From roadside jerk stands to bohemian hideaways to white-glove resorts, this Caribbean hot spot has something for everyone. Matt Lee and Ted Lee embark on a road trip to get a taste of what the island has to offer.

Whether they know it or not, most people travel with a muse in mind. For many, it's Jackie O., being whisked in and out of glamorous European settings followed by her matching valises; for others, it might be Percy Bysshe Shelley, lugging a rucksack and a diary to the far side of the Mediterranean to commune with the ancients. For us, it's Bond, James Bond, the British secret agent who set an example no teenage boy could resist, slipping through kitchen doors, wallowing in ditches by day, and miraculously coming up clean to tango with Octopussy at cocktail hour.

James Bond was born on Jamaica, in tiny Oracabessa in the parish of St. Mary. It was here that Ian Fleming brought 007 to life, in 1952, writing Casino Royale, the first in the series, by lamplight in a ranch overlooking the sea. Even though Bond is a fiction, it makes sense that there's some Caribbean DNA in the guy—it's discernible in his barefoot bravado, and also in his inevitable return to a lounge chair under the palms, drink in hand (you know the one), a babe massaging his shoulders as the credits roll.

And yet it's hard to imagine Bond cooped up within the gates of one of Jamaica's all-inclusive resorts (another lucrative concept that was born here). So on a recent trip to the island, we decided to honor our muse by taking a more adventurous route, one that might expose us to the full scope of Jamaican landscapes and opportunities. We would land in metropolitan Kingston, the capital, pick up a basic 4 x 4 (an Aston Martin wasn't readily available), climb 7,500 feet into the Blue Mountains, and then descend to the island's north side. We'd trace the coastal road west, checking into a few select resorts, including Goldeneye, Bond's birthplace. We'd drop in on the commercial bustle of Negril, at Jamaica's westernmost outcropping, before heading to the unhurried agricultural parish of St. Elizabeth and the remote southern coast.

Slideshow 20 photos

Caribbean way of life

Or so we thought. As we soon discovered, a ground-hugging Aston Martin wouldn't have made it around the first bend on Jamaica. It was pouring in Kingston on day one, and even our nimble Suzuki struggled with the pizza box-sized potholes, the washouts, and the rockslides of the mostly two-lane A1, the island's north-south thoroughfare. Since there were no route markers, the only sure sign that we were on the right road was the steady stream of gasoline trucks careening around hairpin turns ahead, scattering goats and pedestrians. We hastily abandoned our plans to visit the Blue Mountain coffee plantations at the higher elevations, as it was clear by mile two that we'd never reach our eventual destination by daybreak—if we made it at all.

So we set a slightly less adventurous course and drove straight to Goldeneye, the resort that Chris Blackwell, founder of Island Records, built from the old Ian Fleming estate, at the far eastern end of the string of north-coast properties that extends from Montego Bay airport. Inside Goldeneye's wrought-iron gates we were greeted by a lush tropical forest of tall African tulips, mango and lime trees, and rare cannonball trees with ropy limbs that hung to the ground. In 1995, Ann Hodges, perhaps Jamaica's most renowned living architect, designed the shingled cottages tucked beneath the vegetation and connected by stone-and-pebble paths. Goldeneye accommodates only 26 people, in six villas decorated with bamboo and batiks in a clean, tropical style we call tiki luxe. Each lodging, with its carefully screened outdoor shower, is far enough from the others to offer total seclusion to the likes of Naomi Campbell and Jim Carrey.

We kicked off our shoes and headed for the cliffside gazebo that serves as the resort's communal dining area and bar. Settled in with our drinks, we looked down from its white-painted deck at the lagoon that surrounds the property, watching as other guests (an even mix of couples and families) shuttled in with their towels and flippers from the private beach, accessible by a tiny ferry. Beyond the beach—the launching point for our Jet-Ski expedition the next morning—we could see the Caribbean. We raised the house cocktail, a blend of dark rums sweetened with pineapple juice and lime, and toasted our safe delivery from the A1. A helicopter fluttered into range, then landed briefly—more guests were arriving.

