The true power of digital photography never really hit me until I came face to face with the dashing young Australian grandfather I had never met -- on my 21-inch computer screen.

A home scanner, coupled with a cheap photo-editing program, allowed me to blow up the few tiny images of him my family had saved so I could get my first close look at his melancholy face.

The encounter highlighted for me the magnitude of change digital technology is ushering into the 165-year-old photography industry, creating turmoil and excitement as people buy digital cameras at rates far exceeding industry projections.

This past year, people in the United States bought twice as many digital cameras as film models, according to the Photo Marketing Association. Next year a bigger change may loom: Cell phone cameras are projected to sell even more than regular digital cameras.

The larger story, though, is how people are using their digital cameras differently from the film models. Consider the photos snapped by National Guardsmen showing abuse of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison, which were e-mailed widely and shown on national TV. Or the Nashville man who helped police nab the mugger who jumped him at a carwash, by using his cell phone camera to photograph the mugger as he fled.

At home, consumers are embracing all kinds of new camera accessories, and older tools once reserved for professionals -- flatbed scanners, photo-editing software, desktop publishing programs -- to do things that were impractical or impossible in the era of film.

Many of these changes hit home when I decided to digitize every document I could find about my mother's father.

Never-seen details

His story had been tucked away for decades in a red velvet portfolio my grandmother kept in the attic. Tattered yellow clippings from British tabloids told the tale:

John Holmes, a celebrated Australian rugby player, met and married my British grandmother, Mary Shore, in 1929 when the Australian team played Britain in the Yorkshire town of Ilkley.

The London press had a field day. "Ilkley Girl's Romance," shrieked one headline. " 'Ah, you thief,' was how the Prime Minister greeted Holmes when he received the [team] at 10 Downing Street yesterday . . ." the article said. "You boys really mustn't take all our nice girls."

I had read the stories when I was young, but as the clippings became too brittle to handle, the details faded from memory. When my grandmother died in 1999, more than a decade after my mother, I inherited the folder, which sat in a drawer until a few months ago when I purchased a $99 scanner at Sam's Club.

I bought the scanner as I began to learn how much you can do with photos once they are in digital form -- clean them up, lighten dark areas, blow up small sections and inspect details you might otherwise never see in a 4-by-6-inch print -- all using entry-level photo software. I had bought my first digital camera in 1998 and have taken thousands of photos since then, driving people crazy by aiming the shutter at them at five to 10 times the rate I did when I had to pay to develop film.

In the past two years I slowly moved from capturing images to exploring the many things I could do with them.

I decided it was time to scan in my family's aging paper documents -- not only to preserve them for future generations, but to share them the way I share photos, by e-mailing and posting them online. I pulled out my grandmother's portfolio and started scanning her faded newspaper clippings into my computer. Though my scanner was cheap, it captures images in super-high optical resolution -- up to 3,200 dots per inch by 6,400 dots per inch. Why does resolution matter? Because the more dots per inch a scanner can capture, the bigger you can blow up the images it creates without losing clarity.

I opened the scanned image of the first article in my editing software, cropped it to display only the image of John Holmes, brightened and sharpened it, then used the "zoom" button to fill my entire screen with his face.

There, for the first time, I got a really good look at this man who had died two decades before I was born. As I inspected the big floppy ears that looked suspiciously like mine, I understood for the first time the power digital imaging has to affect our perceptions of life, in part by adding detail and texture to the stories we develop about ourselves and others.

Industry in an uproar

What may be good for consumers may not be so great for the photographic industry, which is going through convulsions it hasn't seen since the first burst of innovation when photography was born. It is hard to believe it was only 165 years ago that the daguerreotype -- an image on silver-plated copper -- was introduced to the public.

Daguerreotypes launched the first of several worldwide waves of excitement over the methods inventors developed to record precise images -- on glass, on iron, and finally on paper negatives soaked in silver chloride, the forerunners of the flexible film George Eastman pioneered in 1884.

Modern-day inventors have worked furiously over the past decade to develop electronic sensor systems that have steadily improved the quality of digitally captured images. Late last year, prices tumbled to about $300 for three-megapixel cameras, which meant that, for the same price, people could buy a digital model nearly matching its film counterpart in quality.

Consumers stampeded into digital because it offers two big benefits -- the ability to see photos right away on the camera display screen, and reusable memory cards that make each photo virtually free.

