You can read Civil War books until you’re blue and gray in the face, but it still doesn’t prepare you for the moment when you actually see the killing fields, and the magnitude of the slaughter, bravery and horror hits home. We had such an experience on Day 10 of our Mississippi River journey, as we visited the Vicksburg National Military Park and the Vicksburg National Cemetery.

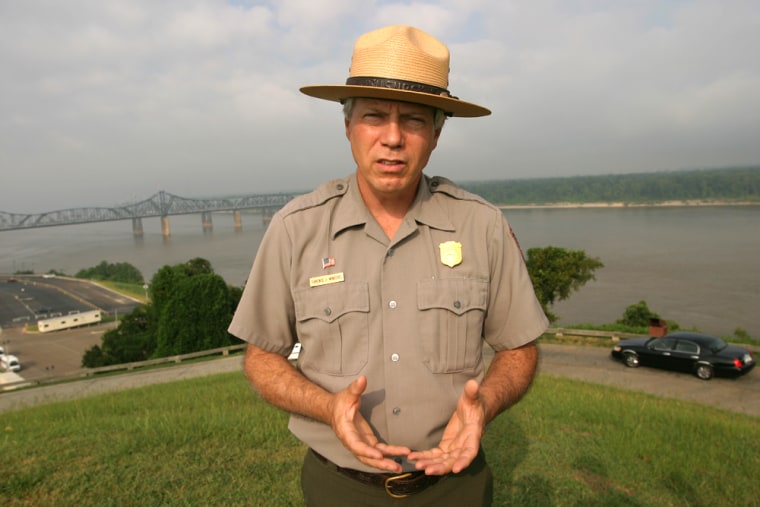

We were fortunate enough to be guided on our journey through our nation’s bloodiest chapter by military park historian Terry Winschel, whose encyclopedic knowledge of the war and Vicksburg’s place in it was instrumental in breathing life into the history.

He had considerable help in evoking the past from the haunting beauty of the 1,800-acre park’s 1,330 monuments to those who participated in the 47-day siege of Vicksburg by Union forces in 1863 and fighting that accompanied it.

Winschel said that American history has been rewritten with the passage of time to put less emphasis on the importance of the Union victory at Vicksburg.

“Today, Gettysburg stands out, because of the greater number of casualties and the Gettysburg address, but in the 1860s Vicksburg was considered more important,” he said.

Winschel said that President Abraham Lincoln himself had identified the city of 5,000 residents as being critical to victory.

“At a meeting of his war advisers early in the conflict, he pointed to a map and told them, ‘See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key! The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket,’” he said.

The Anaconda Plan

As we began our tour of the battleground by visiting a Confederate artillery placement on a ridge overlooking the river, Winschel explained that the heavily fortified city was the Confederacy’s last major stronghold on the Mississippi when Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant set out to capture it in early 1863. Union naval forces already had captured New Orleans and Baton Rouge to the south and Grant’s army was in control of territory to the north.

Control of the Mississippi was critical to the Union strategy known as the Anaconda Plan, which envisioned taking control of the river, thus severing the Southern states from the resource-rich states to the west of the river and then slowly strangling the rebellion.

But Vicksburg, with its heavy artillery overlooking a sharp bend in the river and its heavily defended fortifications, presented the Union with a tough nut to crack.

Grant already had made several attempts to directly attack the city and had spent months on an ill-fated attempt to dig a canal that would reroute the river and isolate Vicksburg when he decided to besiege the city. He had a significant numerical advantage, with 80,000 men pitted against about 30,000 rebels.

Grant’s plan was to harass the rebels inside the city, under the command of Confederate Gen. John Pemberton, while making sure that no supplies made it past his lines. He also engaged in an early form of bio-warfare by dumping rotting animal carcasses into a stream that provided the city with drinking water, Winschel said.

Conditions in the city were described as abysmal. In their book “The Mississippi and the Making of a Nation,” historians Douglas Brinkley and the late Stephen Ambrose wrote that “People endured what no other city on the river had seen. Food supplies were so short that residents were reduced to eating mule meat and pea bread. Medical supplies were almost nonexistent. Water was so scarce that officers posted guards at wells to make sure that none was wasted ‘for purposes of cleanliness.’ The citizens were forced to burrow underground or live in caves to avoid the well-nigh constant shellfire. … They stuck it out. They even printed their newspaper on the blank side of wallpaper.”

Despite the nature of the life-or-death struggle, soldiers on the front lines, often hunkered down within yards of one another behind earthen fortifications, exchanged jokes and discussed politics and philosophy, Brinkley and Ambrose wrote.

“Each army … contained regiments from Missouri,” they said. “One day the pickets at Stockdale Redan (a heavily fortified post) agreed to informal short truces. The area became a meeting place for relatives or friends of the Missouri troops and was called the Trysting Place.”

Such polite exchanges were the exception, however. Grant’s engineers were busy tunneling under the Confederate front lines and planting large caches of explosives under the rebel fortifications. At least one of the subterranean bombs was detonated -- recalling a scene from last year’s movie “Cold Mountain” -- and the Union forces were preparing to set off a series of explosions and mount an all-out attack if necessary to end the standoff.

Pemberton cut rations again and again, trying to hold out until reinforcements could reach the city, but with his forces weakening and taking ill he had no choice but to surrender Vicksburg to Grant on July 4, 1863, giving the Union almost complete control of the Mississippi River (the Confederate garrison at Port Hudson in what is now Louisiana surrendered five days later after learning of Vicksburg's fall).

