The trouble began, Sue thinks, when her mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease 10 years ago. Her dad, now 88, slowly became obsessed with having enough money to pay for his wife's health care. To Clyde, answering a few of those promising sweepstakes entries that come in the mail seemed innocent enough. Send in $10, they say, to claim your $10,000 prize -- or some slight variation.

"He's obsessed with caring for my mother," said Sue, a Harrisburg, Penn.-area, resident who asked that her father's anonymity be protected.

At first it was a trickle, then a flood. Now it's a tidal wave. Three shopping carts full of mail sit in the basement. And Clyde can't help himself -- he continues to fill out the entries and send in his money, chasing after a dream. He's spent some $15,000 in $10 and $20 increments over the last two years, Sue estimates. There's so much junk mail that the local post office, aware of Clyde's problem, has begun quietly siphoning it off, to keep it from the house.

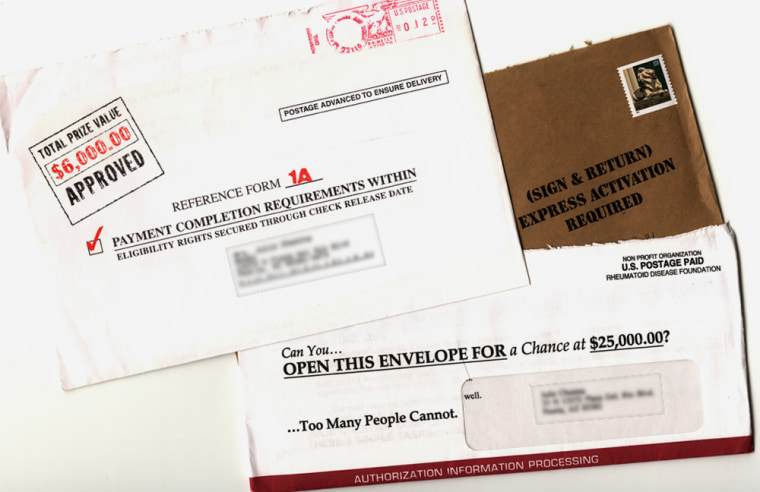

Why is Clyde, and so many other Americans around the country, being deluged with contest entries? Because, authorities say, the sweepstakes are just the tip of the iceberg, a window into a highly organized world of con artists bilking U.S. citizens -- often the elderly -- out of millions of dollars.

Criminals go fishing

Many cleverly-designed sweepstakes entries are really just a fishing expedition by con artists. Fill one out, send in the money and criminals know you are gullible. Your name and contact information land on what's known in the business as a "sucker's list," and it's sold over and over again to con artists.

What follows is a deluge of fraudulent telemarketing calls, almost always from Canadian-based con artists. If you'll pay $10 for a dream, the thinking goes, you'll probably pay $100, $1,000, or $10,000. Sometimes even more -- much more. Federal investigators say fraudulent sweepstakes entries have reached near epidemic proportions, particularly among the elderly.

It's hard to estimate the size of the problem, but individual incidents provide a glimpse. At one commercial mail drop in Clive, Iowa, the Iowa state attorney general's office last December recovered 22,000 entries that had been filled out in response to a single sweepstakes mailing. Each one included a $10 or a $20 payment.

"It's a huge problem," said Steve Sinclair, an investigator with the Iowa attorney general's office.

Many of the completed entries end up in Iowa, Sinclair said, where they are picked up and forward to other locations, often to Canada. Iowa seems like a harmless place, which is why con artists invite contest entrants to send mail there, he said.

The attorney general's office in Iowa has been raiding mail boxes for years, seizing thousands of completed sweepstakes forms, issuing press release and warnings. Still, the contest entries come, with no end in site. And they are quite an ingenious tool for finding potential victims, Sinclair said.

"The consumer is actually spending a very small amount, but they are demonstrating a willingness to send money off to a stranger in a far away place," he said. "As a result, [con artists can] cast the net pretty broadly and end up with a pretty hot list of leads."

An easy target

When the phone calls come, telemarketers lure their marks with stories of hot stock tips or explanations that they are already entitled to lottery prizes -- a small fee to cover a tax payment is all that stands between the consumer and $100,000 or more, the caller says.

