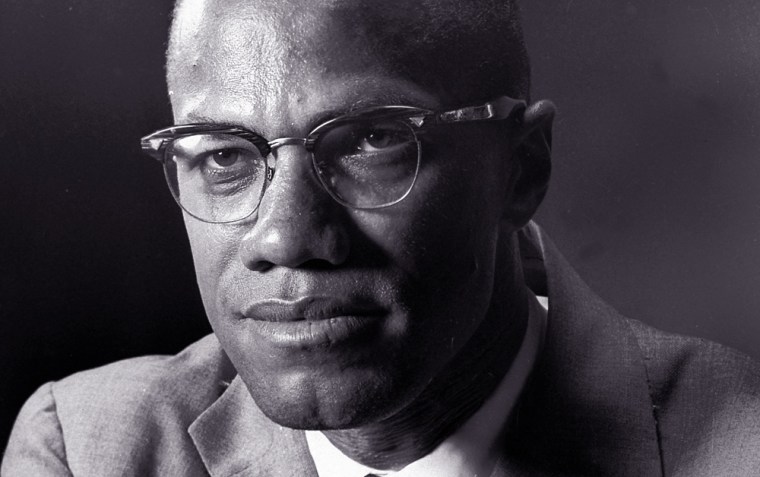

When Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) was shot to death at 3:10 p.m. on Sunday, Feb. 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City, he was perceived as a pariah of the still-burgeoning drive for equality in America — monitored by the police and the government, marginalized by more mainstream civil rights figures, vilified as a danger to the nation.

What a difference two generations makes — and doesn’t make.

Even now, 40 years after his untimely death, many of the issues that dominated the life and career of Malcolm X remain — like the man himself — at the forefront of African-American life, and American life in general.

Today, he inspires black America in particular even as he haunts America in general with a message still seen as hostile, a message that’s spanned five decades and galvanized younger generations more powerfully, in many ways, than more centrist civil rights leaders like the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

From the still-robust sales of his 1965 autobiography to the adoption of his image and oratory by a generation fired by hiphop, the power of Malcolm X has only increased.

The 40th anniversary of his passing comes in an America that has changed, and not changed, in its reception to both the messenger and his message — a nation sometimes angrily sensitized to Islam, Malcolm’s adopted faith.

