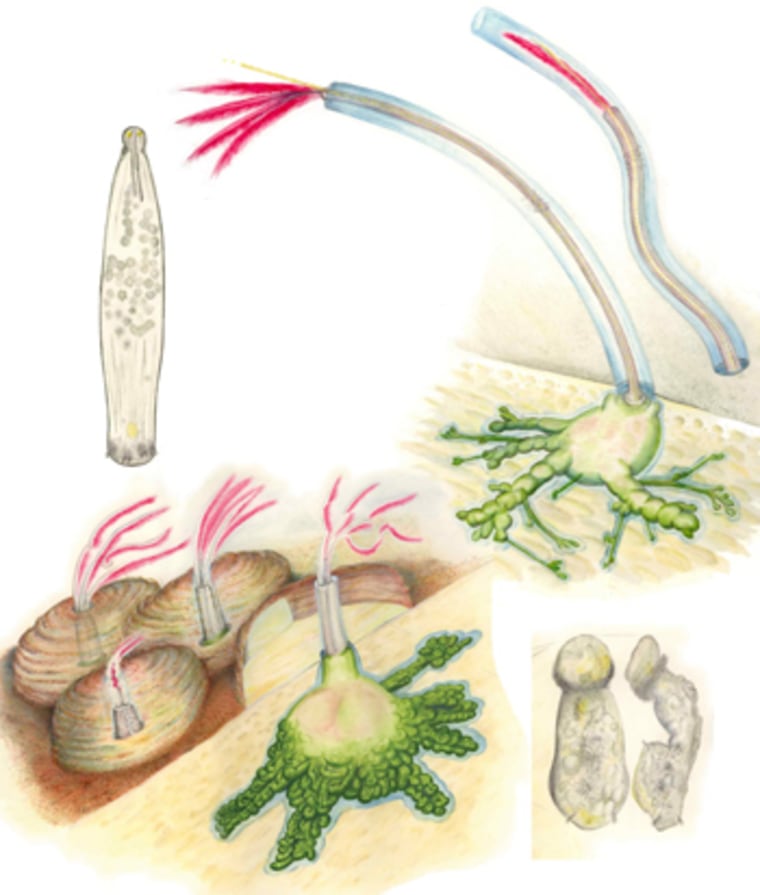

The largest female tubeworms the scientists recovered are about as long as your index finger and as thick as a pencil. They have an outer tube, an inner muscular trunk, an egg-carrying oviduct and plenty of space to house the males. A large egg sac embedded in the bone is sheathed in bacteria-filled tissue that grows farther into the dead bone, like the roots of a plant.

The roots provide lots of bone-front access, or surface area, for the bacteria, according to author Shana Goffredi from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

The bacteria in the roots help digest the fats in the bones and transfer the nutrients to the worms. How the bacteria and worms communicate and transport food back and forth remains a mystery.

The worms are topped with red or red-and-white striped feathery structures called “palps.” Hemoglobin in the palps provides the red color and captures oxygen for both the worms and the bacteria living inside them.

The worms are distantly related to the large tubeworms found at deep-sea hydrothermal vents and cold seeps. “Vent” and “seep” worms also rely on symbiotic bacteria to extract nutrients from their environments.

Striking worm gold

The scientists discovered the whale carcass while searching for clams in Monterey Bay. When the radar screen in the submersible vessel lit up, Vrijenhoek guessed they’d run into a 55-gallon drum someone kicked off a ship.

Instead of trash, their remote-control vessel beamed images of brilliant, blood-red patches of worms covering the exposed jaw, skull and ribs of a young gray whale’s carcass. Tissues, fins and organs still clung to the skeleton.