The elderly can be easy targets. Many grew up in a different time, when everyone deserved immediate respect, said Eric Friedman, an investigator with the Montgomery County Division of Consumer Affairs in Maryland.

"They are not accustomed to slamming the phone down, not accustomed to being impolite," he said.

In Clyde's case, the contests have become an addiction, a local therapist said. Sue took away her father's checkbook, but he still gets money orders and continues to fill out the entry forms and send them off.

Her father just cannot give up his dreams, Sue said.

"He doesn't believe it's a scam," she said. "You read the letters and it sounds like you are winning, it's so deceiving. We talked to him. The counselor talked to him. His lawyer talked to him. His accountant talked to him. But he still thinks it's real."

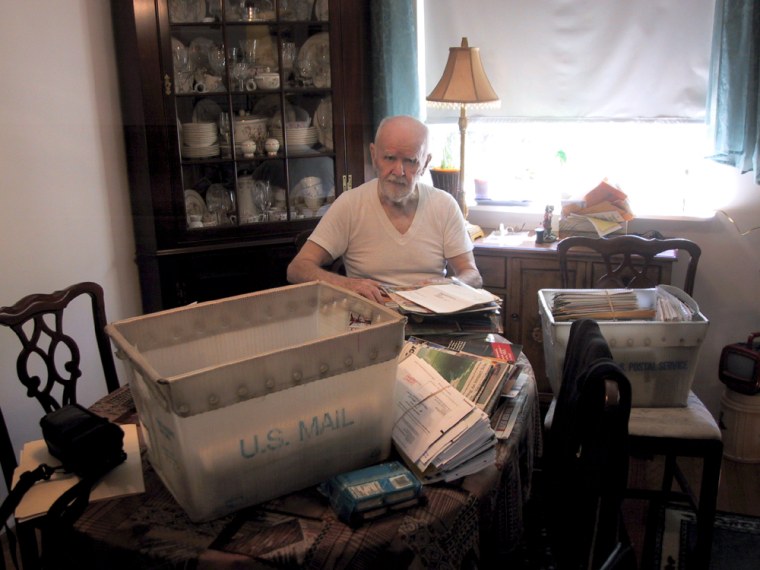

John Fox, an 81-year-old Montgomery County, Maryland resident, is now getting so many sweepstakes entries it's hard for him to find his Social Security check in the pile of mail.

"They made all kinds of promises," Fox said. "But I never got anything out of it."

Fox lost thousands of dollars a month to the scam artists before the consumer affairs office intervened, Friedman said. During one visit to Fox's home, the telephone was ringing off the hook, the investigator said.

"This is somebody who worked all his life, and he had a minor stroke and he's doing the best he can to deal with it," Friedman said. "We're trying to reeducate him. Maybe we convinced him these guys are all crooks. But deep down he thinks one of these days he's going to win."

Luring potential victims slowly, a few dollars at a time, is an old trick, said Molly McMinn, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Postal Inspection Service.

"If someone will send you $1, maybe they'll send you $5," she said.

A billion-dollar industry

The arrival of deep-discounted international telephone services has exacerbated the problem. Canada - particularly Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver -- has become a haven for telemarketing boiler rooms. Phonebusters, a cooperative effort between U.S. and Canadian law enforcement agencies, estimates phone fraud to be a $1 billion a year business now. The FBI estimates that U.S. citizens send $100 million each year to Canadian con artists. And in the fiercely competitive world of telemarketing fraud, con artists are constantly searching for new hot leads.

Friedman and Sinclair both urge adult children to pay attention to their parent's junk mail. If a trickle of sweepstakes entries suddenly becomes a flood, sit them down and ask about it. Asking for a glance at their checking accounts is a good idea too: Many senior citizens are private about their finances, and when they've fallen for a scam, are often too embarrassed to admit it.

There is one piece of good news: even if the deluge of mail has already started, it can be blunted. Friedman said that con artists do pay attention to who answers the mail, and who ignores it.

"The more you don't respond, the less you will be on a list," Friedman said.

"Dateline NBC" producer Sandra Thomas contributed to this report.