With the crinkly smile of someone cursed with an utterly satisfying career, Yellowstone back-country ranger Chester Kellen, 78, volunteers he has been “well-paid….in a non-material sense,” by his summer employer of 45 years, the National Park Service.

In the winters, until retiring last year, he was a philosophy professor who pondered the meaning of wilderness. He thought, and taught, about how we make decisions, such as whether and how to control wildfires, the re-introduction of wolves, the introduction of non-native fish, the sanctioning of snowmobiles, or determining the environment’s carrying capacity of internal combustion cars. “Until we understand the relationships between all ecosystems, locally and globally, inside our own human bodies, and externally, we aren’t really dealing with wilderness. Or anything else.”

Then we show Chester our means of conveyance to explore the park, a fresh-from-the factory Escape Hybrid SUV. He beams. “More than a million cars drive through Yellowstone each year,” he states, standing in front of a monitor gauging air quality. “Triple the number of when I started.

“This car,” and he stoops to slide inside the Escape, which is idling with the roar of a golf cart, “is the future.”

The Clark and Lewis Trail

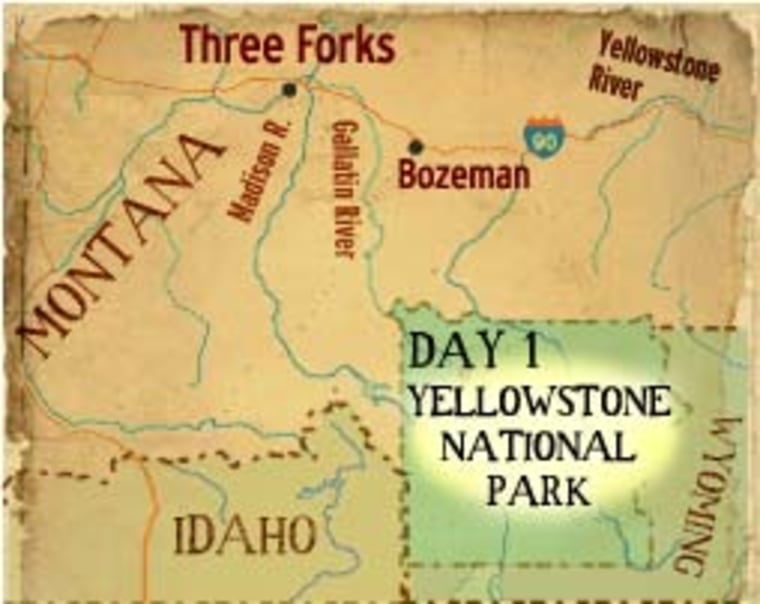

We’re four on the road, looking for adventure, and the future. Our goal: to drive the length of the Missouri River, following for large portions the trail that Lewis and Clark pioneered 200 years ago, but in the opposite direction. (The Clark & Lewis Trail, perhaps?) But in a way we’re pioneering as well, driving the first gas-and-electric hybrid four-wheel-drive SUV, the most environmentally-friendly backcountry car available, down alongside America’s longest river.

We begin our trek in Yellowstone, America’s first and favorite national park, because it’s the source of three of the primary feeder streams to the Missouri – the Gallatin, Madison and Yellowstone rivers. It’s a busman’s holiday for this corps of re-discovery. Pasquale Scaturro recently returned from making the first full descent of the Blue Nile, from source to sea, and is intrigued with following America’s counterpart, the Missouri. Didrik Johnck just got back from Tibet. Andrew Locke was covering stories in Macedonia and Vietnam. And I’m not long back from a trek in desert-dry Libya, ready again for moving water. What better adventure for us than the Mighty Mo?

Joining us for the day is Jeremy Roberts, 30, the staff naturalist at Papoose Creek Lodge, an upscale eco-lodge outside the park. Jeremy has been fascinated with the way Native Americans lived in the Yellowstone region in the time of Lewis and Clark, and he carries with him a duffel bag of accoutrements he has fashioned from the era: a knife made of obsidian, moccasins crafted from moose hide, arrows with turkey feathers, a rock hammer held together with elk sinew and sap.

