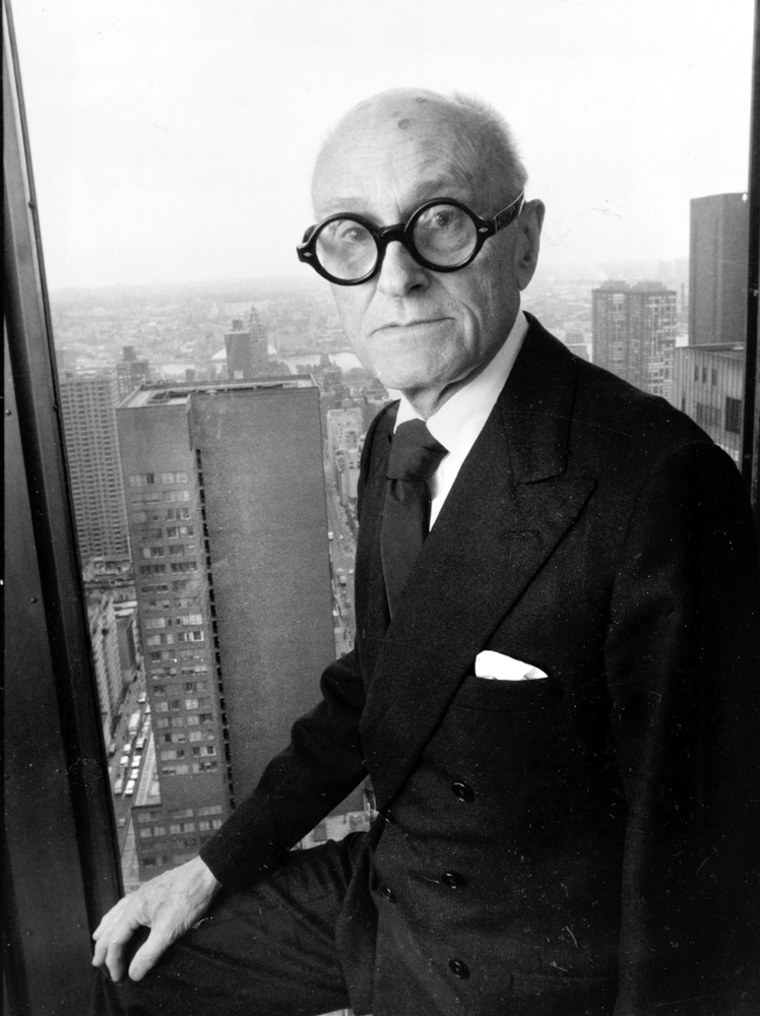

Philip Johnson, the innovative architect who promoted the “glass box” skyscraper and then smashed the mold with daringly nostalgic post-modernist designs, has died. He was 98.

Johnson died Tuesday night at his home in New Canaan, Conn., according to Joel S. Ehrenkranz, his lawyer. John Elderfield, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, also confirmed the death Wednesday.

Johnson’s work ranged from the severe modernism of his New Canaan home, a glass cube in the woods, to the Chippendale-topped AT&T Building in New York City, now owned by Sony.

He and his partner, John Burgee, designed the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, Calif., an ecclesiastical greenhouse that is wider and higher than Notre Dame in Paris; the Bank of America building in Houston, a 56-story tower of pink granite stepped back in a series of Dutch gable roofs; and the Cleveland Playhouse, a complex with the feel of an 11th century town.

“Architecture is basically the design of interiors, the art of organizing interior space,” Johnson said in a 1965 interview.

'The greatest room in the world'

He expressed a loathing for buildings that are “slide-rule boxes for maximum return of rent,” and once said his great ambition was “to build the greatest room in the world — a great theater or cathedral or monument. Nobody’s given me the job.”

In 1980, however, he completed his great room, the Crystal Cathedral. If architects are remembered for their one-room buildings, Johnson said, “This may be it for me.”

He got even more attention with the AT&T Building in New York City, breaking decisively with the glass towers that crowded Manhattan. He created a granite-walled tower with an enormous 90-foot arched entryway and a fanciful top that seemed more appropriate for a piece of furniture.

The building generated controversy, but it marked a sharp turn in architectural taste away from the severity of modernism. Other architects felt emboldened to experiment with styles, and commissions poured into the offices of Johnson-Burgee.

Corporate palaces

Most were corporate palaces: the Transco II and Bank of America towers in Houston; a 23-story neo-Victorian office building in San Francisco, graced with three human figures at the summit; a mock-gothic glass tower for PPG Industries in Pittsburgh.

“The people with money to build today are corporations — they are our popes and Medicis,” Johnson said. “The sense of pride is why they build.”

But his large projects at times ran into a buzz saw of criticism from local preservationists and even fellow architects. In 1987, he was replaced as designer of the second phase of the New England Life Insurance Co. headquarters in Boston after residents complained about the project’s size and style.

Critics unearthed a quotation he had made at a conference a couple of years earlier: that “I am a whore and I am paid very well for high-rise buildings.” Johnson said later his choice of words was unfortunate and he only meant that architects need to be able to compromise with developers if they want to see them built.

Direct and economical

Philip Cortelyou Johnson was born July 8, 1906, in Cleveland, the only son of Homer H. Johnson, a well-to-do attorney, and his wife, Louise. After graduating with honors from Harvard in 1927 with a degree in philosophy, he toured Europe and became interested in new styles of architecture.

That interest became his life’s work in 1932, when Johnson was appointed chairman of the department of architecture of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That same year, he mounted an influential exhibition, “The International Style: Architecture 1922-1932.”

Johnson was especially enthusiastic about the work of the German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who called for designs that express a building’s structure in the most direct and economical way possible. Under such a doctrine, if a building is supported by steel columns, they should be left visible instead of being masked behind stone or brick.

In 1940, Johnson entered the Graduate School of Design at Harvard, studying under Marcel Breuer and testing some theories in a controversial house built in Cambridge, Mass., in 1943. After a stint in the Army Corps of Engineers, he returned to the Museum of Modern Art, designing its west wing in 1951 and the sculpture garden in 1953. He left in 1955 to open his own design office.

Johnson worked with his hero by designing the interiors for Mies’ influential Seagram Building on New York’s Park Avenue, which was completed in 1958.

Reflecting on career and controversy

Johnson’s New Canaan home was built in 1949, a triangular arrangement on a three-level site that won the Silver Medal from the Architectural League of New York in 1950.

Johnson was awarded the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects in 1978, and the following year he became the first recipient of the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize. He was an astute collector of art; what he didn’t have room to display at home, he gave to the Museum of Modern Art.

Toward the end of his life, Johnson went public with some private matters — his homosexuality and his past as a disciple of Hitler-style fascism. On the latter, he said he spent much time in Berlin in the 1930s and became “fascinated with power,” but added he did not consider that an excuse.

“I have no excuse (for) such utter, unbelievable stupidity. ... I don’t know how you expiate guilt,” he says.

He blamed his homosexuality for causing a nervous breakdown while he was a student at Harvard and said that in 1977 he asked the New Yorker magazine to omit references to it in a profile, fearing he might lose the AT&T commission, which he called “the job of my life.”

In the 1950s, Johnson reflected on his career and what he hoped to achieve.

“I like the thought that what we are to do on this earth is embellish it for its greater beauty,” he said, “so that oncoming generations can look back to the shapes we leave here and get the same thrill that I get in looking back at theirs — at the Parthenon, at Chartres Cathedral.”