Perhaps nothing illustrates the impact better than Eastman Kodak, the company that popularized film photography and is now fighting for its life -- in January it announced it would lay off about 20 percent of its 64,000 workers and refocus on digital products -- as digital cameras slam sales of film, paper and photo-finishing services. Film sales in the United States have declined every year since their peak in 2000 and are projected to drop 18 percent this year, according to the Photo Marketing Association.

A few years ago, Kodak bought Ofoto, a leading Internet photo-sharing site, to try to capture a share of the retail printing market from digital images -- if and when that market develops. Among the open questions, though, is whether people will print more or less than in the film era, which virtually demanded that all captured images get printed since film was bulk-processed at retail labs. Although people take many more pictures with digital cameras than with film, so far they are printing only 10 to 20 percent of their shots.

"There is less and less need for actual prints due to the pervasiveness of digital displays," said Kristy Holch, group director at InfoTrends/CAP Ventures, which studies the photo industry. "We are just in the early stages where tech-savvy people are displaying photos on their TVs, and we think that will be huge in five years."

While film is in retreat, digital photography is spurring innovation. Camera makers are building image-editing tools directly into their products. Other companies are installing cameras in cell phones , handheld organizers, even key chains. Printer manufacturers are adding photo-display and editing capabilities to the latest generation of photo printers. Among the hot holiday gifts this year are PictBridge home photo printers that connect directly to cameras -- no PC needed -- especially the models that churn out nothing but 4-by-6 prints.

Computer makers, meanwhile, are trying to muscle PCs to the center of the digital universe, making them the place where consumers will store, organize, edit, print and share their growing collections of images.

Microsoft Corp. recently announced it will add software to its Windows XP operating system next year to make plugging cameras into computers much easier. And last week Microsoft announced a new feature for Windows XP designed to speed-order photo prints from retailers online and let consumers pick them up at a local store within a few hours.

"The PC is definitely playing a much larger role in printing, sharing and editing photos," said Josh Weisberg, a Microsoft imaging executive.

But some makers of cameras and printers would prefer an appliance approach, empowering printers and cameras to bypass computers and do more on their own.

"With all due respect to our friends at Microsoft and Apple Computer, digital photography may not need a divorce from the PC, but it may need a trial separation," said Gary Pageau, group executive with the Photo Marketing Association. "Look at the new generation of photo printers that let you edit and print directly from your memory card. They are all PC-less."

Many analysts think digital imaging technology is still too complicated to become as mainstream as film cameras, which found their way into more than 90 percent of American homes because they were point-and-shoot simple. Chris Chute, a senior analyst with research firm IDC, estimates a third of American households own a digital camera now, but he questions how high that number will go.

"There is a digital divide between film use and digital photography use," he said. "It is gentrifying photography, because it really requires a personal computer to take full advantage of digital photography, and a third of U.S. households still don't have a PC."

Changing lives

The human side of the story is still unfolding as people go digital and start exploring.

Bob Feldman, 53, a partner at Silicon Valley's largest law firm, Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, said his high-end Nikon digital camera gave him a second chance at becoming the photographer he always wanted to be.

Feldman said good sports photography requires taking a ton of pictures to learn the correct settings. Digital made it easier by giving him instant feedback on the results of aperture openings and shutter speeds. He has taken thousand of pictures of his son, Nathan, since he became a ball boy for Stanford University basketball four years ago. He also snaps away at other sporting events just for fun.

"I think I am just a year or two ahead of everybody," he said. "In a few years, millions of people will be doing this." Analysts predict booming sales of camera phones will make photography a more casual affair, pushing it out of special moments and into every nook and cranny of people's lives.

"Before, would I have thought of taking a picture of a plumbing part and taking it down to the hardware store to make sure I get the right part? No," said Bryan Lamkin, senior vice president for Adobe Systems. "Can I do that with my cell phone today? Absolutely."

Adobe's Photoshop program has long been the editing tool of choice for professional artists and photographers. Lately the company has been courting digital hobbyists with a less expensive version called Photoshop Elements, basically a virtual darkroom.

"People who previously never even knew a darkroom can get sepia-tone images from color images and achieve all the traditional darkroom processes on the computer desktop," Lamkin said.

Caterina Fake, co-founder of the Web photo-sharing site Flickr, uses her camera phone to send her mother pictures of airport baggage-claim areas each time she lands on trips, to let her know she's arrived safely. Flickr, like other Internet photo services, can display photos sent via e-mail or wirelessly from cell phones and laptops.

A friend of Fake's recently had a baby, and her family documented the event live from the hospital with camera phones, posting the images online so others could watch remotely. "It is a little like having your own personal TV channel or broadcast channel," said Fake.

