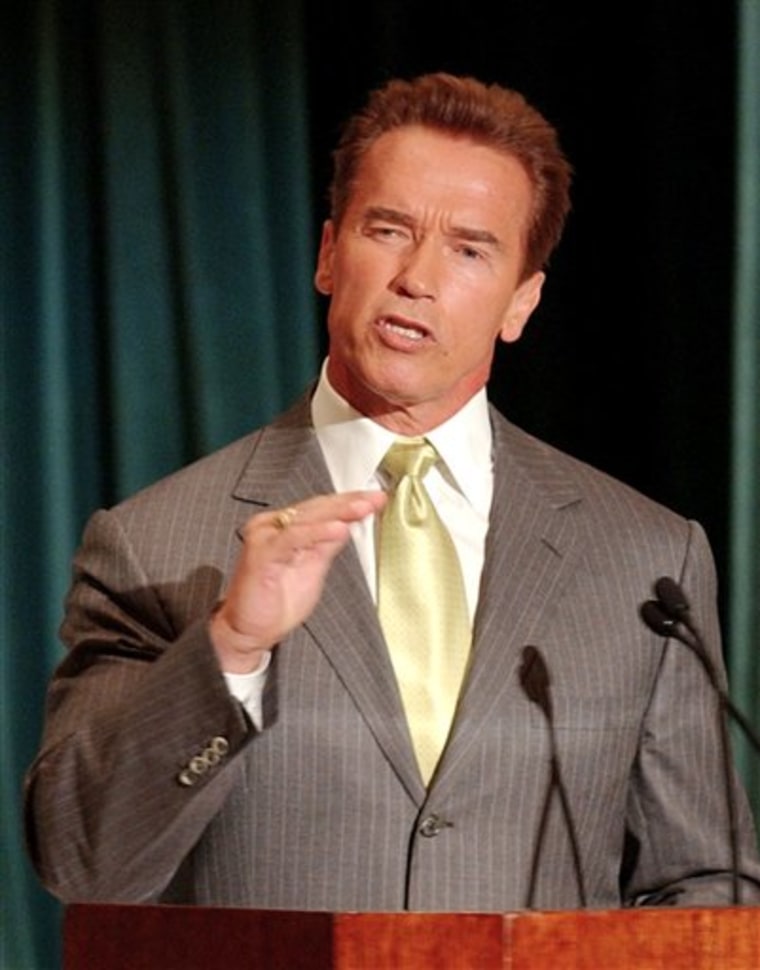

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger's ambitious plan to reorganize almost every aspect of state government was influenced significantly by oil and gas giant ChevronTexaco Corp., which managed to shape such key recommendations as the removal of restrictions on oil refineries.

Many corporations and interest groups participated in the governor's reform plan — known as the California Performance Review — but state records and interviews with the participants show Chevron enjoyed immense success in influencing the report through its array of lobbyists, attorneys and trade organizations.

And few corporations have spent so much political cash on the governor, either. Since Schwarzenegger's election last October, the San Ramon company has contributed more than $200,000 to his committees and $500,000 to the California Republican Party.

Chevron, whose officials acknowledge they lobbied hard to get their ideas in the report, is one of about 20 companies that paid to send the governor and his staff to this week's Republican National Convention in New York. On Wednesday, Schwarzenegger attended a closed-door meeting in New York with representatives of those companies, including Chevron. And just three weeks after the governor's office released the 2,700-page reorganization report, the company gave $100,000 to a Schwarzenegger-controlled political fund.

Environmental watchdogs and local agencies that regulate some of Chevron's operations complain that they had no such access, and that their counterproposals appear nowhere in the massive report.

Billy Hamilton, co-executive director of the Performance Review, said the report's authors were not influenced by Chevron and that special interests had no role in the production of the report.

"I don't believe that's what took place," said Hamilton, the deputy state comptroller of Texas. "I went through these issues myself. I know these people who did the reports; none of them had anything to gain."

Disclosure of Chevron's determined role in what many believe is the administration's most important political reform effort contrasts sharply with statements he made during last year's election campaign and afterward in which he promised to sweep out a corrupt system where "contributions go in, the favors go out."

Schwarzenegger launched the reorganization effort in January, calling the state bureaucracy a "mastodon frozen in time" that needed to be reviewed from top to bottom to eliminate waste and duplication. The administration said the recommendations in the report would save $32 billion over five years, a claim analysts said is exaggerated.