Goldeneye's kitchen, under Pamela Clarke, endeavors to use local produce from farmers in St. Elizabeth Parish and turns out hearty, if square, island fare. Grilled beef tenderloin and curried shrimp were the features that night, accompanied by a savory shredded coconut-cabbage slaw. As darkness descended, the gazebo glowed like a lantern, and by dessert the skunky perfume of marijuana from the honeymooners' table drifted across to ours.

As we traveled farther west along the coast, under a Caribbean sun at full strength, we were able to steep ourselves in the texture of the Jamaican roadside. We experienced more of the bone-shaking conditions and close calls with cows and chickens on the loose, but we were pleased to find some grace notes as well—examples of the architecture Hodges may have been riffing on at Goldeneye. Tiny towns such as Duncans and Falmouth boasted more than a few pretty pastel houses, verandas with railings of gingerbread fretwork, and cream-colored stone buildings from the 19th century, including a handsome church and parish hall. Corrugated shacks and huts were by far the norm in the countryside, but most intriguing to us were hundreds of hollow cement palaces, frozen in mid-construction, casting a ghostly presence over the island. "Cash flow," a hotelier would later explain.

The closer we got to Montego Bay, the tourist heart of Jamaica, the more we saw the true symbol of cash flow—the security gate. At the entrance to each resort was an imposing metal barricade and a manned guardhouse, reminders that at one time every traveler to Jamaica needed to be as intrepid (if not as well armed) as 007. In the late sixties, the rise to power of a militant Socialist regime forced investors to flee the island, and as the economy declined, much of Jamaica's workforce followed. Race relations deteriorated such that by the early seventies, Uzi-toting sentries guarded any resorts that hadn't been abandoned. These days, the function of gates seems more one of intimidation than security. Like the hazardous roads, they end up benefiting resorts by encouraging guests to keep themselves—and their wallets—inside the compound.

Which only made us more determined to find a local lunch. In Rio Nuevo a man with dreadlocks to his waist and wearing only shorts was selling an octopus by the roadside—holding it aloft with one hand, like a Jamaican Perseus. But alas, our 4 x 4 had no kitchen. The scent of burning pimento wood, the preferred fuel for jerk preparation, began to call out to us from corrugated sheds with names like Try Me, Dis and Dat, and Pon de Corner Jerk Stop.

