Saturn’s largest moon apparently is lashed regularly by rain made of liquid methane, forming pools, cutting riverbeds and eroding rocks in much the same way that the force of liquid water has shaped Earth, scientists said Friday.

The European Space Agency’s Huygens probe, which landed on Titan’s frozen surface a week ago, put Europe’s stamp on the distant reaches of the solar system with its discoveries of a mysterious, methane-rich globe.

“We’ve got a flammable world, and it’s quite extraordinary,” said Toby Owen, a scientist from Honolulu’s Institute for Astronomy who was charged with studying the moon’s atmosphere.

Fortunately for Titan, the atmosphere is devoid of oxygen, which would be required to set the methane aflame. “There’s no source of oxygen available, which is a good thing or Titan would have exploded a long time ago,” Owen said.

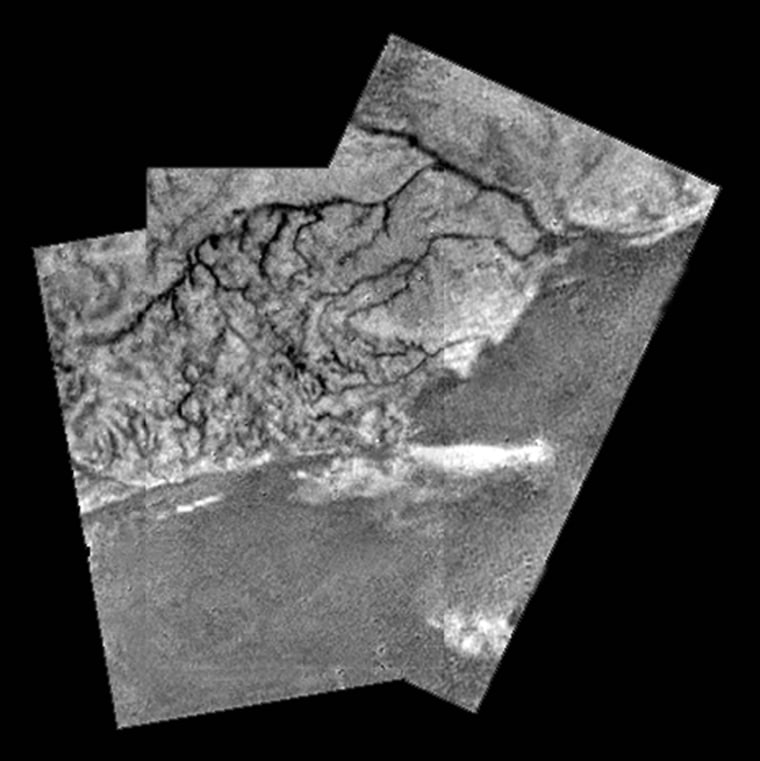

Black-and-white photos from the Huygens probe show a rugged terrain of ridges, peaks, dark vein-like channels and apparently dry lakebeds on the moon 744 million miles (1.2 billion kilometers) away.

Flammable but cold

On Earth, methane is a flammable gas. On Titan, it is a liquid because of the intense pressure and cold — 274 degrees below zero Fahrenheit (-170 degrees Celsius).

“There is liquid that is flowing on the surface of Titan. It is not water — it is much too cold — it’s liquid methane, and this methane really plays the same big role on Titan as water does on Earth,” said mission manager Jean-Pierre Lebreton. “There are truly remarkable processes at work on Titan’s surface and in the atmosphere of Titan which are very, very similar to those occurring on Earth.”

A sensor about the size of a police officer’s nightstick on the front of Huygens probed beneath the moon’s crust and found a material with the consistency of loose sand.

Channels on the surface are evidence of methane rain. There are also what appear to be river systems and deltas, frozen protrusions riddled by channels, apparent dried-out pools where liquid has perhaps drained away, and stones — probably ice pebbles — that seem to have been rounded by erosion.

“Does it rain only once a year? Is there a wet season once a year? Does it rain more frequently? We don’t know,” said another member of the team, Martin Tomasko of the University of Arizona. “The feeling is that in the place we landed, it must rain fairly frequently, but we can’t be more precise than that.”

A cosmic Arizona

The area is “more like Arizona, or someplace like that, where the riverbeds are dry most of the time,” he added. “Right after the rain, you might have open flowing liquids, then there are pools, the pools gradually dry out, the liquid sinks down into the surface. Perhaps it’s very seasonal.”

The river beds are darkened by what seem to be particles of smog that fall out of Titan’s atmosphere, coating the terrain. The dirt apparently gets washed off the ridges by the methane rain to collect in the river channels.

It did not appear to be raining when Huygens descended through Titan’s haze on parachutes, “but it has been raining not long ago,” Lebreton said.

Scientists believe the dark smog particles are formed by Titan’s methane, breaking up in the atmosphere. That raised another question: Where does the methane come from?

“There must be some source of methane inside Titan which is releasing the gas into the atmosphere. It has to be continually renewed, otherwise it would have all disappeared,” Owen said.

But he also cautioned that they should not generalize too much from the area they surveyed about what the rest of Titan might look like.

What next?

Lebreton, the mission manager, said a next possible step in Titan exploration would be to send mobile probes, perhaps balloons to float around before landing.

The Mars rover team has already contacted him to say that “they really now are dreaming of sending their rovers on the surface of Titan,” he added. “This is highly possible — that we can now dream seriously of sending rovers on the surface of Titan. We just need the money.”

The probe was named after Titan’s discoverer, the 17th-century Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens.

Huygens was spun off from the Cassini mother ship on Dec. 24. The $3.3 billion Cassini-Huygens mission to explore Saturn and its moons was launched in 1997 from Cape Canaveral, Fla., a joint effort between NASA, ESA and the Italian space agency.

Titan is the first moon other than the Earth’s to be explored, and David Southwood, ESA’s director of science programs, reflected Europe’s pride in the accomplishment.

“Hello America, we’re in the exploration business, too,” Southwood told reporters.