He is a man who celebrates the more ecologically balanced life past, and as we enter Yellowstone from the west entrance he winces as we pass a line of cars parked on the side of the narrow road. A score of amateur paparazzi are stepping into an adjacent field, pointing cameras at a bald eagle’s nest about 100 yards off the road. Nearby is a large sign that says “Don’t Stop.” It’s a special management area, as the park doesn’t want the mother eagle stressed with encroaching tourists. But these photographers just ignore the request, and proceed in their private quest to shoot the great bird.

As it turns out Jeremy is himself a photographer of sorts. He’s been taking photos for the past year of inappropriate behavior in the park, something he hopes to turn into a book. He has shots of folks dipping “chubby Cheeto-flavored fingers” into hot springs in front of signs forbidding such. And shots of tourists stalking one-ton, woolly-headed, big horned bison, who can run three times as fast as a human, and have been known to gore losers in the race. Then on cue we round a corner and see a busload of tourists stepping through the grass towards a herd of elk. Jeremy jumps out of the Escape and stalks the tourists, capturing more images for his book.

At the local bookstore the salesman says the most popular tome is “Death in Yellowstone: Accidents and Foolhardiness in the First National Park,” with its graphic descriptions of those who fell over 300’ waterfalls, into 200 degree Fahrenheit pools, or ended up on the business end of a horn or antler.

Charter member of the National Park System

Yellowstone is the world's first national park, created in 1872. It was its tourist potential that saved it from development. Railroad executives looking to expand their passenger base pressured Congress to set aside the land, arguing it was useless in any other commercial way. High in the mountains, it was inaccessible, unfarmable and no gold had been found in it. They pointed out America did not have the kinds of cathedrals, castles and cities that Europe did, but it did have natural wonders, among them the geysers and “glass mountains” of Yellowstone. Congress set the land aside, and the railroad arrived 11 years later.

More than 125 million people have visited Yellowstone since, a rectangle of land filling a corner of Wyoming and spilling into Montana and Idaho. The area is 63 miles north to south and 54 miles east to west, bigger than Rhode Island and Delaware combined. And 90 percent of the 3 million people who enter the park each year never leave pavement or boardwalks.

We make the usual pilgrimages, to Lower Yellowstone Falls dropping into the golden Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River; to Mammoth Hot Springs; Yellowstone Fort; Angel Terrace, Liberty Cape, Palette Springs. It is the prevalent rhyolite, an eroded lava rock that gives Yellowstone its name. “Paint cannot touch it and words are wasted,” said painter Frederic Remington in 1895.

Yellowstone is cinematic, ever moving, always reeling. We hew by steaming vents, burping mud pots, bubbling fountains and hissing fumaroles. It is one of the most geothermically active spots on Earth, “a geological freak show,” as Jeremy says – a continuing legacy of its violent volcanic origins.

And along the way we find ourselves stuck in “bear jams” every mile or so as cars halt and pull over pell-mell whenever wildlife is to be seen off the road. A couple times we inch past lines of idling cars and tourists with cameras and binoculars pointed to some middle distance and we stretch necks and sweep the landscape for the attraction, but can see nothing. The only herds are the tourists.

At last, after a full day exploring the park, I need to heed nature’s call. So, we pull over at a rare roadside quiet spot dense with vegetation, and I disappear to go see a man about a horse. When I return a line of cars have parked in front and back of the Escape, and crowds of people are out of their idling cars hunting for the shot of the animal I must have seen. I hop back in the car, and quietly we motor away down the open road.

The Great Escapes media team is traveling the length of the Missouri River in September, filing daily dispatches along the way. If you have a question or comment, mail us at greatescapes@msnbc.com.