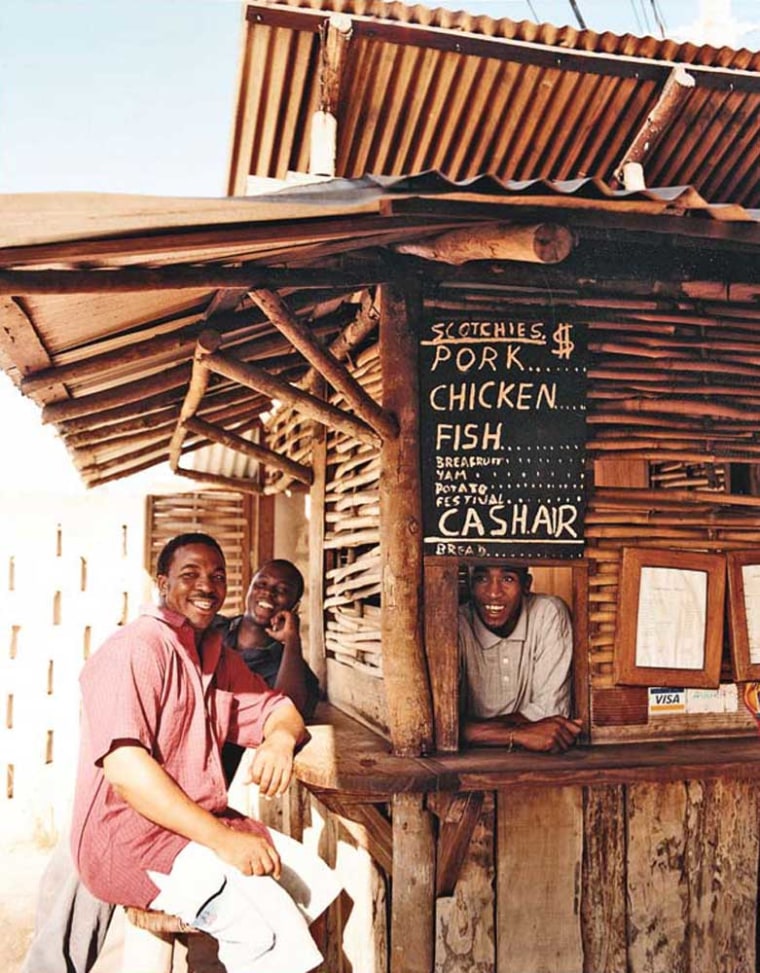

A mile from the Montego Bay airport (and about 10 miles from the gates of the Ritz-Carlton, Mo'bay's most luxurious resort, featuring its own jerk pit and live reggae venue), a steadily rising plume of smoke drew us to Scotchies, a thatched encampment in a sandy parking lot. After placing our order at the window, we sidestepped to a counter that overlooked smoldering fires where chickens and pork shoulders were slowly blackening. We watched as a cook in blue coveralls hacked the chicken into parts and transferred it to a takeout container. We ladled on extra marinade, studded orange and green with chopped Scotch bonnet peppers (whose earthy undertone is the defining feature of jerk). The fish, cooked on a smaller barbecue rig in the parking lot, was less assertively spicy, steamed in foil with sliced tomato and okra, onions, and black pepper. Grass umbrellas shaded the outdoor dining area, where beer kegs served as stools.

The luxury quotient was far higher on the other side of Montego Bay, at Round Hill Hotel & Villas, one of the island's older resorts, opened in 1953. The jalousied villas in the compound are set into a steep, amphitheater-like hillside, offering a perfectly composed view of the azure sea: scalloped coves rippling into the distance on the left, framed by floppy banana leaves and latticed arches, tied-back curtains and clouds. One's toes—and perhaps a sail or two on the water—are the only intrusions on the scene.

Our own adjoining suites, done entirely in white (the original black-and-white floor tiles peeked out beneath the new), shared a large pool, as well as a full kitchen that hummed with activity early the next morning. A breakfast table was set for us on the porch, and it was here that we were introduced to ackee, a tropical fruit (Blighia sapida) native to Africa. Ackee is firm but soft—tofu-like—and is sautéed with salt cod, onions, and tomatoes to produce the Jamaican national dish, "ackee and codfish," a salty, nutty, fishy, and delicious stir-fry that resembles scrambled eggs. Like bagels and lox, it's perfect brunch food.

Christie, the pool tender, noticed our interest in the citrus trees that grew around the pool and offered to take us on a botanical tour of the property. The predominant specimens included green oranges and yellow limes, bougainvillea, avocado, ginger lily, hibiscus, and our newfound friend ackee—whose fruit is an almost fluorescent scarlet red and must be carefully harvested and prepared to be edible.

Although it was tempting to remain in our roost and request one of the resort's chefs to cook for us, we emerged later that day to check out the dinner scene at the beachside cabana. The remodeled bar delivered on the kind of Newport-style elegance we had heard about, with white-jacketed waiters, a bar resembling the deck of a vintage Chris-Craft, boldly striped upholstery, and framed photos of Round Hill family and visitors, including Paul McCartney, Demi Moore, and Bob Hope.

We'd arrived early for dinner, so we lingered at the bar, nursing rum punches. Suddenly, a piercing voice shattered the quiet cocktail din.

"Excuse me!" a woman shouted across the room at a waiter taking a couple's drink order. She wore a sheer beach sarong with a matching bikini and head scarf. "Those chicken skewers we had Tuesday?"

The waiter looked up from his pad.

"Get me some," she said. "Now."

