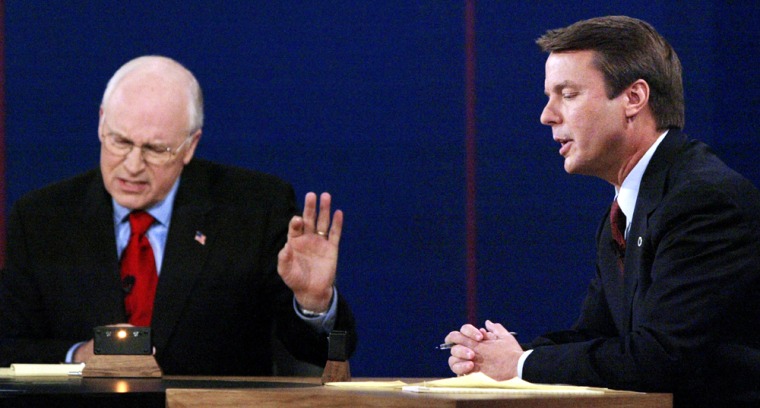

Vice President Dick Cheney and his Democratic opponent, Sen. John Edwards of North Carolina, clashed sharply Tuesday night over the Bush administration’s handling of the war in Iraq in a remarkably contentious vice presidential debate, the only time they will face each other head to head.

Cheney was immediately asked about statements by the former U.S. administrator in Iraq, L. Paul Bremer, that the United States had “” for insufficient troop levels after the war. But he chose not to respond to Bremer’s comments directly, saying only that the U.S. policy was correct and using his answer to return to the Bush campaign’s favored theme that Iraq was better off without Saddam Hussein in power.

Edwards pounced, opening his rebuttal by accusing Cheney of “not being straight with the American people.” He recounted the history of rising U.S. casualties in Iraq after President Bush declared the end of “major hostilities” last year and said Bush’s policies were misguided. Edwards said that the military had been “heroic” but that the United States needed a “fresh start” to put more troops on the ground, speed up reconstruction and create a new international coalition.

When Cheney reminded Americans of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and again raised the specter of Saddam’s remaining in power had the United States not acted, Edwards declared, “There is no connection between the attacks of September 11 and Saddam Hussein.”

Cheney turned on the Democratic presidential nominee, Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts, saying he had seen “no evidence” that Kerry was willing or able to confront terrorism.

Although the accusations were delivered in a low-key manner, the exchange over Iraq was notably contentious. Within the first 10 minutes of the 90-minute debate at Case Western Reserve University, both men accused the other and their bosses of intentionally misleading the public and not having the backbone to stand up to terrorists.

“You’re not credible on Iraq because of the enormous inconsistencies John Kerry and you have cited time after time after time in the campaign,” Cheney said. “There’s no indication at all that John Kerry intends to carry through on the war on terror.”

“What Dick Cheney just said was a complete distortion,” Edwards replied.

Cheney said Kerry began talking tough on Iraq only after former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean began making gains in the Democratic primaries by running on an anti-war platform.

“If they couldn’t stand up to the pressures that Howard Dean represented, how can we expect them to stand up to al-Qaida?” Cheney asked.

Edwards again and again characterized Cheney’s defenses of the war and the U.S. diplomacy that led up to it as “distorted,” “misleading” and “wrong.”

At one point when asked to respond, an exasperated Cheney complained: “It’s hard to know where to start. There are so many inaccuracies there.”

Warmup for Bush-Kerry II

Polls show a tightening race and suggest that Kerry gained ground last week in the first presidential debate, which was devoted to foreign policy. It, too, was dominated by the war and had been expected to give Bush the best opportunity for his strongest performance.

Republicans were looking to Cheney, the strongest advocate of the war in the Bush administration, to return public attention to the Sept. 11 attacks and to make an effective case for the war.

Edwards had been expected to make a major issue of Cheney’s position before joining the Republican ticket in 2000 as chief executive of Halliburton Corp., the military contractor that Democrats charge has benefited from the war thanks to its ties to the administration. Halliburton won some Defense Department contracts for Iraq without competing, and government auditors found that it overcharged for fuel and food.

But it was the moderator, Gwen Ifill of PBS, who first mentioned Halliburton, reminding Cheney that when he led the company, he said U.S. firms should be allowed to do business with Iran despite U.N. and U.S. sanctions.

Asked whether he still felt that way, Cheney said no. He said continuing pressure on Tehran had persuaded other countries in the region to yield to U.S. demands on weapons of mass destruction, specifically mentioning Libya’s agreement to dismantle its nuclear weapons program.

Edwards used the opportunity to attack Cheney on Halliburton, likening it to Enron Corp. and accusing the administration of giving it billions of dollars in new contracts. His attack was misleading, however, neglecting to account for congressional auditors’ conclusion that U.S. officials met legal guidelines in awarding the business without competition, in part because Halliburton was the only company capable of doing some of the work.

