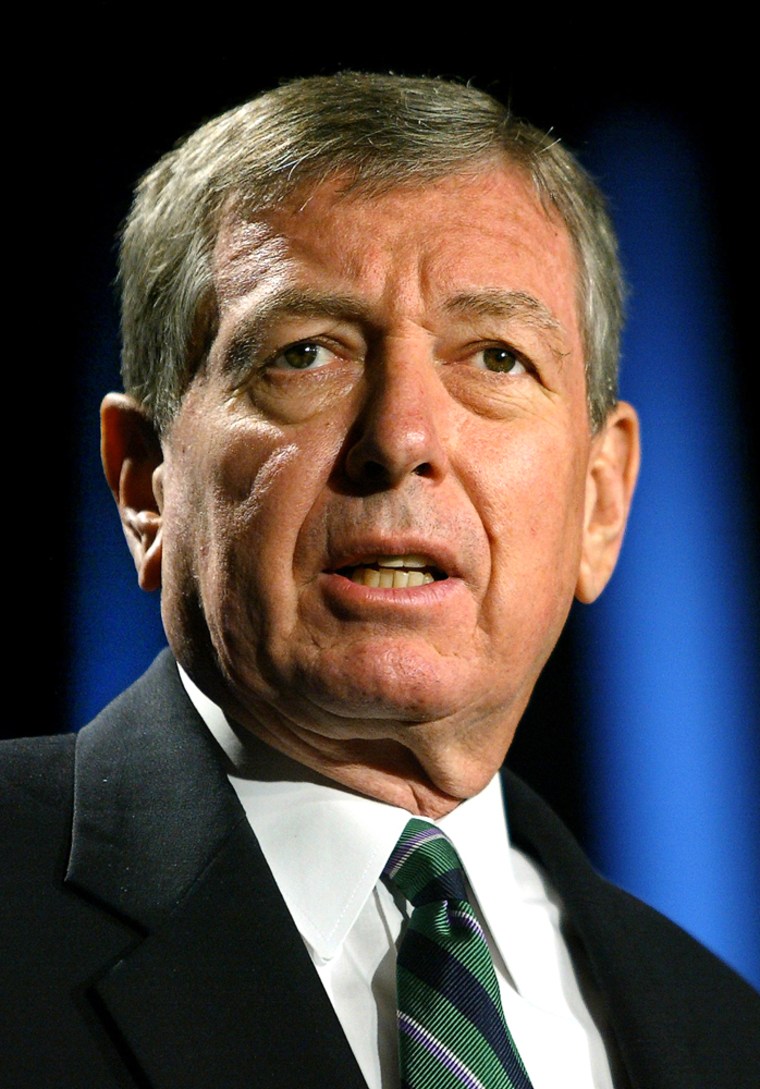

How will the first draft of history judge John Ashcroft, whose resignation as attorney general was announced Tuesday?

One way it will see him is as an earnest and ambitious politician who was elected Missouri governor and U.S. senator and tried to run for the 2000 GOP presidential nomination, but bowed out when it appeared George W. Bush would win it and when his own Senate seat seemed in jeopardy.

Ashcroft ended up losing his seat to Gov. Mel Carnahan, who died in a plane crash shortly before the 2000 election.

Ashcroft went on to survive a contentious Senate confirmation battle, the precursor of several such Senate scrapes he would have in his tenure as attorney general.

The USA Patriot Act, for which Ashcroft was often blamed, may be more accurately seen as a case of Democrats and a few Republicans, too, feeling remorse that they voted for it.

Soros blames Ashcroft

Finiancier and anti-Bush activist George Soros was only one of many who bashed Ashcroft, saying in a speech last summer: “Ashcroft passed the Patriot Act.”

In reality, Congress passed the Patriot Act, and President Bush signed it into law. The vote in the Senate was 96 to one, with Democratic presidential candidate Sen. John Kerry being one of the 96 “aye” votes.

Most of the alleged civil liberties violations with which Ashcroft was charged would have occurred in the first days after Sept. 11, 2001, when foreigners who had overstayed their visas were held without charges and without any hearings.

But Ashcroft surely had a knack for setting his adversaries’ teeth on edge.

