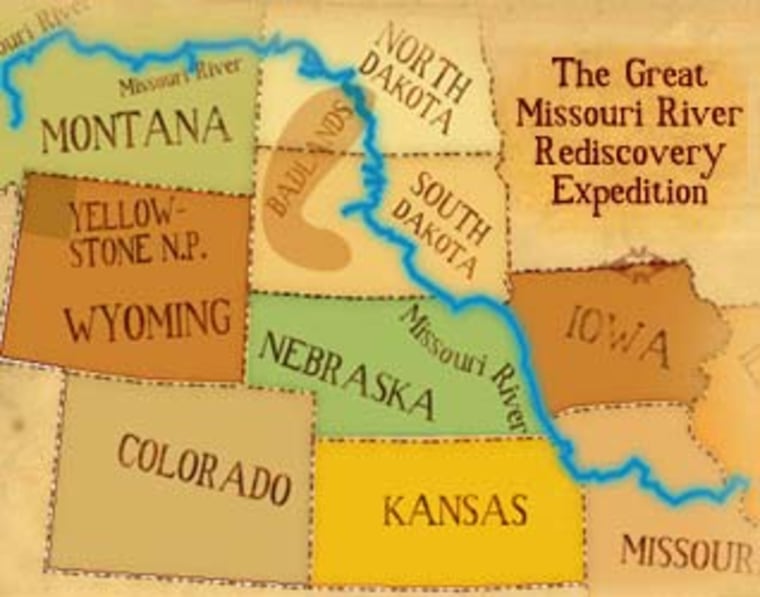

It’s the longest river in the United States, 2,540 miles – longer than the Mississippi by almost 200 miles. Its watershed covers about one-sixth of the 48 states, draining all or part of nine states, more than half a million square miles. When Lewis and Clark set out from St. Louis to explore a land unknown, they traveled by way of the Missouri River.

Now we’ll be going the other way, from the source in the Centennial Mountains of southern Montana downstream, retracing the epic route in reverse. We’ll see that some things have changed dramatically, thanks to increased human population and the impact of civilization. And we’ll see that some things have remained the same.

Our team to explore this river of adventure isn’t quite in the class of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, but they're all experienced, capable and creative media explorers. Correspondent Richard Bangs is author of over dozen travel books and the executive producer for Great Escapes. His colleague in adventure P.V. Scaturro joins him on this trip, as he did on the Great Escapes: Colorado in 2003, as co-producer. Photographer Didrik Johnck again focuses his digital eye on the action, as on Great Escapes: Texas where he shot and edited the videos. Finally, Andrew Locke of MSNBC’s Interactive Media team comes aboard as video and audio producer.

While we’ll use some of the traditional conveyances of the original journeys – canoes, horseback, boots – we’ll cover most of our miles by stitching together a highway route along the great river, following main roads, dirt tracks and byways. Our vehicle of choice is distinctly modern: the new Ford Hybrid Escape, the most in-demand four-wheel drive car available today. It runs on a high-tech improvement on the standard internal combustion engine, with better mileage, cleaner emissions, and quieter performance.

From source to sea

One of the mysteries of the Missouri remains its source. Map makers like to mark it at the confluence of the Gallatin, Jefferson and Madison rivers at Three Forks, Montana. But some think that the feeder with the highest volume should be traced to its beginnings and claimed as the true font. Others contend that the first occurrence of moving water in a river shed farthest from the mouth wins the prize.

So our journey begins on the banks of the Yellowstone River, one candidate for the source. Although it’s designated a “tributary” of the Missouri, when the Yellowstone joins the Missouri at Buford, North Dakota, it is the larger of the two streams, and as such may claim bragging rights as the real source. There are other reasons for visiting the Yellowstone: it’s the longest remaining undammed river in the contiguous United States, and it gives its name to the charter member of the National Parks system.

Then we’ll head west to little-known Centennial Valley, and ride up an obscure brook called Hell Roaring Creek to where water first bubbles from the ground. This creek has only recently been recognized the tributary farthest from the river’s egress, over 2500 miles away, when it joins with the Mississippi.

To complete our mission, we explore Three Forks, where the combined stream is first called the Missouri. Then we follow the river as it swings north, passing through the Gates of the Mountains, a narrow canyon with sheer walls over 1,000 high. At Great Falls, Mont., the river cascades over five waterfalls, dropping more than 500 feet in 12 miles. Meriwether Lewis called it "a superbly grand spectacle,” and we’ll see if times have changed in this mid-Montana town.

Turning east, the river slices through the Missouri Breaks and a designated Wild and Scenic stretch near Ft. Benton, with archaeological sites, bird nesting areas, sandstone bluffs and the White Cliffs where Lewis and Clark camped. It slows and fattens as it feeds Fort Peck Lake, one of the largest man-made reservoirs in the world, amid the classic landscape that inspired Charles M. Russell and many other “cowboy artists,” breathing with history and the wide-open spaces of the West.

Beyond Fort Peck the Missouri flows into North Dakota, where it is at last joined by its larger tributary the Yellowstone. Now we’re in the Badlands: sculptured into fantastic shapes by the erosive power of the Little Missouri, small buttes and peaks surrounded by deep gullies and ravines. This is the area a young Teddy Roosevelt hunted and later ranched, leading him to comment, "I never would have been President if it had not been for my experiences in North Dakota." It is sure to be an off-road test for our hybrid Escape.

Old Man River

Then the old man rolls south to Bismarck, North Dakota’s capital, though many areas set aside as tribal lands for the region’s first inhabitants, and through open range where the buffalo still roam. Past Pierre, the river turns southeast and forms the boundary between South Dakota and Nebraska, running through America’s heartland. At Yankton, the water works its way through Gavin’s Point Dam, the last on the Missouri, and meanders down to Sioux City, Iowa.

The Missouri is joined by the Platte River just beyond Omaha, and forms state boundaries between Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri and Kansas, until it reaches the largest and bluesiest city along the Mighty Mo’, Kansas City. Count Basie, Lester Young, Charlie Parker and other innovators in jazz and swing started their careers here, syncopating to the rhythms of the river. Then the Missouri turns sharply eastward, across the heart of the state that proudly wears its name until it finally blends its currents and its history with the Mississippi at Missouri Point, a few miles north of St. Louis.

Looking back on his exploration of the Missouri River a bicentennial era ago, Col. Meriwether Lewis wrote, "It seemed as if those scenes of visionary enchantment would never have an end." For those who join us on our great escape down the Missouri river, we can make that enchantment last a little while longer.