Sniffing out any whiff of biology on Mars has become a scientific battle of the bands — spectral bands, that is.

The purported detection of methane in the Martian atmosphere by Mars Express, the European Space Agency probe now orbiting the Red Planet, has sparked measurable debate.

ESA announced late last March that the Mars Express Planetary Fourier Spectrometer had observed methane. That instrument is built to detect the presence of particular molecules by analyzing their "spectral fingerprints" — the specific way each molecule absorbs the sunlight it receives.

While the amount of methane seen by the spectrometer is very small — about 10 parts in a billion — the implications of the detection are large. Perhaps Mars isn’t a planet waiting to exhale, but one that is a thriving world of panting microbes?

According to ESA experts, methane, unless it is continuously produced by a source, only survives in the Martian atmosphere for a few hundred years because it quickly oxidizes to form water and carbon dioxide — both present in the Martian atmosphere.

So what’s refilling the atmosphere with methane?

Methane measurements

On the one hand, methane production could be linked to volcanic or hydrothermal activity on Mars, although no volcanic activity has been detected on the planet to date.

Alternatively, many types of microbes produce a signature of methane. On Earth, methane is a by-product of biological activity, such as fermentation. Biological sources, such as those associated with peat bogs, rice fields and cud-chewing animals, constantly supply fresh gas to replace that destroyed by oxidation.

"The first thing to understand is how exactly the methane is distributed in the Martian atmosphere," says Vittorio Formisano, principal investigator for the Planetary Fourier Spectrometer at the Istituto Fisica Spazio Interplanetario in Rome.

"Since the methane presence is so small, we need to take more measurements. Only then will we have enough data to make a statistical analysis and understand whether there are regions of the atmosphere where methane is more concentrated," Formisano explained in an ESA press statement.

Ground-based looks

Adding to the Mars Express methane saga are reports from scientists using ground-based telescopes that, indeed, traces of the gas have been spotted.

One independent U.S. team, led by Michael Mumma of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., has also weighed in on the question of methane on Mars.

Mumma reported last year at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences that methane had been detected using super-sensitive infrared spectrometers mounted on the Gemini South telescope on Cerro Pachón in Chile and at the W.M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

The bottom line, Mumma said, is that sorting out the signature of methane is not an easy task.

"I've looked at some of the PFS spectra in the methane region, and am skeptical," Mumma said. "I think they have not yet convinced the community they are detecting CH4 (methane)."

More work is needed to model and strip out the spectra from known constituents within the Martian atmosphere, and then compare the residuals with synthesized CH4 spectra, Mumma said. At this point in time, "the community has reserved judgment on the PFS results," he concluded.

Near the limits of detection

There’s no doubt that detecting methane in the Martian atmosphere would be extremely important if true.

The implication, if it turns out to be really there, is that the methane can only be produced by some active process that churns out new methane — such as volcanic activity or certain types of living organisms known as methanogens. A methanogen is a microorganism that produces methane from the reaction of hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

"In either case, we would have discovered that Mars is an active planet today," said Benton Clark, a Mars Exploration Rover team scientist from Lockheed Martin Space Systems Co. in Denver. "Localizing the source would be of great interest and would point to future exploration."

However, measurements taken to date from Earth and by the Mars Express can be challenged because they are near the limits of detection, Clark told Space.com.

Taking to the air

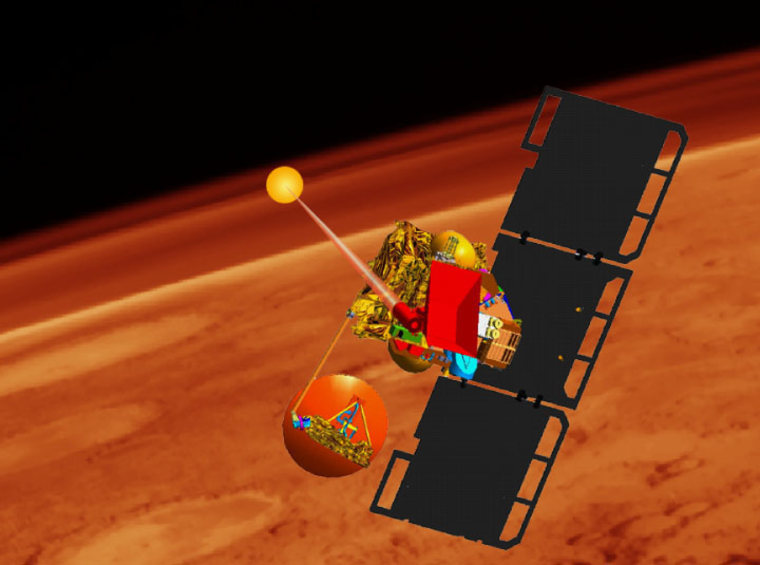

Clark said that the proposed NASA Mars Volcanic Emission and Life Scout mission, known by the acronym MARVEL, would detect methane with 100 to 1,000 times better sensitivity from orbit, and also be able to localize it on the Red Planet.

