For most people, misplacing eyeglasses or losing the car keys is little more than a minor nuisance. For Amy Losak, it’s cause for anxiety.

"One day I left my glasses in the linen closet,” the New York public relations executive recalls. “I searched everywhere in my house for them, but didn’t find them until later when I was cleaning the closet. I totally didn’t remember putting them there.”

What ordinarily would be dismissed as simply absentmindedness made Losak, who is in her mid-40s, fearful that she might suffer her father's fate.

Losak's dad, Sam Rosenberg, had suffered from Alzheimer's disease for 14 years when he died at 93 last year. The experience of watching her beloved father slip away into a child-like state with only vague awareness of his family left Losak anxious about the "little black holes" of her own memory.

She says her forgetfulness "doesn’t interfere with my being able to do a job, but it’s annoying and, lately, frightening.”

Alzheimer's cases to soar

At a time when more Americans are living into their 80s and 90s than ever before, the fear of dementia, or "Alzheimer's anxiety," is rising and motivating many people to try to keep their brains sharp into old age.

Their fears aren't unfounded. Experts warn that a potentially devastating Alzheimer’s epidemic is looming.

There are 4.5 million people in the United States currently living with Alzheimer’s disease, and the number is expected to rise to as many as 16 million by 2050, according to the National Institutes of Health.

In a Gallup poll commissioned by the Alzheimer’s Association, one in three Americans said they knew someone with Alzheimer's and one in 10 said they had a family member with the disease.

“People understand that Alzheimer’s is a common illness and they’re very concerned about it,” says Dr. Marilyn Albert, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer's Disease Research Center and chair of the Alzheimer’s Association’s medical and scientific council.

'Is this it? Is it starting?'

Elizabeth Keihm’s mother was 73 when she died with Alzheimer’s two years ago. And because the disease runs in families, Keihm knows that statistically she faces a greater risk of developing it.

"There are days when I can’t find my keys or remember where I parked my car and I think, ‘Is this it? Is it starting?’” says Keihm, director of the Long Island Alzheimer’s Foundation.

“Once you’ve seen what this disease does, it changes everything,” she says.

To help reduce her odds of developing the disease, Keihm takes antioxidants, doesn't smoke cigarettes, goes on regular walks with her two dogs and tries to keep her brain busy with memory exercises.

"I do tricks like brushing my teeth with my other hand and take a different route to work so my brain doesn't get into ruts," she says.

"Every time you can't remember someone's name, you can really get yourself going about it," she says. "But you try to take all the steps you can."

Alzheimer's still a mystery

Doctors don't fully understand the causes of Alzheimer's — there are genetic and environmental risk factors — but they agree it's age-related.

More than 80 percent of cases are diagnosed after 70. And nearly half of people over 85 — the largest growing segment of the population in developed countries — suffer symptoms, according to the National Institutes of Health.

"There are more cases of Alzheimer's because more people are living to the age of risk," says Albert.

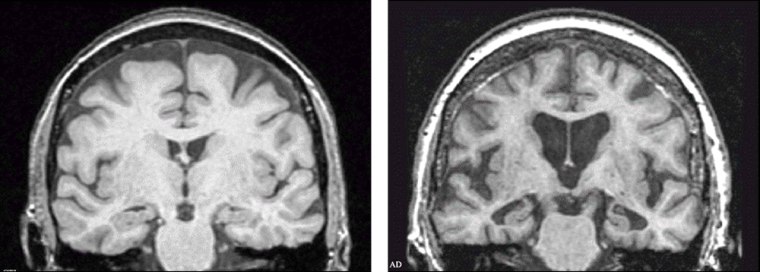

Scientists are pursuing the possibility that a cause of Alzheimer's is the buildup of toxic proteins in the brain. Clinical studies are focusing on blocking the accumulation of long tangles of beta amyloid and another protein in the brains of Alzheimer's patients.

Currently, five drugs are used to treat Alzheimer's, but they don't significantly slow the relentless mental decline in patients.

Pharmacologial treatments that can prevent or halt the progression of symptoms are years away. But many scientists agree that there are steps an individual can take to help ward off or at least delay symptoms of the degenerative brain disease, including exercising both the brain and the body, following a healthy diet and not smoking.

Slowing down the appearance of Alzheimer's symptoms in an individual by just a few years would be significant, says Dr. Steven Ferris, executive director of the Aging and Dementia Research Center at New York University.

The average age for the onset for symptoms is now 75. "If you can delay symptoms from emerging by only five years, then the average age would be 80 and you'd reduce by 50 percent the number of cases," because older people would die of other natural causes before they developed Alzheimer's, Ferris notes.

Researchers are increasingly studying normal memory loss in the hopes of understanding how Alzheimer's develops.

"Since brain aging is a risk factor for Alzheimer's, the more we can do to treat brain aging, the more effect we can have on Alzheimer's," says Ferris.