A pocket of near-Earth space tucked between radiation belts gets flooded with charged particles during massive solar storms, shattering the illusion it was a safe place for satellites.

The safe zone was thought to be virtually radiation-free, a good region in which to deploy satellites so they'd be protected from the potentially debilitating effects of magnetic storms that can slam into Earth at millions of miles per hour.

But a new study of a string of severe storms last year debunks the notion. Scientists discussed the work here Wednesday at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

The once-suspected safe zone is called the Van Allen Radiation Belt Slot. The Van Allen belts are like two doughnuts of electrons around Earth, all trapped by the planet's magnetic field. The safe zone is a thick circular ribbon of space between the two doughnuts, from about 4,350 miles (7,000 kilometers) above the planet to 8,110 miles (13,000 kilometers) up.

NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, parent of the National Weather Service, have recently pondered putting satellites into this region to avoid the radiation that affects satellites at higher and lower altitudes. (In most cases, however, satellite location is determined by imaging or communication needs.)

Solar Halloween tricks

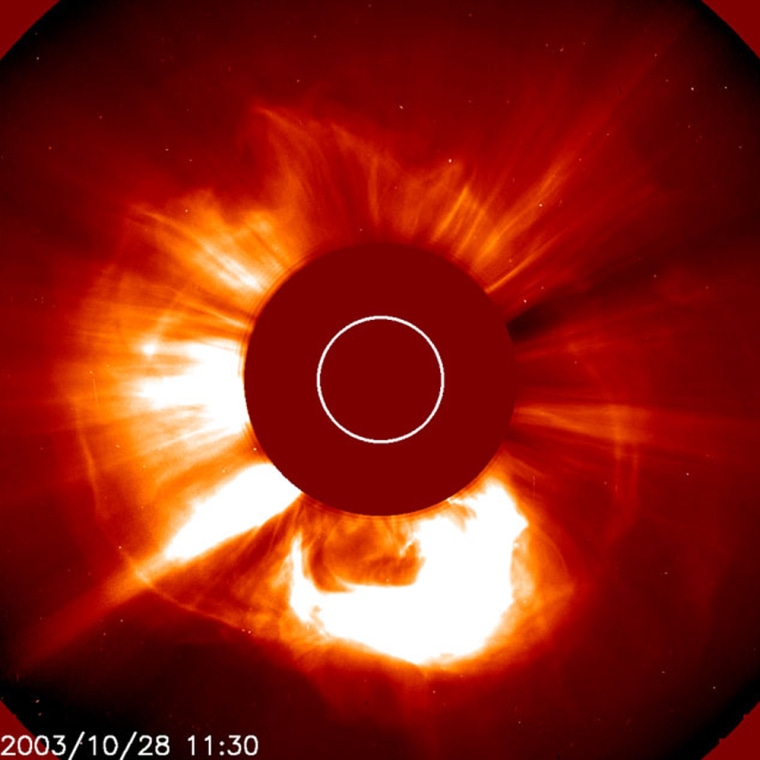

Scientists knew some radiation occasionally leaked into the slot, but it was observed to dissipate quickly. The Halloween storms of 2003 bathed the slot with hot gas called plasma that persisted at extremely high levels for two weeks, and dangerous levels that lasted more than a month, said study leader Daniel Baker of the University of Colorado at Boulder. A lingering infusion of charged particles remains in the slot today, more than a year after the storms.

The structure is a new and presumably temporary radiation belt.

"The normal safe zone suddenly and dramatically became a hot zone," Baker said. "It became the hottest region in Earth's magnetosphere."

The magnetosphere is an outer protective shell created by magnetic field lines, which are generated deep inside Earth and radiate out from the poles. If you could see the structure, it would look something like a giant wire-frame pumpkin.

The slot was breached because the intense storms eroded and shrunk Earth's plasmasphere, a protective bubble that usually surrounds the safe zone. The plasmasphere is full of relatively cold plasma, around 10,000 degrees Celsius. With the plasmasphere blown away, the safe zone filled with plasma thousands of times hotter and more energetic. The energetic particles can damage or disable a spacecraft's electrical system.

Strongest storm on record

The series of storms in late October and early November 2003 was unlike anything witnessed in modern times. Within two weeks, the sun kicked up 10 solar flares classified as major, including one that reached at least X28 -- the highest ranking ever given to a solar tempest since satellites have been monitoring them.

Solar flares are intense flashes of X-rays and other radiation that reach Earth in a matter of minutes, travelling at light-speed, and can knock out radio communications. Worse are the clouds of charged particles, known as coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, that typically accompany flares. CMEs arrive anywhere from about 18 hours to two days after a flare.

The series of CMEs around Halloween in 2003 claimed several casualties, disabling two Japanese satellites above Earth and knocking out a radiation-monitoring instrument on a Mars-orbiting satellite. It stressed and squashed the magnetic field of this planet and others. This year the fastest of the storms was detected by the Voyager spacecraft at the very edge of the solar system.

On Earth, radio frequencies suffered, including communications between airline pilots and ground control, and a power outage in Sweden was attributed to the storms. Passenger jets were rerouted during the more intense events to avoid extra doses of radiation at high altitudes above the polar regions.

Particles stripped

As the storms slid past Earth, they interacted with the planet's magnetosphere and essentially created a giant electric motor, explained Jerry Goldstein of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Particles in the protective plasmasphere were stripped out of the larger magnetosphere and lost to space, Goldstein said.

The unprecedented solar bout contributed to the problem, weakening the system with each successive punch. Some of the storms moved more quickly than ever measured, up to 6 million mph (2,700 kilometers per second), and that was a factor too, Baker said. Finally, some of the storms had a magnetic orientation opposite to that of Earth, which other research has shown can open cracks in the magnetosphere, allowing the storm to pummel the inner layers of Earth's protective setup.

"It's like opening a gate," Baker said.

The observations were made by NASA's Solar, Anomalous and Magnetospheric Particle Explorer satellite, or SAMPEX, which flies through the Van Allen belts. The research is detailed in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature.

The results will help mission planners who might decide to put satellites into the still-sometimes safe zone, said Terrance Onsager of NOAA's Space Environmental Laboratories. Radiation shielding can be added to satellites, Onsager explained, but it is expensive, so it's important to know how much protection to add.