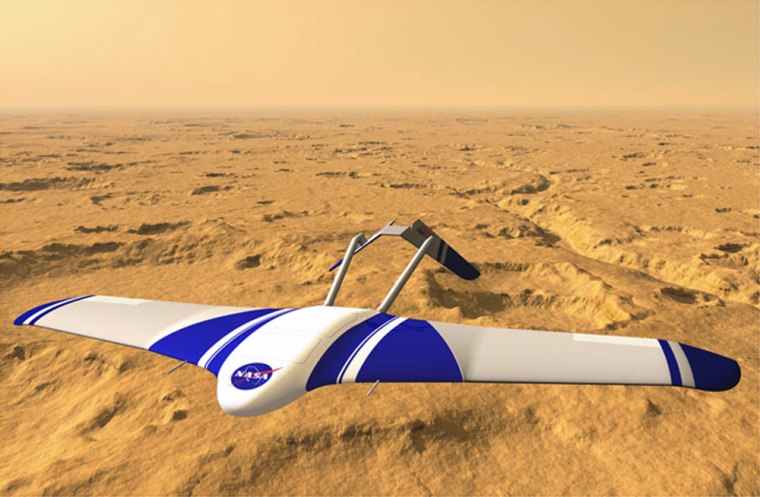

In addition, taking to the air — by flying an airplane over the Martian surface — is another way to spot methane.

For example, Clark said, a proposed Mars airplane, the Aerial Regional-scale Environmental Survey, or ARES), is under the wing of NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va. It is designed to tote instruments that can target methane and other gases for measurement as it flies over Red Planet real estate.

"I think too much has been written about these [Mars Express] observations in the press in the absence of formal scientific review," said Mark Allen, an Earth and planetary atmospheres Research scientist in the Earth and Space Sciences Division at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Allen is the principal investigator for the proposed MARVEL Scout.

Without peer-reviewed assessments of the Mars Express findings, Allen said, any comment on the observations would be premature.

"At best these observations are tantalizing, since the experiment seems to be operating at the limit of its sensitivity. However, the implications for extant habitability and inhabitance of Mars are tremendous," Allen said. "I would hope that NASA is interested in pursuing this subject and might find a mission with much more sensitivity and capability for locating surface point sources — such as MARVEL — highly attractive for selection next time," he suggested.

Proceed with caution

Also in the still-to-be-convinced category in regards to the Mars Express methane finding is James Garvin, NASA chief scientist for Mars and the moon, in the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

"Most of what we have seen from the Mars Express PFS does not yet suggest that it is wholly reproducible and even localizable," Garvin suggested. His advice, as a NASA scientist steeped in ever-growing volumes of new Mars data: Proceed with caution, examine multiple lines of detection and then the basic chemistry of the processes — before leaping to conclusions.

Garvin noted that the instrument on Mars Express is an outstanding Fourier spectrometer which could, under appropriate circumstances, detect methane at levels of tens of parts per billion — but across a large control volume of the Martian atmosphere which is relatively well-mixed.

There is far more evidence, Garvin continued, for the possibility of recent, highly localized volcanism — such as fumaroles or local hydrothermal vents — than for anything to do with subsurface microbial systems.

"If you were to ask me, any methane we may be seeing must be volcanogenic on the basis of what scant real scientific evidence we have ... or it could even be some sort of ‘oddball’ result of asteroidal impact that we have not fully understood," Garvin speculated.

Looking to the future, Garvin pointed to the launchings of NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2005, the Phoenix lander in 2007, and the wheeled Mars Science Laboratory in 2009.

Each will help puzzle out further the Red Planet’s past history and present-day condition. And each will, at least in part, address the existence of disequilibrium trace gases — such as methane — using new approaches, including on-the-spot mass spectrometry, he said.