It was the first time that we wished the front gate had been more effective.

Things had lightened up considerably by dinnertime, which at Round Hill invites something swankier than flip-flops: a few women had put their hair up, a couple of men had willingly donned jackets. We managed to insinuate ourselves into a group of "moms gone wild" (their words), three young ladies from the New York area who had left husbands and children behind for a weekend of reading and massages in the Caribbean. As we all dug into escabeche—snapper with pickled onions and peppers—and lobster, a reggae quartet of senior citizens serenaded the table. Be sure to have the name of your favorite reggae classic at the tip of your tongue; if you don't, the default is "No Woman, No Cry."

The drive into Negril the following morning represented a comedown from the beauty of Round Hill; the lavender bunkers of the Rui resort were followed closely by a nightclub compound called the Jungle and a concession that rents chopper motorcycles by the hour. But our own hotel, on the far side of town, was something else entirely, a hip resort for design mavens, as imagined by Fred and Wilma. The walkways and the octagonal, thatched-roof huts at the Rockhouse Hotel are constructed of a bright sand-colored stone with the texture of coral. The villas sprawl along craggy, wave-swept cliffs; next to the chaise lounge on the terrace of our lodging was a narrow staircase that led into the Caribbean 20 feet below, where we could enjoy a refreshing mid-afternoon snorkel among the coral reefs.

Negril is a town with a partying spirit, and at the Rockhouse—which has a guard gate but no guard we ever saw—the social center is the hotel's restaurant, an indoor-outdoor terrace cantilevered over the water. The menu brings local food up to date in smart, refreshing ways: a crisp, oniony conch fritter came with a papaya-and-lime salsa that was bracingly sweet and tart. Fried red snapper was beer-battered with Red Stripe, and—finally!—on each table was a bottle of the condiment Pickapeppa, an aged purée of tamarinds and Scotch bonnets that to our minds is Jamaica's best, and most overlooked, export.

Ten minutes into our meal, the proprietor of a shop across the street dropped by the tables, introduced himself as Beezy, and offered us island exports of a more rarefied sort.

"I got good ganja, good blow, good jerk chicken," he said. "One-stop shopping, mon."

We took a rain check and made a beeline for the infinity pool. If overtures from local merchants are the trade-off for not feeling penned-in, we figured we could handle it.

Soaking up to our chins, we listened in as the staff hustled around in white polo shirts, delivering fruity drinks to a party of creative types from an ad agency who were nattering on about "the Volvo shoot." Where Goldeneye seems to court an aging jet set of rock-and-rollers and supermodels, and Round Hill an old-money, spa-and-golf crowd, Rockhouse's free Wi-Fi and pulsing sound track caters to young swells who network as hard as they play. Take away the thatched roofs and the coral, and we might have been on the roof deck of the Meatpacking District's Soho House.

And that's the vibe of Jamaica now. Like resorts in the Caribbean at large, properties here have the will, not to mention the prosperity, to specialize. Each has refined its amenities to home in on a distinct contemporary lifestyle; one resort, fresh from a renovation and eager to show its new-money bona fides, boasts of having Italian Mascioni linens as well as Jamaica's first caviar bar (with a Veuve Clicquot partnership, of course).

With the hustle of Negril behind us, we drove south along the coast road, into more pastoral land, a hill country of sugarcane and scallion fields. As the scenery became more rural, the roads counterintuitively widened. Near Treasure Beach we took a detour north, to Middle Quarters, to find the fiery "pepper shrimp" the town is famous for.

At the end of a mile-long avenue of bamboo was Howie's, a long, low shed with a dozen steaming, smoke-blackened steel cauldrons set in a row, each balanced on its own tripod of rocks over a few burning logs. Several cooks tended pots of conch, fish, and oxtail. When we asked for pepper shrimp, a gaunt man named Peckes consulted a woman named Vila, who picked up a cordless phone and placed an unintelligible call.

