In 1952, a very pregnant Joan Hinton resurfaced on the U.S. radar.

The youngest and only female physicist to have helped develop “the gadget” at Los Alamos, Hinton was giving a toast at a peace conference in Beijing.

In her toast, she expressed regret for “helping build a bicycle when I didn’t have control of where it was going to go.”

It was this antiwar appearance that aroused McCarthyist suspicion of her activities in China. Disillusioned by America’s “unnecessary” nuclear attacks on Japan, Churchill’s “terrible iron curtain speech,” and unsuccessful lobbying for civilian control of nuclear energy, she had defected to China four years earlier to join Mao Zedong’s revolution.

'The Atom Spy that Got Away'

“I had wanted to see why millets and rifles beat the Japanese in China,” she said. “And I didn’t want to spend my life killing people.”

Magazines soon emblazoned her trench coat-clad caricature with the title, “The Atom Spy that Got Away,” circulating stories of nuclear espionage.

Hinton, silver-haired and frail at 82, still laughs at the accusations.

She described her homes when she first arrived in China as cave-dwellings that lacked nails, electricity or regular mail service, let alone a nuclear reactor.

Invoking Mao’s famous “paper tiger” epithet for America, she doubts China felt threatened enough to have even begun nuclear research at the time.

Yet, after 56 years in China, Hinton is still quoting Mao. His likeness is ubiquitous in her home, a small apartment on the state-owned dairy farm she’s been running for 20 years.

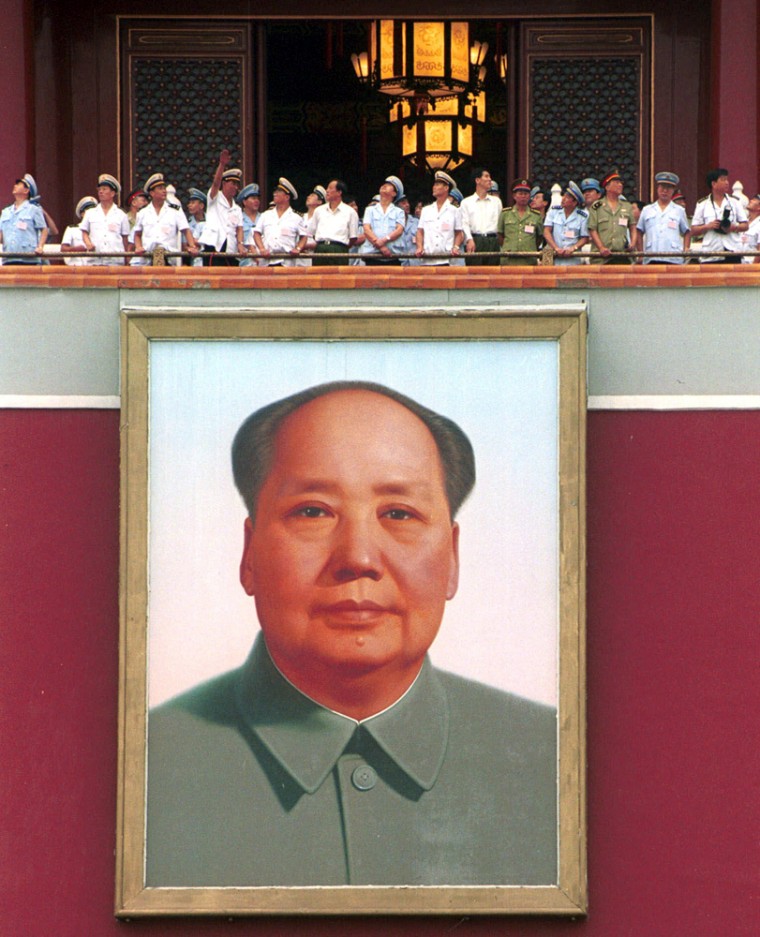

Hinton’s effusive and wistful memories of the “thirty years” under Chairman Mao is rare in China these days. Though his mugshot still beams from the southern wall of the Forbidden City, the government has officially departed from his doctrine, tactfully disowning the more radical movements inaugurated by Mao.

