Experts advised world museums to re-examine their Bible-era relics after Israel indicted four collectors and dealers on charges of forging items thought to be some of the most important artifacts discovered in recent decades.

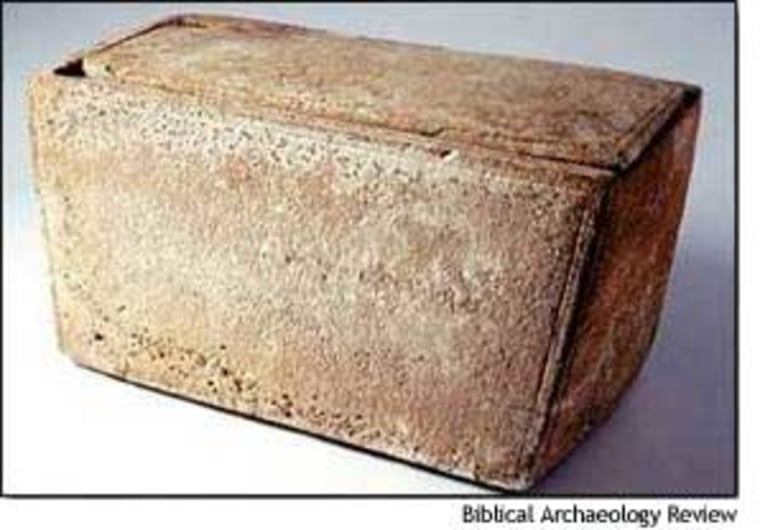

The indictments issued Wednesday labeled many such “finds” as fakes, including two that had been presented as the biggest biblical discoveries in the Holy Land — the purported burial box of Jesus’ brother James and a stone tablet with written instructions by King Yoash on maintenance work at the ancient Jewish Temple.

Shuka Dorfman, head of the Israel Antiquities Authority, said the scope of the fraud appears to go far beyond what has been uncovered so far. The forgery ring has been operating for more than 20 years.

“We discovered only the tip of the iceberg. This spans the globe. It generated millions of dollars,” Dorfman said. The forgers “were trying to change history.”

Exploiting need for evidence

The probe began after the Yoash tablet was offered for sale to the Israel Museum for $4.5 million two years ago. Scholars said the forgers were exploiting the deep emotional need of Jews and Christians to find physical evidence to reinforce their beliefs.

The indictment listed 124 witnesses, including antiquities collectors, archaeologists, officials from Sotheby’s auction house in Israel and representatives of the British Museum and the Brooklyn Museum.

“This does not discredit the profession. It discredits unscrupulous dealers and collectors,” said Eric Myers, an archaeology professor at Duke University in North Carolina.

The forgers would often use authentic but relatively mundane artifacts, such as a plain burial box, decanter or shard, and boost their value enormously by adding inscriptions, Dorfman said. Once the words were engraved, the forgers would try to re-create patina, or ancient grime, to cover the carvings, the indictment said.

Four indicted

The four men indicted were Tel Aviv collector Oded Golan, owner of the James ossuary and the Yoash tablet; Robert Deutsch, an inscriptions expert who teaches at Haifa University; collector Shlomo Cohen; and antiquities dealer Faiz al-Amaleh. The four are free on bail, police said.

A fifth person was indicted, but his name was not released because he is not in the country. Additional indictments were to be issued in coming days, said Shaul Naim, the chief investigator of the Jerusalem police.

Golan said in a statement Wednesday “there is not one grain of truth in the fantastic allegations related to me.” He said the investigation was aimed at “destroying collecting and trade in antiquities in Israel.”

Deutsch dismissed the indictment as “ridiculous.”

Hershel Shanks, editor of the Washington-based Biblical Archaeology Review, said in a telephone interview: “Either this is going to be proven a horrific scandal or the greatest embarrassment to the Israel Antiquities Authority.”

Shanks disclosed the existence of the James ossuary at a November 2002 news conference.

Uzi Dahari, a top official in the Israel Antiquities Authority, said in a recent lecture that some of the forgeries were done by an Egyptian artisan who has worked in Israel for the past 15 years. His habit of bragging about his exploits in a Tel Aviv pub brought him to the attention of police, Dahari said.

Naim said many more fakes are apparently in the possession of collectors and museums worldwide.

Shimon Gibson, an Israeli archaeologist, said museums should review items of questionable origin. “Now it looks like we are going to have to go backward and double-check all our facts to make sure that what we thought was real really is,” he said.

Controversy over pomegranate

Last week, the Israel Museum said one of its most prized possessions, an ivory pomegranate scholars long believed served as the tip of a scepter for Jewish Temple priests, was also a fake.

The indictment listed the pomegranate as one of the items forged by the ring, but no charges were brought in this case because the statute of limitations expired. The pomegranate was bought by the Israel Museum in the late 1980s from an anonymous collector for $550,000.

In a statement, the Israel Museum expressed support for efforts to “end such criminal activities,” adding that its investigation of the authenticity of the pomegranate was its own.

The investigation trained a spotlight on the sometimes murky antiquities trade in the Holy Land.

“It’s a free-for-all market ... and there is no control over something that doesn’t come from a proper excavation, photographed and documented,” Dorfman said.