Power of the word

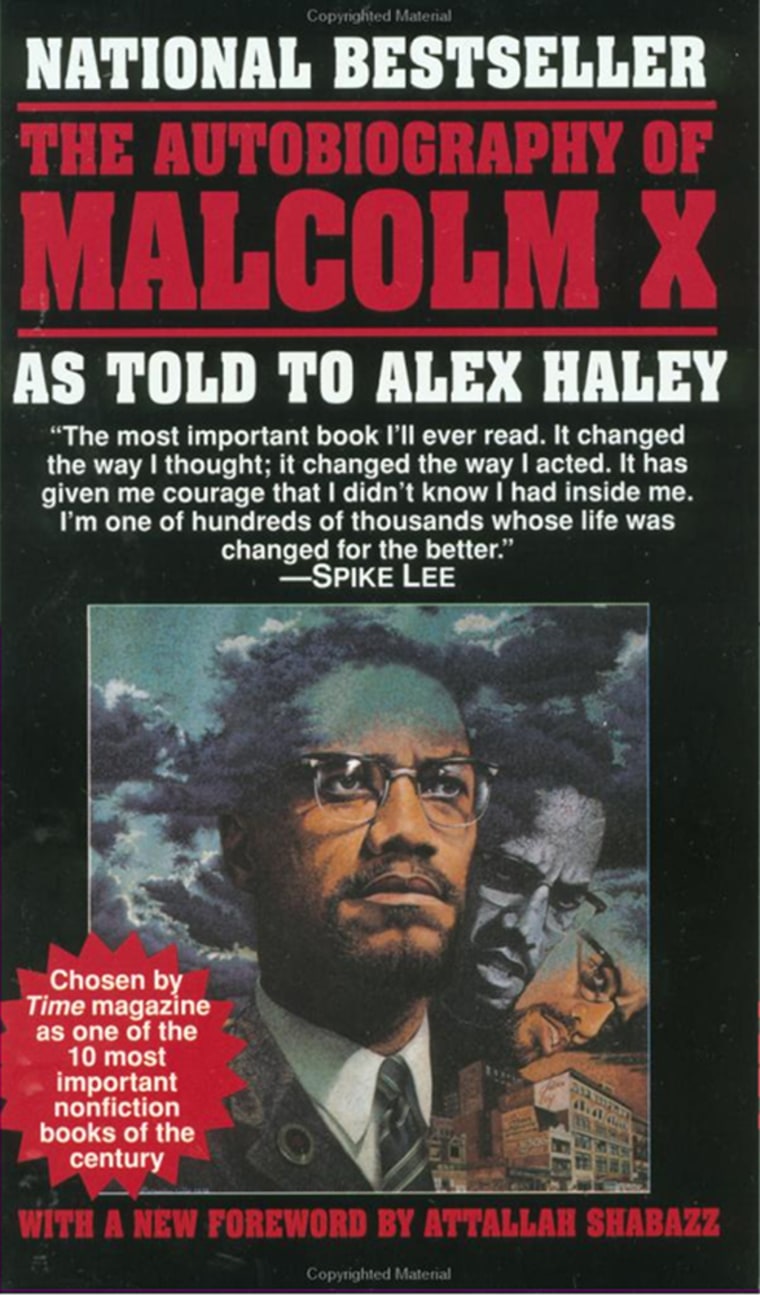

It’s that power of Malcolm X — not just the power of one’s personal transformation, but also the ability to communicate that transformation to a wide audience — that’s evident in his book “The Autobiography of Malcolm X.”

“The Autobiography,” a work whose blazing candor and unflinching self-examination has inspired books from Eldridge Cleaver’s “Soul on Ice” to “Monster,” the autobiography of an L.A. gang member, remains a seminal American work.

By the late 1990s, almost 3 million copies had been sold worldwide, according to the Malcolm X Center at Columbia University.

In 1999, Time magazine selected the book as one of the top 10 nonfiction works of the 20th century.

Embracing a native son, or not

Even as Malcolm X has attained broad recognition in the wider American culture, aspects of his identity are still problematic. The state of Nebraska, where Malcolm Little was born on May 19, 1925, has wrestled in recent years with that recognition.

The Nebraska Hall of Fame, established in 1961 to officially recognize prominent Nebraskans, boasts a range of public figures, including Pulitzer Prize-winning author Willa Cather; anthropologist Loren Eiseley; Gen. John J. (Black Jack) Pershing, commander of American Expeditionary Forces in World War I; and William Frederick Cody, the frontiersman and adventurer more widely known as Buffalo Bill.

How the incendiary presence of Malcolm X would figure in that pantheon of Nebraskans, and whether to embrace him as a native son, has been a matter of debate for the state’s Hall of Fame Commission. Malcolm X was considered but rejected by the commission in April 2004.

A bill currently in the statehouse would seek to have ethnic and gender diversity as factors for consideration. The bill also changes the selection process by requiring public hearings.

“When you consider the makeup of the people on the commision — older white people — the likelihood is not the greatest,” said state Sen. Ernie Chambers of the chances for Malcolm’s inclusion.

“Nebraska is a white-dominated, extremely conservative state,” Chambers said. “Most of the people in the state don’t know anything about Malcolm, and some of those who do have more erroneous information than accurate information.”

Chambers, who is Nebraska’s only African-American state legislator, said the matter is now on an indefinite timetable.

If inducted, Malcolm X would be the first African American to be so enshrined.

Maybe the reactions of the Nebraska lawmakers dogging Sen. Chambers are emblematic of wider American perceptions.

Observances of Malcolm X’s death come in an America still painfully aware of the cultural and philosophical gulf between Christianity and Islam — a gulf no doubt widened by those responsible for the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

“He was aware of the fact that the Islamic population in the world is growing at an incredibly rapid rate, in the United States it’s growing significantly,” said Howard Dodson, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, based in New York City.

“That means that Americans will have to come to terms with Islam within the United States and outside, and formulate positions at individual and societal levels that bring the same respect to Islam that people bring to Christianity,” Dodson said. “That kind of respect will be won over time. It won’t happen overnight.”

For Dodson, Malcolm’s place in history is secure. “Malcolm’s right up there with Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela in the pantheon of leaders of 20th century black history,” he said.

“He resonates and continues to be a voice and presence 40 years later, in large measure because of the kind of life he lived,” Dodson said. “He was as hard on black America as he was on American society.”

“He reached a point in his life where he could not not speak the truth, and in a society where we’re still in the process of desegregation,” Dodson said.