![[#Beginning of Shooting Data Section] Nikon CoolPix995 2003/08/07 18:43:38 JPEG (8-bit) Fine Image Size: 2048 x 1536 Color ConverterLens: None Focal Length: 11.7mm Exposure Mode: Manual Metering Mode: Multi-Pattern 1/500 sec - f/3 Exposure Comp.: 0 EV Sensitivity: ISO 100 White Balance: Preset AF Mode: AF-C Tone Comp: Auto Flash Sync Mode: Front Curtain Electric Zoom Ratio: 1.00 Saturation comp: 0 Sharpening: Auto Noise Reduction: OFF [#End of Shooting Data Section]](https://media-cldnry.s-nbcnews.com/image/upload/t_fit-760w,f_auto,q_auto:best/msnbc/Components/Photos/040729/roboworm.jpg)

The whale remains probably fell to the bottom of the canyon several months before the scientists discovered the whale. The canyon’s depth protected tissues and organs from scavenging sleeper sharks and swarms of hungry hagfish.

As the scientists aboard the ship directed the vessel’s robotic arm to grab a piece of whale bone, Vrijenhoek suspected that they had encountered a previously known strain of worms.

When he saw the mucosy tubes clinging to the whale bone, however, he knew he’d struck worm gold. In 1995, Vrijenhoek and a team of scientists led by whale fall expert Craig Smith of the University of Hawaii found similar tubes, but no worms. Without whole bodies to dissect or DNA to analyze, they called the unseen creatures that lived inside the tubes “green snot worms.”

Now, he had the tubes plus the worms. Within a week of the worm discovery, the scientists concluded that the DNA from their catch did not match DNA from any known worms. Further analysis placed the worms into two new species, both from the new bone-devouring genus Osedax.

The red and white striped plumes that project from the smaller species, Osedax frankpressi, contrast with the uniformly red plumes of the larger worm species, Osedax rubiplumus.

Dwarf males

Even though the scientists created a genus for the worms which translates as “bone devourers,” only the females eat bones.

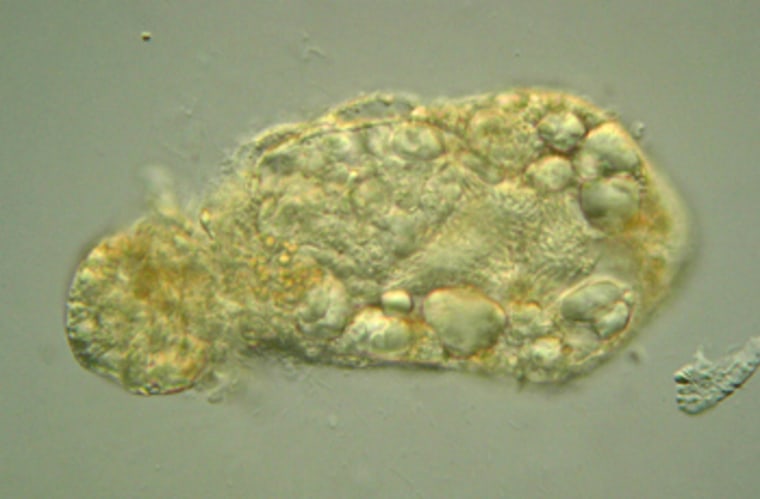

The microscopic, yet sexually mature, males abstain from the whalebone diet. Instead, the dwarf males feed on internal yolk droplets — fatty leftovers of the eggs from which they developed.

Full-grown males haven’t changed much in appearance since their days as larvae — aside from some hairs on their front sides and hooks on their backsides.

The differences between males and females from the same species are among the most extreme in the world.

“If you saw a male, you’d think it’s a larval worm — yet it’s making sperm,” Vrijenhoek said.

This “sexual dimorphism” is especially surprising because the males and females of their sea-vent-dwelling worm relatives are about the same size, according to author Greg Rouse from South Australian Museum and the University of Adelaide in Adelaide, South Australia.

Rouse discovered the microscopic males inside the females after his colleagues mailed him a piece of whalebone covered with the red-tasseled worms.

Sperm cells from packs of males compete to fertilize eggs moving up a tube toward the egg release site at the female’s feathery top. The largest female the scientists studied housed 111 males.

Of the many young worms that find themselves free in the open ocean, only a few land on a dead whale. The scientists hypothesize that worm larvae that land on whalebone develop into females. Larvae landing on female worms develop into males. Worms that don’t land on a mammal carcass or female worm usually die.