"Soon come," she said. "Soon come." We ordered bowls of a sweet, almond- and-bay-leaf-scented peanut porridge, but 15 minutes later, there was no sign of shrimp. Vila made another phone call.

"Soon come," she repeated. "Soon come." Ten minutes passed. As we were on the brink of leaving, a tall woman emerged from a house on the hill.

She introduced herself as Margaret Stone and set down a large stainless-steel bowl heaping with flaming red "shrimp"—large river crayfish that looked like tiny lobsters. Stone shoveled a pound into a black plastic sack, along with "extra spoonfuls for waiting."

The shrimp had been stir-fried with minced Scotch bonnet peppers, coarse sea salt, pepper, and vinegar. They were spicy, sweet, and addictive, and they may just be the most delicious—certainly the messiest—car snack ever.

The south coast was the part of Jamaica hardest hit by Hurricane Ivan last September, and on our way to Treasure Beach, we saw gaping fissures where the rushing water had dug into cracks in the roads. The cattle ranches and open fields seemed to bustle with activity despite the area's sleepy reputation. Then again, we'd also heard that Jake's, our next resort, was a quirky place. The vintage car sitting on four flat tires at the entrance seemed more ominous than inviting.

We needn't have worried. A welcoming party—a gang of lazy Jack Russells—had assembled around the front desk, and at the bar, Dougie Turner, who's been pouring drinks at Jake's for 12 years, was mixing perfect margaritas using yellow limes. An angler who lives two coves down was ready to whisk us out for some fishing in his boat, One Love. That night at dinner, a neighborhood wood-carver dropped by our table and showed us two beautiful busts he'd carved from polished pimento wood. A self-proclaimed wise man, he seemed more interested in trading proverbs than closing a sale.

Our villa was a tiny one-room shanty perched on stilts over the shore break, with window and door frames made of driftwood, brightly colored glass bottles embedded in the stucco walls, and a padlock and chain holding the door fast, if you cared to close it at all.

There are only 15 villas at Jake's, the most luxurious of them miniature Moroccan-inspired riads with rooftop decks and canopied harem beds, but none have televisions or telephones. And while the resort's bohemian whimsy seems to attract a young crowd, it's the kind that happily leaves the BlackBerry and the laptop behind. By comparison with the Rockhouse, the scene here was serene: a small pool fed by ocean water, a scattering of Adirondack chairs.

There's an organic quality to the place, which makes sense. Sally Henzell, the hotel's co-owner, was born and bred in Treasure Beach and raised her son, Jason, and daughter, Justine, there. The siblings are taking Jake's into the 21st century, but instead of banking its future on first-world luxuries, they're updating it with the annual Calabash Literary Festival and guided tours of Treasure Beach's roadside pubs.

Of all the hotels we stayed at on Jamaica, Jake's was unique in seeming to grow out of the place rather than imposing itself upon it—a fact that made for its own kind of intrigue. On our last night, when we returned from dinner, as our key turned in the padlock we heard a rustling in the bushes. Like 007, we flattened ourselves against the shadows of the eaves, breathlessly waiting for the intruder to make a move. And then, over a stone parapet, came one claw, then another, of a very large crab, making its way back to the sea.

From roadside jerk stands to bohemian hideaways to white-glove resorts, this Caribbean hot spot has something for everyone. Matt Lee and Ted Lee embark on a road trip to get a taste of what the island has to offer.

Whether they know it or not, most people travel with a muse in mind. For many, it's Jackie O., being whisked in and out of glamorous European settings followed by her matching valises; for others, it might be Percy Bysshe Shelley, lugging a rucksack and a diary to the far side of the Mediterranean to commune with the ancients. For us, it's Bond, James Bond, the British secret agent who set an example no teenage boy could resist, slipping through kitchen doors, wallowing in ditches by day, and miraculously coming up clean to tango with Octopussy at cocktail hour.

