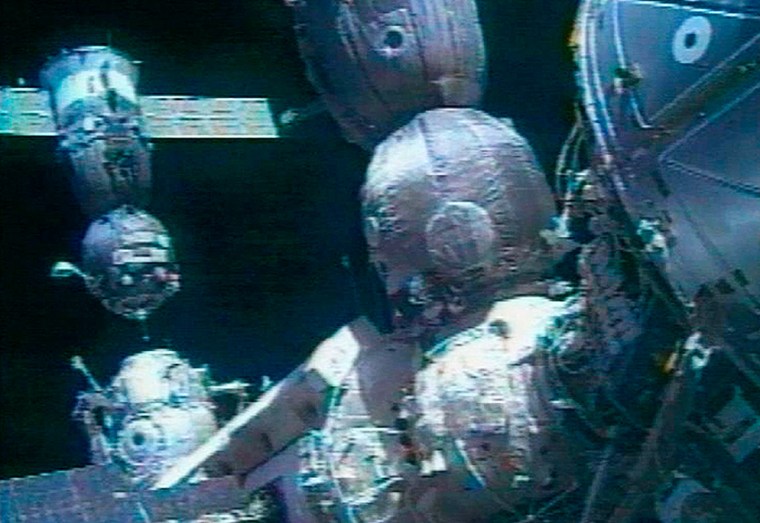

The docking of Russia's Soyuz spacecraft with the International Space Station has become a familiar sight for NASA.

Since the Columbia space shuttle disaster nearly two years ago, the Soyuz, the 30-year-old workhorse of the Soviet and Russian manned space programs, has been NASA's only ticket to space.

But when the shuttle program resumes sometime next year, the Soyuz is expected to remain a long-term solution to America's exploration of space.

"We'll end up probably with a mix of how we rotate the crews," said James Newman, director of NASA's programs in Russia and a four-time shuttle astronaut.

"One extreme is to rotate all the crews on the shuttle. The other extreme is to rotate all the crews on the Soyuz. Most likely, we'll end up with some combination of the two," Newman said.

Rethinking the shuttle

That NASA is entertaining dumping the shuttle as a crew rotation vehicle underscores the lasting problems of the accident-prone program. Designed primarily to deliver large payloads to space, the shuttle played a crucial role in the construction of the space station. But ferrying crews to the space station is costly.

Soyuz and the cash-strapped Russian space program offer an alternative. And the Russians won universal praise for offering expanded cooperation to NASA after the Columbia crashed in 2003.

"They have been there for us in this crisis," said James Oberg, a former NASA engineer and NBC space expert. "But you have to follow the money. The Russians aren't going to do this out of the goodness of their heart. They're making good money off the space industry."

Under an old deal, NASA gets free rides for American astronauts on Soyuz - twice a year - on Russia's regularly scheduled missions to the space station. But those tickets run out at the end of next year, and the agency faces difficulties in negotiating a new contract.

Tickets to space

Russia continues to sell seats to commercial passengers, at $20 million a trip. They are the same seats NASA envisions filling with astronauts.

The price tag is attractive to NASA, which spends many times more on each shuttle trip.

But under the Iran Non-proliferation Act of 2000, it's illegal for the agency to pay money to the Russian space program. The legislation seeks to punish the Kremlin for helping Iran build a nuclear power plant, but experts say Congress may have shot NASA in the foot.

"There's a major issue of funding and a major issue of partnership," says NBC's Oberg. "Even though we rely on the Russians more and more, by the end of next year they may not be there unless we find a way to pay."

"How much more risky will the world be if the Iranians have a nuclear weapon?" asked Rep. Dana Rohrabacher (R-Ca.), the chairman of the House Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics. "At the same time, we do need to cooperate with the Russians on our space endeavors.

Both NASA and Russian officials say they expect to continue their cooperation, most likely through barter or a "balance of contributions" to the space station. NASA also trains and flies Russian cosmonauts on space shuttle flights.

"Government to government, we seek to provide equal services to each other, which eliminates the needs for cash transfers," said Newman, NASA's representative in Russia.

Still, the political snag highlights NASA's reliance on the Russians.

Space on time

The Soyuz, in its third decade of service, is one of the most dependable delivery vehicles ever launched.

"The Russians get people into orbit, dock with the station, and bring them back. This is something they've been doing for 30 or 40 years. They haven't gone much beyond that, but that they do reliably. And at this time, that's what we need," said Oberg.

That reliability is influencing NASA's space plans after the shuttle is retired, probably in 2010.

"I think the lesson learned for us is that it is difficult to build a reusable space truck," Newman said. "We have had an amazing success. People worked very hard to make it safe. But in the future we ... will probably look at separating crew from cargo, as the Russians have."

NASA does not expect to have a functioning replacement for the shuttle until several years after it retires, leaving the agency even more reliant on the Russians to help the United States fulfill its obligations to the International Space Station.

"We see the Soyuz as part of the equation for rotating crews for the life of the space station," Newman said.