Just after you let a car cut in front of you, it brakes and forces you to wait until it makes a left turn. Chances are, your hand quickly finds its way to the horn.

We often feel the urge to teach cheaters and other rule-breakers a lesson, even when we don’t seem to benefit from doing so. A Swiss study now suggests a possible motivation: penalizing rule-breakers activates a part of the brain involved in experiencing pleasure.

Although our “tit for tat” behavior may seem childish in some cases, it also appears to be a basic human quality that allowed our ancestors to form cooperative societies, according to Ernst Fehr of the University of Zürich and his colleagues. Their study appears in Friday's issue of the journal Science, published by AAAS, the nonprofit science society.

Is fairness in our self-interest?

Economists have long assumed that human behavior is essentially rational, meaning we don’t do something unless we somehow benefit from it. In fact, self-interest seems to motivate most behavior in the animal kingdom.

Of course, animals can behave in ways that appear purely altruistic, such as parents caring for their young. Some researchers have argued, though, that these acts are self-interested from an evolutionary point of view, since they improve the chances that the family’s genes get passed down.

Although the “me — or my genes — first” model does explain a lot about how we behave, it doesn’t at first glance explain the social norms involved in human cooperation.

We wait in line with people who aren’t our relatives and allow them to save seats in movie theaters; sometimes we even give them interest-free loans. And we feel betrayed if we don’t receive the same treatment in return.

“We know that this desire for retaliatory justice is very widespread,” Fehr said.

An ancient inclination

Teaching social rule-breakers the error of their ways may be as simple as a blast of the car horn in response to an inconsiderate driver.

At the other end of the spectrum, if your uncle Claudius kills your father and marries your mother, you may start moping over skulls and plotting his demise. Revenge has long been fodder for popular dramas, from Sophocles to Shakespeare to "Seinfeld."

In fact, the desire to retaliate against those who have wronged us or otherwise broken social rules probably goes back all the way to the earliest human societies. Before the days of modern law enforcement, people living together still had to follow common rules, or norms, for their behavior.

Or course, just because the instinct to get even may be partly rooted in our biology, “that doesn’t imply in any sense that we should allow private revenge. It only means that we can explain why people do this,” Fehr said.

Getting some satisfaction

Fehr and his colleagues set out to determine whether the human brain might provide motivation for what they call “altruistic punishment.”

They organized pairs of male volunteers to play a game in which both players began with the same amounts of play money. Player A could choose to give player B his money, and if player B returned the favor, both players would be rewarded with an extra sum.

If player B kept all the funds, however, player A could impose a penalty that cost player B a portion of his money.

The researchers monitored the brain activity of player A as he made a decision about penalizing player B. (Player A almost always decided to do so, even if he had to give up his own money in the process.)

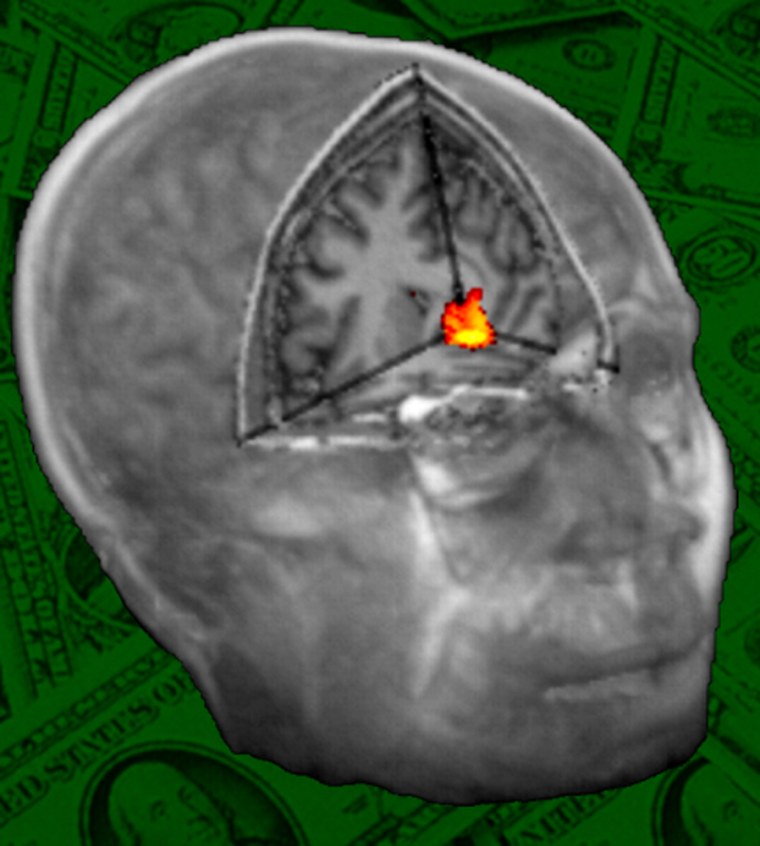

Fehr’s team found that imposing the penalty activated a brain region called the dorsal striatum, which is involved in experiencing pleasure or satisfaction.

“We found large differences across subjects in reward-related brain activity and the associated willingness to spend money for punishing an unfair player,” said co-author Dominique de Quervain of the University of Zürich.

“These findings reflect the everyday experience that some people are willing to invest much more than others in punishing norm violations,” he added.

‘Go ahead, make my day’

At this point the researchers had discovered a correlation — that the pleasure-related brain activity occurred along with inflicting the punishment — but a deeper question remained: Did one experience cause the other?

Further experiments indicated that inflicting the punishment didn’t cause the players to feel satisfaction. Instead, as they decided to impose the penalty, the players were anticipating feeling satisfied.

And that, Fehr said, is as rational a motivation as any.

“You can look at our experiment as saying that people seem to feel rewarded when they punish a defector,” he said. “Now there is nothing irrational about feeling rewarded about eating a chocolate. Similarly, there is nothing telling us that altruistic punishment is irrational.”

“As with any compelling study, the findings raise additional questions for future research,” Brian Knutson of Stanford University writes in a “Perspective” article that accompanies the Science study.

For one thing, people approach both cooperation and fairness quite differently from one society to the next. Anthropologists have observed very little altruistic punishment in some small-scale societies and much more in others.

"Altruistic punishment is likely to be shaped by cultural forces, because we know from cross-cultural studies that the propensity to punish social norm violations varies widely across different small-scale societies" said Fehr.

Also, the researchers only studied men. The team also interested in investigating whether women’s brains work the same way.