When Attorney General John Ashcroft announced his resignation this month, reporters and editors let out a silent cheer in newsrooms across America, for reasons that had nothing to do with any political opinions they might hold. They cheered because Ashcroft, who hoarded access to government information with the zeal of a religious convert, made their jobs much harder.

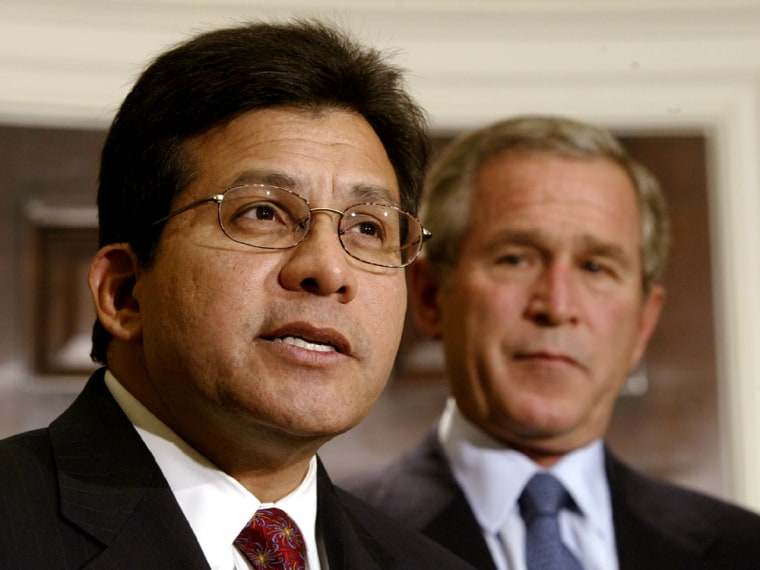

The nomination of White House counsel Alberto Gonzales to succeed him, however, holds out little hope for improvement, press and watchdog groups say.

“There’s a lot we don’t know about his actions as White House counsel and his advice to the president,” said Steven Aftergood, director of the Project on Government Secrecy of the Federation of American Scientists. “What we do know is rather discouraging.”

As attorney general, Gonzales would inherit Ashcroft’s role as caretaker of the 1966 Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA, and the right of the public to know what its government is doing.

Ashcroft hobbled many journalists — as well as scholars and business researchers — in 2001 when he issued guidelines laying out a legal case for restricting release of public documents under FOIA. He advised agencies to look for a “sound legal basis” to withhold documents, with the promise that the Justice Department would back them in court.

While there was no indication that Gonzales played a role in developing Ashcroft’s memo, “there is also no indication that he disagreed with it,” the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press said this week in a . In fact, as White House counsel, the committee said, he has shown “a penchant for strictly regulating access to government and executive-branch information.”

Fox in the henhouse?

The reporters committee accused Gonzales of pursuing a policy it called “quasi-executive privilege ... so named because the privilege’s breadth, as defined by the Bush administration, is much greater than what is commonly known by lawyers as the executive privilege.”

The policy has been used to delay or bar release of information not only to the public, but also to Congress, most notably in the investigation of the torture of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib and in the work of the commission Bush appointed to investigate the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

In both cases, the reporters committee said, Gonzales was a key player in trying to keep information under wraps. He argued in March that to compel national security adviser Condoleezza Rice to testify under oath before the Sept. 11 commission would limit the freedom of President Bush’s advisers to give him candid advice.

In another high-profile dispute, Gonzales delayed releasing 60,000 pages of papers at the Ronald Reagan Library and Museum for months, long enough for Bush to issue an executive order in November 2001 allowing former presidents to bar the release of specific documents by claiming executive privilege years or even decades after the fact.

“In some cases, the release of documents could jeopardize our national security, and, while the pursuit of history is invaluable to our society, it should not endanger American lives,” Gonzales wrote in an article for The Washington Post in December of that year. “Nor should it deprive a president of candid advice while making crucial decisions.”

The Cheney records

Gonzales’ longest-running battle has been over his insistence that the public has no right to know what happened in meetings of Vice President Dick Cheney’s task force reviewing U.S. energy policy. Opposition to the policy led to a lawsuit that brought together activists on opposite ends of the political spectrum: the environmentalist Sierra Club and Judicial Watch, the conservative public policy group that hounded President Bill Clinton throughout his administration.

The Supreme Court declined to order that the records be made public. It sent the case back to a lower court, where it remains undecided.

“God only knows how long it will take,” David Bookbinder, Washington legal director of the Sierra Club, told MNSBC.com’s Tom Curry when the ruling was issued in June.

Speaking in July 2001 about his reluctance to disseminate records of the government’s proceedings even to federal investigators, Gonzales said: “Congress has an obligation of oversight. [But] we believe it’s legitimate for this administration to keep certain information confidential to allow the executive branch to do its job.”

The Bush White House has also expanded government use of formal classification to keep information secret. In December 2001, the White House granted the right to classify documents to the secretary of health and human services. The administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency got the same power in May 2002, followed by the secretary of agriculture in September 2002.

Cause for optimism?

The president’s chief lawyer for all those decisions was Gonzales, advocates for government openness noted.

“You have to remember [that] in my current job, I am an advocate for a client who has an agenda,” Gonzales said in a 2003 interview with The Houston Chronicle. “So there may be some things the president wants that I personally disagree with.”

Aftergood said that he thought “the distinction is a valid one on principle” and that “if one is looking for encouraging signs, one could draw some confidence from that.”

“I hope also that he will be asked some probing questions during his confirmation about his attitudes toward freedom of information, public accountability [and] congressional oversight,” Aftergood said.

“When government is permitted to operate behind closed doors, it is easier for it to conceal its errors and not to learn from experience,” he said.