James Bond was born on Jamaica, in tiny Oracabessa in the parish of St. Mary. It was here that Ian Fleming brought 007 to life, in 1952, writing Casino Royale, the first in the series, by lamplight in a ranch overlooking the sea. Even though Bond is a fiction, it makes sense that there's some Caribbean DNA in the guy—it's discernible in his barefoot bravado, and also in his inevitable return to a lounge chair under the palms, drink in hand (you know the one), a babe massaging his shoulders as the credits roll.

And yet it's hard to imagine Bond cooped up within the gates of one of Jamaica's all-inclusive resorts (another lucrative concept that was born here). So on a recent trip to the island, we decided to honor our muse by taking a more adventurous route, one that might expose us to the full scope of Jamaican landscapes and opportunities. We would land in metropolitan Kingston, the capital, pick up a basic 4 x 4 (an Aston Martin wasn't readily available), climb 7,500 feet into the Blue Mountains, and then descend to the island's north side. We'd trace the coastal road west, checking into a few select resorts, including Goldeneye, Bond's birthplace. We'd drop in on the commercial bustle of Negril, at Jamaica's westernmost outcropping, before heading to the unhurried agricultural parish of St. Elizabeth and the remote southern coast.

Or so we thought. As we soon discovered, a ground-hugging Aston Martin wouldn't have made it around the first bend on Jamaica. It was pouring in Kingston on day one, and even our nimble Suzuki struggled with the pizza box-sized potholes, the washouts, and the rockslides of the mostly two-lane A1, the island's north-south thoroughfare. Since there were no route markers, the only sure sign that we were on the right road was the steady stream of gasoline trucks careening around hairpin turns ahead, scattering goats and pedestrians. We hastily abandoned our plans to visit the Blue Mountain coffee plantations at the higher elevations, as it was clear by mile two that we'd never reach our eventual destination by daybreak—if we made it at all.

So we set a slightly less adventurous course and drove straight to Goldeneye, the resort that Chris Blackwell, founder of Island Records, built from the old Ian Fleming estate, at the far eastern end of the string of north-coast properties that extends from Montego Bay airport. Inside Goldeneye's wrought-iron gates we were greeted by a lush tropical forest of tall African tulips, mango and lime trees, and rare cannonball trees with ropy limbs that hung to the ground. In 1995, Ann Hodges, perhaps Jamaica's most renowned living architect, designed the shingled cottages tucked beneath the vegetation and connected by stone-and-pebble paths. Goldeneye accommodates only 26 people, in six villas decorated with bamboo and batiks in a clean, tropical style we call tiki luxe. Each lodging, with its carefully screened outdoor shower, is far enough from the others to offer total seclusion to the likes of Naomi Campbell and Jim Carrey.

We kicked off our shoes and headed for the cliffside gazebo that serves as the resort's communal dining area and bar. Settled in with our drinks, we looked down from its white-painted deck at the lagoon that surrounds the property, watching as other guests (an even mix of couples and families) shuttled in with their towels and flippers from the private beach, accessible by a tiny ferry. Beyond the beach—the launching point for our Jet-Ski expedition the next morning—we could see the Caribbean. We raised the house cocktail, a blend of dark rums sweetened with pineapple juice and lime, and toasted our safe delivery from the A1. A helicopter fluttered into range, then landed briefly—more guests were arriving.

Goldeneye's kitchen, under Pamela Clarke, endeavors to use local produce from farmers in St. Elizabeth Parish and turns out hearty, if square, island fare. Grilled beef tenderloin and curried shrimp were the features that night, accompanied by a savory shredded coconut-cabbage slaw. As darkness descended, the gazebo glowed like a lantern, and by dessert the skunky perfume of marijuana from the honeymooners' table drifted across to ours.

As we traveled farther west along the coast, under a Caribbean sun at full strength, we were able to steep ourselves in the texture of the Jamaican roadside. We experienced more of the bone-shaking conditions and close calls with cows and chickens on the loose, but we were pleased to find some grace notes as well—examples of the architecture Hodges may have been riffing on at Goldeneye. Tiny towns such as Duncans and Falmouth boasted more than a few pretty pastel houses, verandas with railings of gingerbread fretwork, and cream-colored stone buildings from the 19th century, including a handsome church and parish hall. Corrugated shacks and huts were by far the norm in the countryside, but most intriguing to us were hundreds of hollow cement palaces, frozen in mid-construction, casting a ghostly presence over the island. "Cash flow," a hotelier would later explain.