“Black men who had the courage — the audacity, quite frankly — to speak their minds were perceived as a threat,” he said. “It’s interesting that he was seen as a purveyor of violence. There’s no instance that I’m aware of in his public life in which he initiated violence against anyone. But he was a proponent of the defensive position — strike back if stricken.”

Not so far apart

Dodson dismissed another old assumption: that Malcolm X and King, the civil rights leader perceived as more palatable both in message and method, were light years apart in their thinking.

“The tendency to create polar opposites, which is what media did at that time, doesn’t reflect the struggle,” Dodson said.

“Malcolm had shifted into a broader humanistic perspective, upgrading the position of black, Hispanic and native Americans,” he said. “But they were part and parcel of the same program. Malcolm said in so many words, ‘either you deal with Martin King or you deal with me.’"

For Ilyasah Shabazz, one of six daughters in the Shabazz household, relationships between the two leaders were both a matter of history and a family affair.

“In American history we have Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. Both men are embraced and respected for what they contributed as fathers of their country. Malcolm and Martin also both contributed, tremendously,” she said.

“It’s too bad that African-Americans often pit one against another. Both gave their lives for our cause and both contributed, however differently or similarly, and both gave their lives for what they believed in. Our families have always been close. We share the same pain and outlook on life and joys.”

Growing up Ilyasah

Like her illustrious father, Shabazz took pen in hand to make sense of her past. “Growing Up X” (One World/Ballantine), her 2002 self-described “coming of age memoir,” is at once a tribute to her mother, Dr. Betty Shabazz; an attempt to come to grips with the loss of a father in highly unnatural terms; and an expression of a life in the shadow of one of the 20th century’s most powerful voices.

Ilyasah Shabazz finds that the country has shifted some in its reception of messenger and message.

“America has certainly changed in its embrace of brotherhood, in being able to look at humanity and accepting the contributions of all of us. I don’t know how much it’s changed."

Shabazz, who lives in Mount Vernon, N.Y., credits her mother for the spark to write.

The book, she said, “really serves as a tribute to my mother ... just examining her life — while she was in her twenties, her husband was assassinated in front of her, her home was firebombed, [she was] a woman with four babies and pregnant with twins — she accomplished so much while serving humanity.”

Props for her pops

Shabazz, who was only 2 when Malcolm was slain, bears love for her father that’s equally heartfelt. “He was just a young man; that’s what surprises people,” she said. “He was only in his twenties when he burst on the scene.

“This was a regular young man in search of his identity as a man and as a person of African descent and reconnecting us to what we had before bondage … that psychological trauma we see the results of today,” she said.

“He didn’t cower, didn’t compromise his values or integrity. Like Ossie Davis said in the eulogy, Malcolm was our manhood — he was his nation’s manhood. He was unwavering. After a speech I gave once, a young white male student came up and told me, ‘There are only two men I respect in my life — your father and mine.’ ”

“In a sense, Malcolm drove people to King,” said Chambers, the Nebraska state senator. “They would rather contend with someone like Martin Luther King, who said ‘suffer in silence,’ than to deal with Malcolm who said ‘if you hit me, I’m going to hit you back.’ ”

That sense of defiance, a streetwise forthrightness about personal integrity and the need for self-defense, has endeared Malcolm X to the hip-hop generation.

“Hip-hop is not just a style of music, it’s a way of life, a philosophy, and the philosophy of hip-hop comes, in a large part, from the philosophy of Malcolm X,” said Sandeep Atwal, publisher of the political/cultural blog Infernal Press, to the Web site AllHipHop.com.

Full circle at 40

There’s a sense of things having come full circle — or nearly so — for the Audubon Ballroom, the site of the tragedy. On Monday, 40 years to the day of the assassination, the location on upper Broadway in Washington Heights will be where the Shabazz family celebrates Malcolm’s life, at what is now called the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Education Center.

The 2005 observances follow efforts to preserve the site announced in October 1997: New York City, through its Economic Development Corporation, had to that time invested more than $19 million in renovating the building, according to the mayor’s press office. Since then, however, efforts to use the location have faced complications but seem to be getting back on track.

The ballroom’s new center will house a multimedia environment containing documents about Malcolm X’s life, including memoirs, notes, speeches and other personal items.

“It preserves an important historic landmark,” Ilyasah Shabazz said of the site. “It’s about not living a life of bitterness and despair, but finding the good and praising it. Each individual has their share of life’s tragedies. You can’t live life as a victim. We would rather smile and stand than to cry and be bitter and broken. This is all a part of life’s journey.”