Cheney called Edwards’ charges a “smokescreen” and, even though the segment of the debate devoted to foreign policy was still under way, switched tactics to attack Edwards’ Senate record, telling him: “Senator, frankly, you have a record in the Senate that’s not very distinguished.”

Continuing to address Edwards directly in violation of the ground rules, Cheney said: “You’ve got one of the worst attendance records in the United States Senate. Now, in my capacity as vice president, I am the president of the Senate, the presiding officer. I’m up in the Senate most Tuesdays when they’re in session. The first time I ever met you was when you walked on the stage tonight.”

Edwards did not respond specifically, saying only that “that’s a complete distortion of my record.”

Democrats noted afterward that Cheney was incorrect in saying he had never met Edwards before Tuesday night. Edwards’ campaign provided a transcript of a prayer breakfast in February 2001 at which Cheney began his remarks by acknowledging Edwards. The two men also met when Edwards escorted Republican Sen. Elizabeth Dole to her swearing-in by Cheney in January 2003, a meeting the Edwards campaign emphasized by distributing news articles about the ceremony.

Democratic spokesmen also contended that when Cheney does visit the Senate, he meets only with Republicans and would not run into Edwards or any other Democrats.

Taxes, same-sex marriage

When the debate shifted to domestic policy, the men again clashed sharply.

Cheney repeated Republican charges that Kerry was a big-spending Massachusetts liberal, accusing him of voting for taxes 98 times. But he did not note that those votes included times when Kerry actually voted for lower taxes, just not as low as Republicans wanted.

Edwards laid out specifics in response, beginning by acknowledging that Kerry intended to “roll back tax cuts for people making more than $250,000 a year.” But he said that, contrary to Republican assertions, a Kerry administration would “keep tax cuts for people who make less than that.” And he promised additional tax cuts, which he did not quantify, to middle-class taxpayers for health care, college tuition and child care expenses.

“These families are struggling, and they need more tax relief, not less tax relief,” he said.

Cheney was then asked about a sensitive issue for him personally, a proposed constitutional amendment, backed by Bush, to outlaw same-sex marriage.

Cheney, whose daughter Mary is a lesbian, said he believed “it’s really no one’s business” what relations people enter into. Cheney acknowledged that he and Bush did not see eye-to-eye on same-sex relationships but said, “He sets policy for this administration, and I support the president.”

Edwards complimented Cheney for standing by his daughter and said he and Kerry agreed that marriage was between a man and a woman. But he said the difficulties gay couples faced had been politicized and that same-sex couples should be allowed to enjoy government and employment benefits like married couples.

Cheney declined to engage Edwards on the subject, simply thanking him for “his kind words about my family.”

Cheney declines an opening

Republican strategists had said Cheney would likely portray Edwards, who is completing his first term in the Senate, as a smooth-talking trial lawyer without much government experience.

But the vice president surprisingly passed on the opportunity when given the chance by Ifill. He chose instead to highlight his own long service in government, saying, “The president picked me because of my experience.”

Cheney’s refusal to go after Edwards on a personal level appeared designed to soften criticism that he relished the role of attack dog for the administration. A senior Republican signaled the plan before the debate, telling NBC News that the campaign hoped Cheney would come across as a teacher in contrast to the boyish Edwards.

It also threw Edwards off stride. Edwards, who was clearly primed to parry questions about his experience, could only awkwardly reply by saying Kerry would be tough on crime.

Making his tactic plain, Cheney again declined when Ifill pressed him to draw a distinction with Edwards. He said he thought there were more similarities than differences in their personal histories of achievement after impoverished childhoods, and he then returned to talking about the need to “go after the terrorists.”

To the same question about differences between the two, Edwards could only talk about the difficulty of stopping terrorists from coming into the country. He then rallied, acknowledging that he had little experience in government but adding, “What we know from this administration is that a long resumé does not equal good judgment.”

Ohio a battleground state

Ohio, where the debate was staged, is considered one of the top prizes in the election. With 20 electoral votes, it went to Bush by 3.6 percentage points in 2000.

Because of the stakes, both campaigns expected high viewership, which would be unusual for a vice presidential debate. In 2000, 46.5 million people watched the first presidential debate between Bush and Al Gore in 2000, before viewership plummeted to 28.5 million for the vice presidential session between Cheney and Sen. Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut.

Bush watched the debate from the White House residence before calling Cheney to congratulate him on his performance, said Taylor Gross, a spokesman for the White House.

Kerry watched from a hotel room in Englewood, Colo., where he is preparing for the second presidential debate. Kerry also called Edwards with congratulations, telling him as reporters watched, “The country tonight got a chance to feel the confidence that I had in you.”