Challenging a basic tenet of the semiconductor industry, researchers at Hewlett-Packard Co. have demonstrated a technology that could replace the transistor as the fundamental building block of all computers.

The devices, called crossbar latches, could be made so small that thousands of them could fit across the diameter of a human hair, enabling the high-tech industry to continue to build ever-smaller computing devices that are less expensive than their predecessors.

For years, engineers have been able to pack more and more smaller transistors onto a fingernail-size silicon chip. The rate of integration, first predicted by Intel Corp. co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965, has driven computer performance and prices for more than 30 years.

But the pace of Moore's Law can't continue forever, and the high-tech industry has been scrambling to develop workarounds for the day — expected in a decade or so — when transistor dimensions become too small for the materials commonly used today.

"If we're going to extend Moore's Law for another several decades, we've got to have an alternative strategy," said Phil Kuekes, one of the paper's authors at H-P Labs. "This is the final piece of the puzzle in what H-P has been putting together as such a strategy."

The smallest features of today's silicon-based transistors are about 90 nanometers long, a nanometer being roughly one hundred-thousandth the width of a human hair. The crossbar latch, by comparison, can work in a space of about 2 to 3 nanometers.

The H-P research, reported in Tuesday's Journal of Applied Physics, scraps the transistor entirely. In its place is basically a series of platinum wires crossed opposite directions. At the junctions are molecules that in the H-P research happen to be steric acid. "It's metal and molecules. Nothing else," Kuekes said. "We're getting away from the physics of silicon."

Like in a transistor, an electrical signal that passes through a crossbar latch is manipulated to perform logic functions. The latest research shows that the technology also can be used for amplifying a signal, allowing multiple functions to be applied.

"The power of this device is not when it's by itself. It's when it glues together other pieces of logic," said Duncan Stewart, another H-P Labs scientist and study co-author. "As soon as you're able to do that, we call that a computer."

The researchers have not glued together multiple crossbar latches, though they say it's something they're continuing to pursue. They expect it to be commercially viable as early as 2012. The latches are formed through a specialized stamping process for nano-sized imprints.

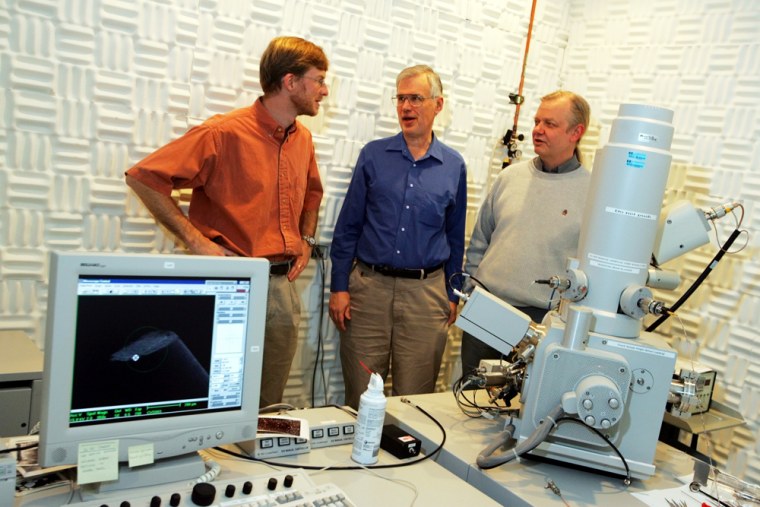

They also must persuade an industry built on transistors that an alternative technology can be just as effective, said Stan Williams, director of Quantum Science Research at H-P Labs and another of the paper's co-authors.

"There came to be a mantra that you have to have transistors to build computers," he said. "A latch is a different way of achieving that same function, but it turns out it has significant advantages over a transistor."

Do more

The crossbar latch not only works at a much smaller scale than a transistor but also can do more, he added. "In order to do the same thing that a latch can do, you actually need many transistors," Williams said.

In fact, other researchers have been focused on building molecular transistors, which are much more challenging to build at such a small scale, said James C. Ellenbogen, principal scientist in the Nanosystems Group at the MITRE Corp.

"This may enable the field to proceed toward nanoprocessor demonstrations and applications more rapidly and at lower cost," he said.

It also could prove to be less expensive to build because engineers can more easily work around defects that arise during manufacturing than with those that occur during silicon fabrication, where defects are avoided at great cost.

But crossbar latches aren't going to replace today's silicon chips anytime soon. At first, they would likely be used for memory and later for specialized devices. They also will have to integrate with today's silicon chips for the time being.

"Transistors will continue to be used for years to come with conventional silicon circuits," Kuekes said, "but this could someday replace transistors in computers, just as transistors replaced vacuum tubes and vacuum tubes replaced electromagnet relays before them."