Yasser Arafat promised Palestinians he would return them to the homes they lost when Israel was founded in 1948. He never delivered, and now many refugees wonder whether anyone can.

Arafat, whose name became synonymous with the Palestinian cause in the four decades he led his people, “was the only one with the stature to wrest that right,” said Ashraf Majzoub, a refugee from the Israeli seaside town of Acre.

“We fear that whoever will succeed him will strike a deal with Israel for a Palestinian state to which we won’t even be allowed to go,” he added. “Then the whole world will forget about us.”

From their squalid camps, the refugees have anxiously followed radio and TV bulletins on Arafat’s health in the 12 days since the Palestinian leader was taken to France for medical treatment. Fresh pictures of Arafat have gone up on walls. A few refugees marched in small, spontaneous demonstrations in support of the man they affectionately called Abu Ammar, his nom de guerre. His opponents refrained from criticizing him.

‘A great, historic figure’

“Despite our differences with him, we consider him a great, historic figure,” said Ziad Nakhaleh, a Damascus-based member of the Islamic Jihad group, which had been at odds with Arafat.

“Abu Ammar was a man who was adored by his people because he was always close to the people and cared to solve their problems,” said Awni Shatarat, 41, owner of a boutique in Jordan’s Baqaa Camp, 17 miles northwest of the Jordanian capital, Amman.

“He did not take advantage of the Palestinian cause,” he added. “He had no farms and no palaces like other Arab leaders.”

The return of the refugees has been one of the thorniest issues facing Palestinian and Israeli negotiators since the 1993 peace agreement that created the Palestinian Authority in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank and Arafat’s return to Palestinian territories in 1994.

The last offer of statehood, in a peace plan put forward by President Clinton in December 2000, would have allowed the refugees to settle in a state in the West Bank and Gaza if they gave up the demand to return to Israel proper. But negotiations died in the Palestinian-Israeli fighting that had broken out the previous September.

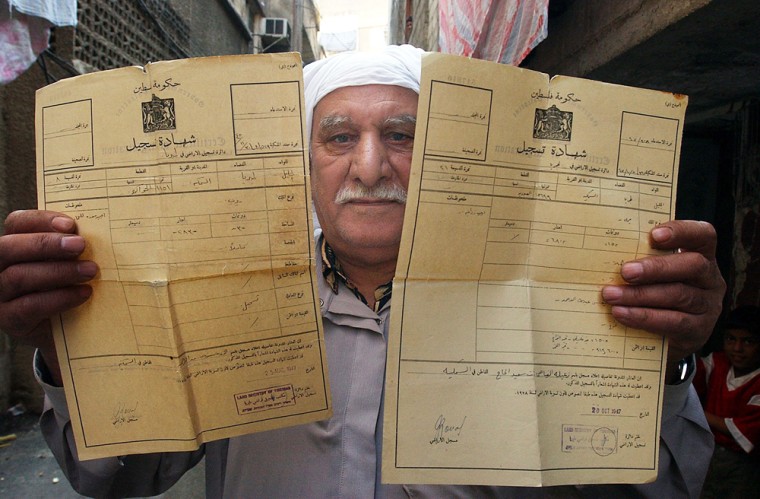

Still, the refugees have tenaciously clung to the “right of return” to the places where they, their parents or grandparents were born. Those born in refugee camps call Palestine home even though their villages may no longer exist or are now populated by Israelis.

A tough lot for refugees in Lebanon

There are more than 4 million refugees in the West bank and Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. Although they all face an uncertain future, life is especially tough for the 350,000 living in Lebanon’s 12 camps.

Unlike Jordan, Lebanon denies them citizenship. Unlike in Syria, most jobs are off-limits to them.

The Lebanese government doesn’t want them to become citizens since the Palestinians, mostly Muslims, would upset the religious balance.

Hundreds of Palestinians were massacred in the Beirut refugee camps of Sabra and Chatilla in 1982 by a Lebanese militia allied with Israel.

Despite squalor and overcrowding in the camps, Palestinians say Arafat is not to blame for his inability to realize their dream. Some fault Arab states for not standing by them while others say Israel is responsible.

“President Arafat went through pains for the Palestinian people and for the Palestinian cause, but he couldn’t accomplish much over the years because of Israeli stubbornness,” said Sayed Abul-Kheir, 35, a Gaza Strip native.

Dream of return remains alive

Mahmoud al-Haj Hussein Tarakhan, from a village in Israel, said the “right of return will remain there because these lands are ours, they belonged to our grandfathers.”

“Arafat is the symbol of the revolution and even with him gone, our rights remain,” said the retired civil servant, speaking from Hussein Camp in Amman.

Majzoub, the man from Acre, said Arafat’s apparently imminent death has “devastated me more than my brother’s death.”

“My brother taught me things related to the family, but Abu Ammar taught us to be brave, steadfast and patient,” he said.

Majzoub, a tall, slim man of 36, recalled Arafat visiting his Chatilla camp when he was 9.

“I will always remember his big smile,” said Majzoub. “And I will always remember his words: ’You are the future. It’s cubs like you who will liberate Palestine.”’