The closer we got to Montego Bay, the tourist heart of Jamaica, the more we saw the true symbol of cash flow—the security gate. At the entrance to each resort was an imposing metal barricade and a manned guardhouse, reminders that at one time every traveler to Jamaica needed to be as intrepid (if not as well armed) as 007. In the late sixties, the rise to power of a militant Socialist regime forced investors to flee the island, and as the economy declined, much of Jamaica's workforce followed. Race relations deteriorated such that by the early seventies, Uzi-toting sentries guarded any resorts that hadn't been abandoned. These days, the function of gates seems more one of intimidation than security. Like the hazardous roads, they end up benefiting resorts by encouraging guests to keep themselves—and their wallets—inside the compound.

Which only made us more determined to find a local lunch. In Rio Nuevo a man with dreadlocks to his waist and wearing only shorts was selling an octopus by the roadside—holding it aloft with one hand, like a Jamaican Perseus. But alas, our 4 x 4 had no kitchen. The scent of burning pimento wood, the preferred fuel for jerk preparation, began to call out to us from corrugated sheds with names like Try Me, Dis and Dat, and Pon de Corner Jerk Stop.

A mile from the Montego Bay airport (and about 10 miles from the gates of the Ritz-Carlton, Mo'bay's most luxurious resort, featuring its own jerk pit and live reggae venue), a steadily rising plume of smoke drew us to Scotchies, a thatched encampment in a sandy parking lot. After placing our order at the window, we sidestepped to a counter that overlooked smoldering fires where chickens and pork shoulders were slowly blackening. We watched as a cook in blue coveralls hacked the chicken into parts and transferred it to a takeout container. We ladled on extra marinade, studded orange and green with chopped Scotch bonnet peppers (whose earthy undertone is the defining feature of jerk). The fish, cooked on a smaller barbecue rig in the parking lot, was less assertively spicy, steamed in foil with sliced tomato and okra, onions, and black pepper. Grass umbrellas shaded the outdoor dining area, where beer kegs served as stools.

The luxury quotient was far higher on the other side of Montego Bay, at Round Hill Hotel & Villas, one of the island's older resorts, opened in 1953. The jalousied villas in the compound are set into a steep, amphitheater-like hillside, offering a perfectly composed view of the azure sea: scalloped coves rippling into the distance on the left, framed by floppy banana leaves and latticed arches, tied-back curtains and clouds. One's toes—and perhaps a sail or two on the water—are the only intrusions on the scene.

Our own adjoining suites, done entirely in white (the original black-and-white floor tiles peeked out beneath the new), shared a large pool, as well as a full kitchen that hummed with activity early the next morning. A breakfast table was set for us on the porch, and it was here that we were introduced to ackee, a tropical fruit (Blighia sapida) native to Africa. Ackee is firm but soft—tofu-like—and is sautéed with salt cod, onions, and tomatoes to produce the Jamaican national dish, "ackee and codfish," a salty, nutty, fishy, and delicious stir-fry that resembles scrambled eggs. Like bagels and lox, it's perfect brunch food.

Christie, the pool tender, noticed our interest in the citrus trees that grew around the pool and offered to take us on a botanical tour of the property. The predominant specimens included green oranges and yellow limes, bougainvillea, avocado, ginger lily, hibiscus, and our newfound friend ackee—whose fruit is an almost fluorescent scarlet red and must be carefully harvested and prepared to be edible.

Although it was tempting to remain in our roost and request one of the resort's chefs to cook for us, we emerged later that day to check out the dinner scene at the beachside cabana. The remodeled bar delivered on the kind of Newport-style elegance we had heard about, with white-jacketed waiters, a bar resembling the deck of a vintage Chris-Craft, boldly striped upholstery, and framed photos of Round Hill family and visitors, including Paul McCartney, Demi Moore, and Bob Hope.