In December of 2001, for instance, he accused his critics of “fear-mongering” and said, "To those who scare peace-loving people with phantoms of lost liberty, my message is this: Your tactics only aid terrorists for they erode our unity and diminish our resolve. They give ammunition to America's enemies and pause to America's friends.”

Laura Murphy, director of the American Civil Liberties Union Washington National Office, called his statement “a blatant attempt to stifle growing criticism of recent government policy” by “equating legitimate political dissent with something unpatriotic and un-American.”

Ashcroft was in some ways his own worst enemy — an austere and chilly personality, at least in public, who despite six years in the Senate didn’t seem to enjoy convivial friendships with his former Senate colleagues.

Surely it was never quite forgotten nor forgiven by Democrats that while a senator, Ashcroft had led a crusade to block some of President Clinton's judicial nominees and Surgeon General David Satcher. The Democrats’ animosity toward Ashcroft began long before the Patriot Act was ever written and thus the Senate hearing rooms were always filled with tension when he came up to Capitol Hill to testify.

Twisting their ears

One reason: Ashcroft seemed to relish giving his Democratic adversaries a partisan ear-twisting in some of his testimony.

For instance, last June when he appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee, he sketched out a theory of the broad powers of the president as commander in chief in time of war, arguing that no one could, or even should, say exactly where the president’s war powers end because the goal is national survival.

He cited as his authority one of his predecessors who served in a Democratic administration, Frank Murphy, Franklin D. Roosevelt's attorney general, whom FDR later appointed to the Supreme Court.

Ashcroft approvingly quoted from a memo Murphy wrote in 1939 saying the constitutional powers of the president in time of war “have never been specifically defined and, in fact, cannot be — since their extent and limitations are largely dependent on conditions and circumstances.”

Ashcroft praised Murphy as “an attorney general whose respect for and familiarity with law was so profoundly understood that he became a member of the U.S. Supreme Court” — making one wonder if that was where Ashcroft, too, hoped to end up.

Ashcroft rebuffed a demand from Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass., that he hand over memos dealing with the question of whether the president’s powers might include the power to order use of torture in interrogating al-Qaida suspects.

Ashcroft rejected the idea that anything done by Bush or the Justice Department “has directly resulted in the kind of atrocities which were cited. That is false.” The Abu Ghraib abuses were not done “pursuant to any order, directive or policy of this administration,” he said.

Citing Bobby Kennedy

On another occasion — again showing his penchant for using Democratic attorneys general to vindicate him — Ashcroft cited Kennedy’s late brother, Robert Kennedy, who as attorney general in 1961 said he’d prosecute Mafiosi if they so much as spat on the sidewalk. Ashcroft promised to do likewise to terrorists by using even minor infractions of federal law as basis for prosecution.

Out on the campaign trail in Iowa and New Hampshire last year and this year, Ashcroft was truly hated by the Democratic activists, perhaps more so than Bush himself. The Democratic presidential contenders made a point of including an anti-Ashcroft blast in nearly every debate.

Democrats also suspected Ashcroft of playing politics when in May he announced that terrorists would try to attack the United States in the next few months.

“The Madrid railway bombings were perceived by Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida to have advanced their cause,” he said, referring to the March 11 bombing which killed nearly 200 and led to the defeat of the candidate supported by U.S. ally former Prime Minister Jose Maria Aznar.

“Al-Qaida may perceive that a large-scale attack in the United States this summer or fall would lead to similar consequences,” Ashcroft predicted.

But despite the Democratic criticism of Ashcroft, Viet Dinh, who served as assistant attorney general under Ashcroft until last summer, said late Tuesday, “He led the department in a very, very difficult time and withstood a lot of criticism and despite that criticism, he has remained steadfast and his mission remained clear. That’s why he was such an effective leader of change and a powerful attorney general.”

Dinh added, "Of course there have been mistakes made in specific prosecutions. But when those mistakes were uncovered it is another great mark of John Ashcroft's leadership that he doesn't try to paper it over, or to spin it away politically. In the case of the Detroit (terrorist) prosecutions he came into the court after a full and fair investigation by the Department of Justice and confessed error. He said, ‘We had prosecutors who exceeded the bounds of their authority and who have potentially violated the constitutional rights of the defendants. We hereby drop all the prosecutions and we will see what charges we can bring in a legal constitutional manner.’”