At times the wind gusted to 35 mph, enough to treat a football like a Nerf ball, enough to sail it, hook it or knock it straight down to the ground. Yet Donovan McNabb kept throwing it Sunday, firing it with heat when necessary, daring to loft it with touch when that was called for. The Philadelphia Eagles fans who booed him on draft day in 1999 never thought he'd amount to much as a quarterback, and certainly didn't think he'd be the one who would deliver them from nearly 25 seasons of football darkness. They wanted Ricky Williams that draft day five years ago. Philly fans wanted a running back, maybe even Edgerrin James, but not some quarterback from Syracuse, not some kid from a school with no history of producing great quarterbacks, and certainly not with the second overall pick in the draft.

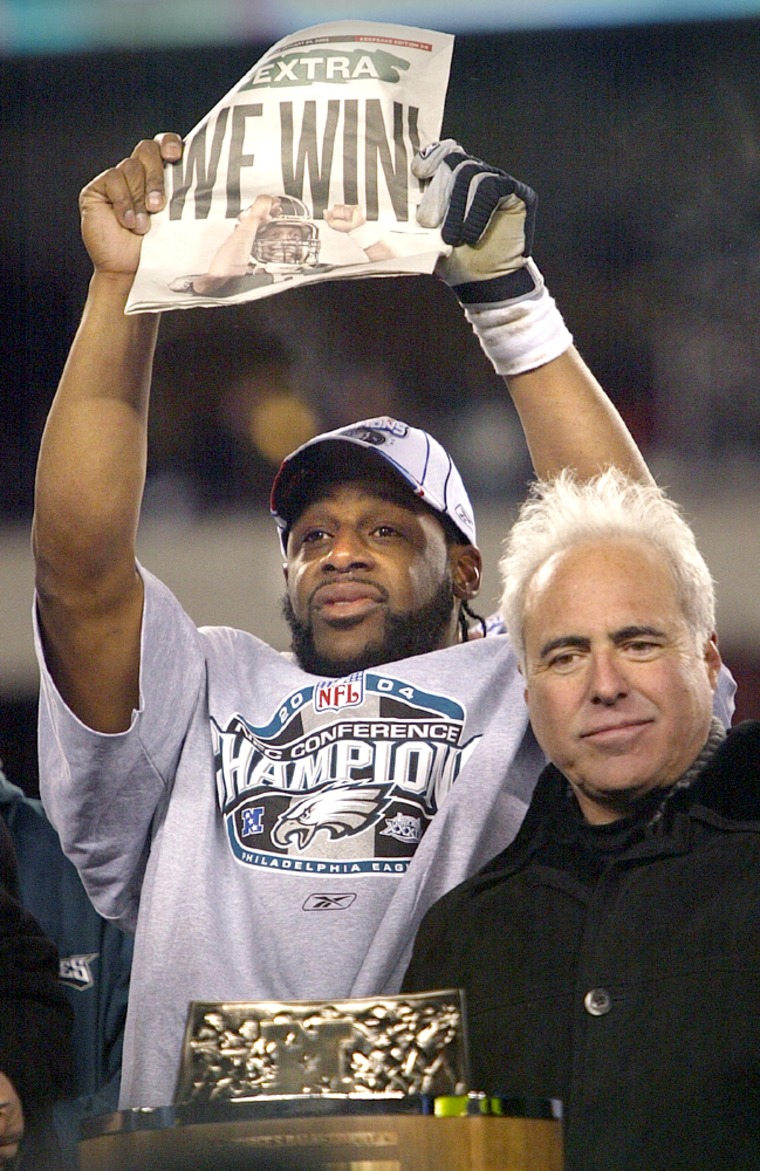

"It was a booing of the Eagles' strategy, of trying to build around a franchise quarterback," owner Jeffrey Lurie said in the locker room after the Eagles had advanced to the Super Bowl with a 27-10 victory over Atlanta. "There are other strategies in the league. But if you get the chance to build around a franchise quarterback, it's best to do just that."

They couldn't envision McNabb completing 17 of 26 passes for 180 yards, two touchdowns and no interceptions in dry calm, much less in sub-zero weather with the wind howling and the pressure of three consecutive championship-game losses threatening to strangle him and the entire city of smothering love. But that's what McNabb did Sunday to the Atlanta Falcons. Without question, Philly's defense flattened the Falcons, held the great Michael Vick to 11 completions in 24 passes and the three-headed rushing entity of Vick, Warrick Dunn and T.J. Duckett to a sparse 99 yards and a 3.8 yards-per-carry average. The Eagles' defensive front was so thoroughly superb in harassing Vick there was no need for defensive wiz Jim Johnson to employ his blitzes, and the Eagles' linebackers and defensive backs were no less than brilliant. Derrick Burgess, Jevon Kearse, Jeremiah Trotter, Brian Dawkins, Lito Sheppard all get a hero's treatment in the retelling of the story.