Internet services such as SmugMug, Webshots, Snapfish and PhotoSite offer a mix of free and premium services. In addition to publicly displaying images, they can archive back-up copies of images and let people create custom photo-gifts, such as calendars, mugs and pet collars.

The archiving issue looms as one of their big selling points.

"Unfortunately, many consumers are heading for disaster with their digital photos," said Holch. "Only half of consumers we surveyed are thinking about long-term archiving and planning some kind of redundancy." Howard Taub, vice president of Hewlett-Packard's image research lab, recommends not only storing images online or on CDs, but on old-fashioned paper. Good prints make the best archive, he said, because they have a shelf life of at least 100 years and can be rescanned later.

Hewlett-Packard is studying ways to add more automation to digital photography. It also is working on software that might one day tell stories about people's photos automatically, using data from such sources as global-positioning-systems.

Microsoft is pursuing similar visions. It showed off a prototype called SenseCam this year, basically a camera in the form of a pendant or other object people can wear. The SenseCam is programmed to sense scene changes and events in people's lives and automatically take a ton of pictures.

A photo chronicle to keep

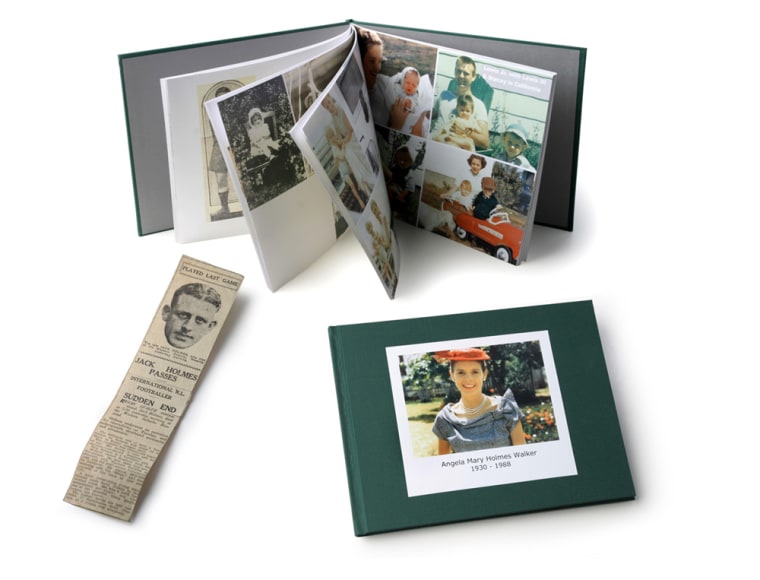

Since my forebears had no SenseCam, I decided to use an Internet publishing service to create a photo book that would chronicle the lives of my mother and her parents. I had had good luck with a service called MyPublisher.com, which offers 9-by-12-inch hardcover photo books starting at $20 for 20 pages.

That's when I pulled out the old velvet folder and, one by one, scanned the newspaper clippings into electronic files and cropped the resulting images into formats to fit MyPublisher's automated layout system. (A scanner works like a copier, only it produces an electronic file inside your computer instead of on paper.) I let the photos tell the story, adding only a few pages of text sketching the lives of my actress mother, Angela Walker, and her fashion-buyer mother, Mary Liversedge, who remarried after her first husband, John Holmes, died.

It was emotionally rewarding to scan and brighten the vintage photos and see details for the first time, like my smiling grandmother waving at a crowd from the train taking her to England's southern coast to board a ship for Australia. Her husband had sailed ahead with the "Kangaroos," as his team was called.

Even more moving were the pictures from a year and a half later, my grandmother clutching her infant daughter and waving from a ship in Australia, this time preparing to sail home.

"Tragic News From Australia," proclaimed the headline on one article published in November 1931. It described the cablegram that had arrived in Yorkshire the previous day. "John died this morning, suddenly. Mary," was all it said. His appendix had burst when he was 26.

Their brief marriage had never seemed real to me, at least not until the photos documenting it were digitized, enhanced, blown up and printed in oversized form on glossy pages inside a coffee-table-quality book. The cover contained an enhanced snapshot of my late mother in her youth, in colors so vivid that my father almost could not bear to open it when I gave it to him for his birthday.

At Thanksgiving, I watched as my sister's 15-year-old daughter, Angela -- named after my mother, who was her grandmother, and who died before Angela was born -- flipped through every page in the book. It gave me great joy to watch her study those old photos of my mother, and read the documents chronicling her brief career as a TV actress in London.

Like me, Angela was getting her first close look at the grandparent she had never known.