Drummer boys and immigrants

“Although the war would drag on another 20 months after Vicksburg, the outcome was pretty much assured,” Winschel said.

The number of casualties to both sides during the siege was 20,000, which was light by Civil War standards, Winschel said.

It didn’t seem so from our vantage point in time.

As we listened to the historian’s retelling of the story, we often stopped to look at the steep ravines that Union soldiers repeatedly charged up in the face of withering fire in unsuccessful attempts to overrun the city’s defenders. Each time, they were beaten back, suffering heavy casualties.

Winschel also breathed life into his account by sharing anecdotes from the battle, including the story of Orion Howe, who at 14 became the youngest person ever to win the Congressional Medal of Honor.

A drummer boy with the Illinois 55th Battalion, Howe volunteered along with three others for a risky mission to race through hostile fire to the back lines to arrange for the resupply of dwindling ammunition stores.

While his three comrades were killed and Howe was wounded, he delivered the message personally to Gen. William T. Sherman, though he apparently garbled the communication, resulting in the wrong type of ammunition being sent to his unit, Winschel said. Nonetheless, the dash made Howe one of just 34 Army musicians to be awarded the medal since its creation in 1861.

We also heard an even more unusual tale of bravery.

In the magnificent Illinois Monument, which is patterned after the Roman Pantheon, Winschel shared the story of Albert Cashire, a volunteer with the 95th Illinois Infantry who fought with distinction at Vicksburg and several other major battles.

After being mustered out of the Army in 1865 at the age of 22, Cashire lived a quiet and unremarkable life for many years, holding a series of odd jobs. But that ended spectacularly in 1911 when his employer, an Illinois state senator, backed over Cashire in his newfangled automobile as he was gardening, breaking his leg in three places.

Cashire was rushed to the hospital, where doctors made a stunning discovery: Albert Cashire was a woman!

It was eventually learned that Cashire was actually Jennifer “Jennie” Hodgers, an Irish immigrant who adopted the male role in order to enlist in the war and then kept up the charade. She was institutionalized, and forced to wear a dress for the first time in decades, but she continued to receive her veteran’s pension until her death.

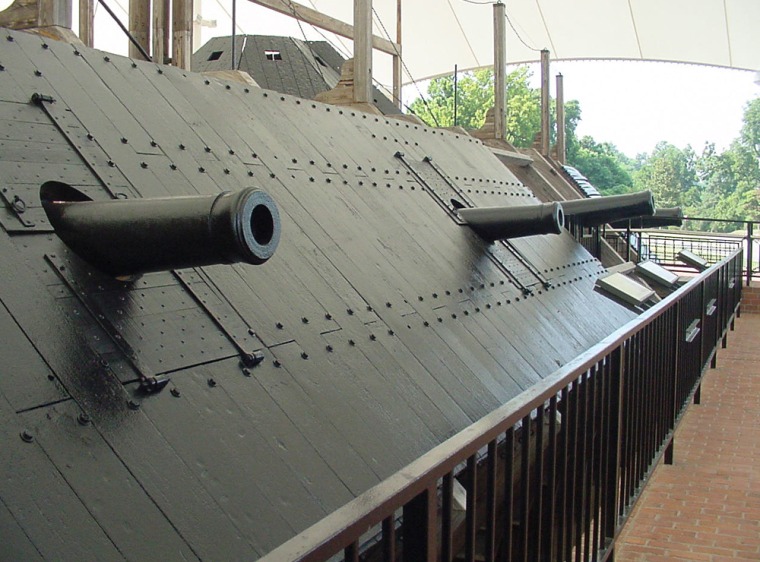

Winschel also guided us through the wreckage of the ironclad USS Cairo, which was the first vessel to be sunk by electronically detonated “torpedoes” – the equivalent of underwater mines today – on Dec. 12, 1862, on the Yazoo River.

The commander of the Cairo, Thomas Selfridge, is thought by some historians to have acted rashly in rushing his vessel to the front of the fleet to confront what he thought was enemy gunfire from the banks.

Winschel said that one Navy wag, upon hearing that Selfridge had been cleared of recklessness in connection with the sinking of the Cairo, wrote in a letter home, “He fulfilled his orders and successfully cleared the channel of torpedoes by placing his vessel on top of them.”

Raised from the river bottom in 1964, the 175-foot armor-plated vessel has been restored and is now on display in a tented outdoor exhibition in the park. Almost as impressive as the ship is the collection of about 1,000 artifacts recovered from the wreck on display at the adjoining museum, including pistols, sabers, a full set of the officer’s china table setting, a working pocket watch, a variety of medicine bottles used by sailors to treat their various complaints and a large supply of ankle and wrist irons.

After completing our tour of the military park, we visited the National Military Cemetery, which is contained within the military park. The cemetery is the final resting place for more than 17,000 the Union’s Civil War dead, more than any other national cemetery, Winschel said.

We spent more than an hour, walking past row upon row of headstones, as well as a stunning number of small square markers denoting the burial sites of unidentified combatants, extend as far as the eye can see across the rolling lawn-covered, beautifully landscaped cemetery.

Since the cemetery is set aside only for U.S. war veterans, Confederate soldiers are interred in Vicksburg’s Cedar Hills Cemetery.

Our visit concluded, we thanked Winschel and resumed our southward journey, heading for a rendezvous with another kind of history in Natchez, Miss., a formerly rollicking river town that recently elected its first African-American mayor since Reconstruction.

Reporter and media producer Jim Seida are traveling the length of the Mississippi in August and will be filing daily dispatches along the way. If you have a question or comment, mail us at mississippi@msnbc.com.