In the last couple years, photography has become the “killer app” of digital technology. Online sharing of photos has become the preferred method of visual communication, whether through e-mail attachments to friends and family, photo albums at internet storage and printing sites, or on Web sites themselves. But what if you want to go to the farthest end of the earth – say, a village in the highlands of New Guinea – and share your experience with the world, as it’s happening? That’s the challenge facing us in Digital Village: New Guinea.

Making a visual record of travel is at least as old as Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, when he brought along artist Vivant Denon to document the cultural riches of the Pharaohs. Carlton Watkins’s photos of Yosemite from the 1860s, and Edward S. Curtis’s imagery of North American Indians from the turn of the century, are examples of how photographs helped shape our country’s view of its natural scenic resources and its native populations. Taking the power of photography into the digital age, and to the most remote places on earth, is the next step.

Travel and photography

With the democratization of photography, spearhead by the popularity of the Eastman Kodak Brownie camera (first introduced in 1900), travel and photography came to fit together naturally, as a way for others to share the visual spectacle and personal discoveries of the strange and new. For the much of the past century it’s been virtually inconceivable to go anywhere without a camera, and the proverbial family photo album (or slide show) is often the easiest way to share the vacation experience.

But nowadays that camera is often digital, and that photo album is online. By the end of the year up to half of Internet-connected homes will have digital cameras, about 20 percent of U.S. households according to industry analysts. Even Kodak is re-forging its traditionally film-based business to focus on digital imaging. Not only technology, but sheer economics drive this evolution: The cost of a digital SLR camera (Single Lens Reflex, the standard for professional and prosumer photographers) has plummeted from about $12,000 in 1995 to less than $900 today. And the amateur photographer is finding plenty of options for under two hundred bucks.

Cameras as small as a deck of cards are capable of taking hundreds of photos of 8 by 10-inch print quality, without the use of physical film stock, chemicals or special darkroom equipment. Today a 3-megapixel point-and-shoot can sell for as low as $129. One drug store chain, CVS Pharmacy, will soon be offering a disposable digital camera that includes a review screen and the ability to delete unwanted images, all for $19.99 — you get prints made from the camera at the store, or a CD to take home and view on your computer. (Don’t have a computer yet? What are you doing reading this article?)

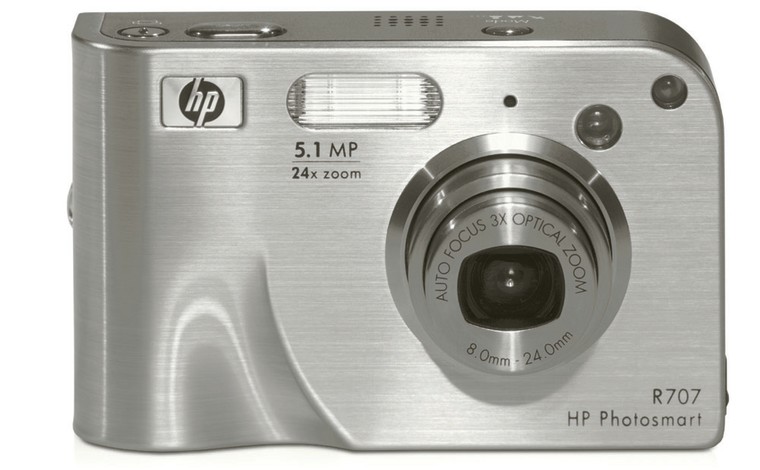

Hewlett-Packard, which is sponsoring this project, is contributing two of their consumer-model digital cameras for use throughout our expedition, and at the “digital village” itself. The HP Photosmart R707 is an advanced consumer digital camera with multiple automatic shooting modes, in-camera red-eye removal and other technologies that make it “hard to take a bad picture,” according to HP. It produces a 5.1 megapixel image, and includes 32 MB of internal storage so you can take photos even without the “flash memory” SD/MMC (secure digital multimedia card) that can be inserted.

The HP Photosmart M307 is a smaller, lighter version of the R707, with many in-camera automatic modes and controls in a simple, user-friendly layout. Its photos are 3.2 megapixels, and its internal memory 16 MB (and again it has a SD/MMC slot). Both cameras include LCD screens to preview the image as a viewfinder screen, which doubles as a review screen to check the shot once it’s taken – a standard feature on most digital cameras. It’s our hope that both of these cameras will be so easy to use that the villagers in highlands New Guinea will quickly adapt to seeing the world through the lens — or the viewfinder — and be able to share their perspective on their lives, their families, their village (and their visitors) with the world.

The final piece of the puzzle for the consumer digital photographer is making prints. A number of online websites allow uploading and storage of digital photos, which can be arranged into albums and even “communities,” but the business model for these is selling prints of the pictures. You send your mother to an album of your baby’s first steps, she finds one she likes, orders prints, and voila — Grandma has a visual souvenir of the milestone for her scrapbook.

But increasingly, dedicated photo printers are coming on market that let you create high-quality color prints at home, without going online (or going to the drug store).

HP’s entry is the Photosmart 375, (image) which the New York Times said was “so small, white and cute, you might mistake it for Barbie's First Toaster.” It’s also a powerful little unit, accommodating most memory cards for PC or Mac, can run on batteries for increased portability, and includes a small 2.5 inch TV screen to select the image you want to print. The fade-resistant full-color prints are 4" by 6" and print out in about a minute.

Digital expeditions on the Web

But for international travelers there are downsides to shooting digital. How do you store the pictures? How do you display them? And what happens when the batteries run out? Storage and power are the main bugaboos for the digital photographer, and for the photojournalist or expedition shooter — far from home, traveling light, off the grid — these problems can become overpowering.

For the Digital Village: New Guinea project, we are faced with all these issues, as well as a final challenge: getting the images from the field to the Internet. We turn to another advancement of the modern age, the communications satellite. In the early 1990s Inmarsat, the International Maritime Satellite system, launched a network of four satellites in geo-synchronous orbit, allowing overlapping coverage of almost the entire globe (except polar regions). This means with a sat-phone you can call almost anyplace on earth wireless; with digital I/O (input/output) connections you can use the sat-phone as you would any modem, and transmit data. Internet expeditions since the mid-1990s have relied on this technology to keep Web users connected to exotic travel, and they still do, using updated satellites and dedicated modems for digital use, such as the Inmarsat R-Bgan.

Visual Anthropology

Turning the camera around has become a stock-in-trade technique of field researchers over the past 40 years, in the discipline known as visual anthropology. In 1966, a small team led by Sol Worth and John Adair let Navajo Indians in Pinetree, Ariz. take control of the cameras and make short films about their lives. The result, “Through Navajo Eyes,” is the seminal classic of the genre, a book detailing the project and its resulting seven short films. Many other anthropologists since have let their subjects either shoot video or stills, as a way to see through the eyes of others. (A good website to explore this discipline is the Society for Visual Anthropology.)

Visual anthropologists are interested in all aspects of culture, including art, architecture and artifacts as well as behavior, seeing all as forms of visual communication. Still photography, video, painting and other images can be used to evaluate and interpret a culture. When the study group themselves — a community of any sort — participates in the creation of the visual record, a wealth of information and understanding can be gained.

This is what we hope to accomplish with Digital Village: New Guinea — to let the people we visit show us images of what they see, the world through their eyes.