The promotional video shows a multi-jointed titanium handyman untwisting knobs and disconnecting an electrical cable with slow-motion aplomb, displaying fine motor skills that the voice-over assures will enable it to install "new batteries, gyroscopes and scientific instruments" aboard the aging Hubble Space Telescope.

But the video is only a teaser. In April, when NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt showed the whole sequence to headquarters VIPs, what had first seemed an elusive dream -- a robotic mission to service Hubble and extend its life by five years or more -- suddenly became real.

"I remember coming to look at this stuff and asking, 'Is that an [animation]?' And somebody said, 'No, it's really happening,' " recalled Edward J. Weiler, who was NASA's associate administrator for space science at the time and is now Goddard's director. "I didn't think robots could do this kind of stuff."

It is by no means a sure thing. Yet largely because of the Canadian robot named "Dextre," NASA has gone in less than a year from virtually writing off the Hubble to embracing a mission that will cost between $1 billion and $1.6 billion and approach in complexity the hardest jobs the agency has ever undertaken.

"Almost as difficult as landing on Mars successfully twice," Weiler called it. Servicing the Hubble, like the nine-month tour de force that has kept two rovers tooling around the Martian countryside, will demand a host of technical tasks and tricks that have never been tried.

How the Hubble can be saved

To do it, the United States must develop its first-ever robotic docking vehicle, fill a bag with tools that, in many cases, have not been invented, and use the robot repairman to unscrew j-hooks, open and shut doors and "drawers," disconnect and attach electric connectors, and rig jumper cables.

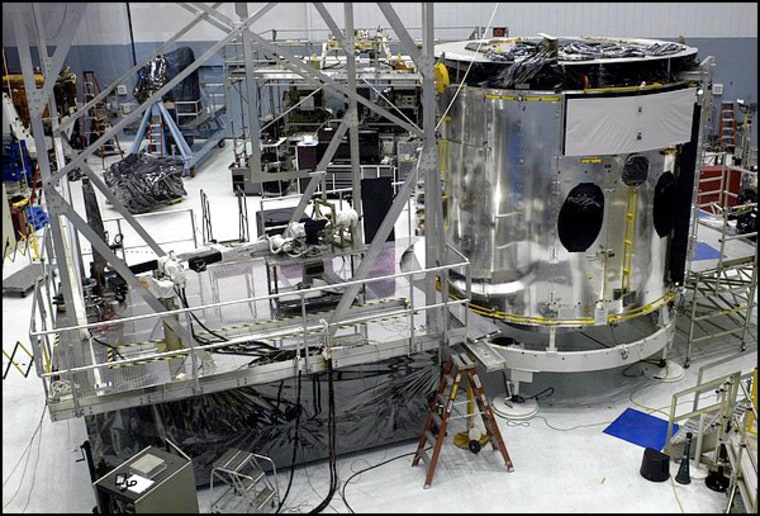

By the end of 2007, NASA hopes to put into orbit its Hubble Robotic Vehicle of four components: a de-orbit module designed to dock with Hubble; a grappling arm to seize the telescope during docking and serve as a repair platform; an ejection module to carry spare parts and tools; and Dextre.

The jobs, in descending order of importance, are to change Hubble's batteries; install new gyroscopes; swap an old camera for a new, more sophisticated one; install a new spectrograph; and, if possible, replace a telescope pointing device and repair another spectrograph.

"There's nothing easy about it. It's all firsts," said Goddard's Preston M. Burch, Hubble's program manager. "And some of the things we're thinking about make people nervous." The fundamental tenet for a servicing mission, he noted, is the same one that doctors espouse: "Above all, do no harm."

In the past, shuttle astronauts had the job of servicing Hubble, missions that required a few days of spacewalks lasting six hours each. Dextre "can work 24-7," Weiler said -- a fortunate feature, because robots are not as supple as humans. "Watching it is like watching grass grow," Weiler said.

Burch hopes to complete the mission in a month. Some of it will be done by the robot working on its own, but most will be handled by ground controllers manipulating the robot's two arms -- like playing a video game.

"Astronauts are keen to do this," Burch said, and they will probably get the call because of their experience and knowledge of the perils inherent in handling large objects in space -- where something pushed or pulled does not slow down until it is checked.

"Hey, if they ask me, I would be very happy to do this," said Michael Massimino, an astronaut who serviced the Hubble in 2002 and has joysticked Dextre in the lab. "It's an interesting and challenging project -- it's cool, really cool."