Although the governor's senior aides helped organize and oversee the reorganization effort, a spokeswoman for Schwarzenegger said the review staff, not the governor's office, was responsible for the report. Schwarzenegger announced the review in January and then appointed its two top members, who then assembled the rest of the staff.

Ashley Snee, the governor's deputy press secretary, said it was premature to assume any of the recommendations will be adopted and that those who are unhappy with parts of the report can comment at a series of statewide hearings on the proposal.

Proposals that would benefit Chevron are peppered throughout the four-volume report. They include:

- Streamlining the permit process for the construction of new oil refineries and the expansion of existing ones. Chevron, which owns two of the state's largest refineries in Richmond and El Segundo, wanted the state's help in revising existing laws so local government officials would be required to make decisions more quickly on construction permits at refineries.

- Streamlining the activities of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission. That agency, which issues permits for dredging and sand mining in the Bay Area, oversees activities related to Chevron's interests in the Bay Area.

- Reorganizing the regulatory process for picking the locations for refineries, tank farms, liquefied natural gas and other energy facilities. Chevron has two proposals to build liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities in Southern California and the Mexican state of Baja California.

"California's ability to produce gasoline is shrinking at the same time demand for gasoline is rising, contributing to California's dubious position as a national leader in the fuel prices. Time-consuming, costly and complex permitting processes are among the obstacles to expanding ... California's petroleum infrastructure to meet the growing demand," the CPR report said. "The state needs to streamline its permitting processes to allow supply to more readily keep pace with demand, so that price volatility and price differentials are reduced."

But Mark Petracca, a University of California, Irvine political scientist, said Chevron's considerable influence on the CPR report may taint the whole review because the study was presented to the public as an objective and authoritative analysis of how to fix state government.

"This is good old fashioned interest-group politics," Petracca said. "Powerful people who have money can hire powerful people and use occasions like this report to set the agenda for policy beneficial to those interests."

In response, Snee repeated that the report was independent of the governor's office.

Chevron's operations have drawn steady and critical scrutiny from state and federal regulators, including a settlement last October of a lawsuit with the U.S. Justice Department that required the company to install $275 million in air pollution equipment and pay $3.5 million in civil penalties.

Company officials said they were just doing their jobs through their vigorous participation in the CPR process, which included meeting with senior aides to the governor.

"This is what we are here for," said Jack Coffey, Chevron's general manager over state government relations, from New York where he was attending the Republican convention.

Chevron learned about the CPR early and "obviously understood their agenda," Coffey said, adding that while there was direct contact by company lobbyists, most contact came through trade groups of which Chevron is a member. "We made an effort to feed those trade associations who were more active."

But, Coffey said, Chevron's donations to Schwarzenegger are because of his "pro-business agenda" and have nothing to do with the CPR report.

In an interview, Chevron lobbyist K.C. Bishop said he met with Richard Costigan, Schwarzenegger's legislative affairs secretary, in April or May, about trouble the company was having with routine refinery permits and proposed legislation on the issue. At the end of the discussion, Bishop was directed to the CPR staff, which he visited a week or so later.

Neither the meeting with Costigan nor with CPR staff were reported in Chevron's quarterly lobbying filings.

Also acknowledged in the CPR report were Bishop; Mike Barr, a lawyer with the San Francisco-based firm Pillsbury Winthrop and who represents Chevron; and affiliated lobbyists of the Western States Petroleum — Kahl/Pownall Advocates — of which Chevron is also a member.

Meanwhile, the Bay Planning Coalition — a business-oriented group of which Chevron is a board member — contacted the governor's cabinet secretary over problems its members were having with the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission.

Schwarzenegger's staff sent the coalition's issue to the CPR staff, which met with the coalition sometime in April, according to Ellen Johnck, the coalition's executive director.

A letter from the coalition outlining the complaints — including some lodged by Chevron — was used as a primary source for the CPR report, which concluded that BCDC had overstepped its authority. Although BCDC officials offered significant documentation to rebut the allegations, none of the commission's defense was included in the CPR report.

In its section about making it easier to locate refineries or LNG plants, the CPR report cites attorney Mike Carroll of the law firm Latham & Watkins as a source. Based in the firm's Orange County office, Carroll represents Chevron on a variety of regulatory issues, according to the firm's Web site.

Carroll did not return telephone calls for comment from The Associated Press.

Chevron has two LNG proposals — a $650 million facility that would be built offshore on an island near Tijuana in Baja California; and a second plan that would place a facility at Camp Pendleton in Orange County.

Schwarzenegger is expected to meet with Mexican officials in Mexicali later this month. One expected topic of discussion is Chevron's LNG proposal.