Still, McNabb was the best player on the field. He found receivers who did not include Terrell Owens. McNabb ran 10 times for 32 yards because he had to, but threw darts to eight receivers because he wanted to. Maybe Vick hadn't seen this kind of wind, but McNabb saw it every other day growing up on the South Side of Chicago. Nobody had a home-field advantage like he did. Nobody had an understanding of how to move the ball like McNabb did, how to use Brian Westbrook's legs not only to advance the ball 96 yards, but to set up run-fake passes to his backs and tight ends.

The Philly fans didn't know what they were getting when they drafted McNabb. They didn't know, as Lurie did, "that from Day One he was solid, that he's from a terrific family, that he's such a hard worker, that over time he would build a spectacular record in this league. He knows the moment and the moments, like great players in every sport, when to make the great pass, when to rebound." Lurie then thought about the talents people try -- and usually fail -- to assess in advance. "He shoulders a lot of pressure," the owner said. "He thrives on it. It's so terrific as an owner of a franchise to have such a classy individual be your team leader, one with humility and tremendous dedication to the sport."

Of course, the Philly fans love McNabb now as much as Red Sox Nation loves Curt Schilling. What boos? The guy who led the booing in New York on draft day 1999 has apologized countless times to McNabb over the years. It's McNabb, even without his batterymate T.O., who took the pain away in the Delaware Valley. It's McNabb who, at least for two weeks until the Super Bowl date with the Patriots, made persecuted Philadelphians forget that they're not the financial capital, 90 miles to the north, or the nation's capital, 135 miles to the south. It was McNabb whose touchdown pass to Chad Lewis made it 27-10 with 3:21 to play and led to such a joyous noise.

They've come to convince themselves over the past 10 years that they are as tortured as Red Sox fans. I called one of my close friends, Duane McKnight, a lifelong Eagles fan transplanted to Washington years ago, because the lead had reached 17 points with only three minutes to play and his fretful reaction was, "It's not over yet." This is the kind of lunacy McNabb has lived with for five years, especially the last three. But it was over. You don't hear a noise that loud very often. Even Eagles Coach Andy Reid said, "They were so loud and obnoxious today when they needed to be. It was great."

This time, their obnoxiousness was directed at anybody but McNabb. "He was booed when he came, but cheered when he left that field today," receiver and teammate Freddie Mitchell said.

I've followed McNabb's football career since his senior year in high school because he comes from where I come, the South Side of Chicago, and because we went to rival high schools. I was thinking, in the immediate aftermath, that McNabb might allow himself one moment to gloat, one moment to say, "Told you so."

But, of course, he wouldn't. He won't celebrate. When congratulated, he said with a smile: "Don't do that. We haven't done what we want to do yet. You know my goal each year is to win the Super Bowl. Don't get me wrong, I'm really excited about this. But we have to play one more game, don't we?

"There's no relief for me. Maybe after the Super Bowl. I set a goal to win the Super Bowl and we're not done."

Nearby stood McNabb's father, Sam. We've come to see a lot of Donovan's mother, Wilma, because of her Chunky Soup commercials. But, yes, Donovan's dad is right there, too. "He knows people have now had to eat their words, but he won't say it," Sam said. "With him, it's not a matter of vindication or, 'I told you.' I taught both my children [older brother, Sean, is 32], 'Let your actions speak.' There's a strong scripture in Proverbs that says if you train a child in the proper direction, when he grows older he will not depart. He's handled some situations better than I would have. I'm proud to see his growth and development as a man. I'm proud he lets his actions represent him. Words don't always communicate effectively. Actions take care of any uncertainty."

A mob of people outside the Eagles' dressing room greeted every player. But the volume rose when McNabb appeared in the corridor. More folks were waiting outside, shivering while hoping to meet him or wave to him. Boos? What boos? The Eagles, for the first time since the 1980 season, were headed to the Super Bowl. The NFC title-game losing streak is over. Ricky Williams? He's out of football, retired or traveling the country searching for Lenny Kravitz or the perfect high. It's McNabb who could be one victory over New England away from hero status in Philadelphia, where he was once shunned. "I think this is what we call closure," Mitchell said with a wink. "I think it's a wrap."