Most of the Mao memorabilia available on the streets of Beijing is consumed by tourists, not Chinese, who have largely outgrown Maoism.

Still a devotee of Mao — all these years later

Hinton is one of his few loyalists. She denounces all of Mao’s successors as “capitalist roaders.” She blasts all of the economic reforms beginning in 1978 and culminating with China’s entry into the World Trade Organization — and its recent bid for market economy status — as betrayals of the socialist cause.

She has few specific policy change requests, but she yearns for the days when everyone “would do the most they could. Everyone developed to their full capacity. Everyone was busy. … Everybody had a job. People weren’t exploiting each other.”

Hinton lauded the Great Leap Forward, the economic development plan from 1958 to 1960, during which a reported 30 million starved to death, as “wonderful” and “exciting.”

“Every time I hear that [statistic], it gets higher. Sure, there were pockets of starvation. … But on the whole it was great. ... You can look around and still see projects started in the Great Leap Forward, like dams and factories,” said Hinton.

“If you don’t threaten people, and they have security, and they know they are developing society,” she said, “people are not lazy.”

Praise for the widely denounced Cultural Revolution

Hinton gushes fervent praise for the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s mass mobilization of Chinese youth to criticize party officials, intellectuals and bourgeois values, from 1966 to 1976. “Mao wanted everybody to take part, to pay attention to national affairs,” said Hinton. “Here they discovered 29 renegades, which was terrific.”

Since Mao’s death in 1976, the party has renounced the Cultural Revolution, recounted in most history books as chaotic and violent. State censors even force domestic publications to lowercase and enclose in quotation marks any allusion to the “so-called ‘cultural revolution.’ ”

Hilton attributed any bloodshed from the Cultural Revolution or Great Leap Forward, and any imprisonment of her friends, to the “capitalist roaders and imperialists,” including Mao's “terrible wife,” Jiang Qing, who was given a suspended death sentence in 1981.

Lenin takes a distant second to Mao in Hinton's eyes, and she has little respect for the North Korean brand of communism.

“They’re not Mao’s communists,” she said, glancing at a muted BBC broadcast on the giant television in her home. “They have this idea that you have to praise the leader. Mao wouldn’t allow roads or places to be named after Central Committee members when he was in power.”

Hinton is even more disdainful of the Chinese leaders who followed Mao. “Deng Xiaoping [Mao’s immediate successor] would rather have just a few people get rich rather than 98 percent of the country getting rich, like under Mao.”

“Today there’s still plenty to do — it’s still a backward country — but people aren’t being mobilized.”

Hinton insisted that there was also more freedom of expression under Mao, at least in the form of weekly “self-criticisms” mandated on a farm she tended.

But, she said, the more she carps about today’s policies, the more today’s party “listens” to her; at last year’s annual meeting of the “foreign experts,” she was seated beside Premier Wen Jiabao.

By contrast, the closest she ever got to a formal introduction to Mao was an anonymous handshake and a stroke of his sleeve.

Content to live out her days in China

Hinton now lives alone with a few admiring housekeepers, about 300 cows and the Internet to keep her company. Her husband, Sid Engst, who came to China in 1946, died last year, and her three children have moved to the United States.

“They probably would have stayed if China were still socialist,” Hinton griped. Hinton herself is still an American citizen, which is “convenient for travel.”

Despite the few model rockets that pepper her desk, a wooden board propped on a pile of bricks that she said most Chinese visitors often poke fun at, she doesn’t keep up with physics. At least not the kind that leaves her looking up at a “terrible purple cloud” in a “sea of light.”

She did, however, design the milking system for the dairy farm, whose produce was once sent to Kraft but is now all domestically consumed.

“In some ways, what I do on the farm is as difficult as my work at Los Alamos,” she said. “There we were all working together. I had other people.”

“And here,” in the People’s Republic of China, “here I’m working alone.”