A robotic repairman

Dextre, so nicknamed by the Canadian Space Agency, was developed by MD Robotics, of Brampton, Ontario, as the Special Purpose Dextrous Manipulator, a robotic repairman destined for eventual duty on the international space station.

Dextre has a central "torso" with two 10-foot arms that can pivot, turn, reach and grab in seven different ways. In repose, it is a 2,220-pound, Rube Goldberg-style titanium stick figure, but in action it can readily choose a mix of intricate movements to execute the commands of its operator.

Dextre's future changed dramatically in January, after NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe canceled a scheduled shuttle servicing mission to Hubble, citing safety concerns after last year's Columbia tragedy.

Public outrage greeted this decision, which essentially sentenced Hubble to a watery grave once its batteries give out, but O'Keefe left open the possibility of robotic repair, and NASA sent out a bulletin asking for proposals.

Burch, who oversees Hubble from Goddard's Greenbelt labs, said the cancellation did not come as a surprise: "We knew it was going to be a long time before a shuttle mission, and if that day never came, what could we do?"

MD Robotics responded to the bulletin, and Goddard asked to see Dextre perform. "We were able to demonstrate a lot that astronauts had done," said Dan King, MD Robotics' director for orbital robotics. "We opened doors, gained access, changed an existing connector, that kind of thing."

After Goddard and MD Robotics engineers dazzled the NASA brass in last April's demonstration, excitement started to build, climaxing in August, when O'Keefe traveled to Goddard to tell the Hubble team to get to work on a robotic mission to fly by the end of 2007.

Preliminary plans in place

Late last month, NASA awarded MD Robotics a $144 million preliminary contract to provide Dextre and the grappling arm, and gave a $330.6 million contract to Lockheed Martin for the de-orbit module. Goddard will build the ejection module and assemble the package, which will weigh about 24,000 pounds, fully fueled.

NASA set 2007 as the deadline, at first suggesting that Hubble's batteries would give out by then and cause the telescope to shut down within hours. But Weiler said a second set of test batteries on the ground show that Hubble's power should last until 2009. Still, engineers are sticking with an early launch in case the schedule slips.

Each of the contemplated jobs is complicated but doable, Massimino said. "The main thing is to move very slowly." There is a time lag of 1.5 seconds between the command sent by the operator on the ground and Dextre's ability to execute it as it orbits with Hubble 360 miles above the Earth, but Massimino said he and another astronaut were able to handle the delay "pretty well" during a recent practice run, "as long as we took our time."

The Hubble Robotic Vehicle will be built from scratch, giving the United States a robotic rendezvous and docking capability for the first time in the history of space travel.

The spacecraft will use the 39-foot grappling arm to grab Hubble, then swing down until the de-orbit module can lock to the telescope's underside. Executing this maneuver -- which is routine for the shuttle -- will require precision sensors that Lockheed Martin must develop.

The de-orbit module will have six new batteries inside and will feed power to the telescope through the same "umbilical" cable that the shuttle used, an arrangement that will survive for the rest of Hubble's life. The robot will jettison the tool-carrying ejection module at the end of the servicing mission, but the de-orbit module will stay with Hubble until the end, eventually steering it into the sea.

The trouble with the new alignment is that power can only move in one direction, so the batteries cannot be recharged through the umbilical cable. Instead, Dextre will rig jumper cables from the telescope's solar arrays to the batteries.

Next, Dextre will unlatch the fastener holding Hubble's Wide-Field and Planetary Camera 2 in place and remove it from the telescope, like pulling out a drawer. Wide Field Camera 3, one of four imaging instruments on the telescope, will then be inserted to replace it.

This would also be a relatively straightforward task, except engineers will attach six new gyroscopes to the camera, thus avoiding the hazards involved with opening the difficult-to-handle doors that guard the compartment where the original gyros are mounted.

To make it work, Dextre will have to run a cable from the new gyroscopes out the compartment door, back to control units in the de-orbit module, then up to the telescope's computer, so Hubble can receive the information it needs to aim the telescope and stay stable in space.

Next comes the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph, another swap-out requiring Dextre to disconnect and reconnect four electrical cables. After that, Burch would like to have it install a new Fine Guidance Sensor, a pointing device, and he has also asked for ideas on robotic repair of the nonfunctioning Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph.

"The concern of headquarters" is that "these crazy people at Goddard" want to do too much, Burch acknowledged. "And it's true, we don't want to lose sight of the main objectives."