We'd arrived early for dinner, so we lingered at the bar, nursing rum punches. Suddenly, a piercing voice shattered the quiet cocktail din.

"Excuse me!" a woman shouted across the room at a waiter taking a couple's drink order. She wore a sheer beach sarong with a matching bikini and head scarf. "Those chicken skewers we had Tuesday?"

The waiter looked up from his pad.

"Get me some," she said. "Now."

It was the first time that we wished the front gate had been more effective.

Things had lightened up considerably by dinnertime, which at Round Hill invites something swankier than flip-flops: a few women had put their hair up, a couple of men had willingly donned jackets. We managed to insinuate ourselves into a group of "moms gone wild" (their words), three young ladies from the New York area who had left husbands and children behind for a weekend of reading and massages in the Caribbean. As we all dug into escabeche—snapper with pickled onions and peppers—and lobster, a reggae quartet of senior citizens serenaded the table. Be sure to have the name of your favorite reggae classic at the tip of your tongue; if you don't, the default is "No Woman, No Cry."

The drive into Negril the following morning represented a comedown from the beauty of Round Hill; the lavender bunkers of the Rui resort were followed closely by a nightclub compound called the Jungle and a concession that rents chopper motorcycles by the hour. But our own hotel, on the far side of town, was something else entirely, a hip resort for design mavens, as imagined by Fred and Wilma. The walkways and the octagonal, thatched-roof huts at the Rockhouse Hotel are constructed of a bright sand-colored stone with the texture of coral. The villas sprawl along craggy, wave-swept cliffs; next to the chaise longue on the terrace of our lodging was a narrow staircase that led into the Caribbean 20 feet below, where we could enjoy a refreshing mid-afternoon snorkel among the coral reefs.

Negril is a town with a partying spirit, and at the Rockhouse—which has a guard gate but no guard we ever saw—the social center is the hotel's restaurant, an indoor-outdoor terrace cantilevered over the water. The menu brings local food up to date in smart, refreshing ways: a crisp, oniony conch fritter came with a papaya-and-lime salsa that was bracingly sweet and tart. Fried red snapper was beer-battered with Red Stripe, and—finally!—on each table was a bottle of the condiment Pickapeppa, an aged purée of tamarinds and Scotch bonnets that to our minds is Jamaica's best, and most overlooked, export.

Ten minutes into our meal, the proprietor of a shop across the street dropped by the tables, introduced himself as Beezy, and offered us island exports of a more rarefied sort.

"I got good ganja, good blow, good jerk chicken," he said. "One-stop shopping, mon."

We took a rain check and made a beeline for the infinity pool. If overtures from local merchants are the trade-off for not feeling penned-in, we figured we could handle it.

Soaking up to our chins, we listened in as the staff hustled around in white polo shirts, delivering fruity drinks to a party of creative types from an ad agency who were nattering on about "the Volvo shoot." Where Goldeneye seems to court an aging jet set of rock-and-rollers and supermodels, and Round Hill an old-money, spa-and-golf crowd, Rockhouse's free Wi-Fi and pulsing sound track caters to young swells who network as hard as they play. Take away the thatched roofs and the coral, and we might have been on the roof deck of the Meatpacking District's Soho House.

And that's the vibe of Jamaica now. Like resorts in the Caribbean at large, properties here have the will, not to mention the prosperity, to specialize. Each has refined its amenities to home in on a distinct contemporary lifestyle; one resort, fresh from a renovation and eager to show its new-money bona fides, boasts of having Italian Mascioni linens as well as Jamaica's first caviar bar (with a Veuve Clicquot partnership, of course).

With the hustle of Negril behind us, we drove south along the coast road, into more pastoral land, a hill country of sugarcane and scallion fields. As the scenery became more rural, the roads counterintuitively widened. Near Treasure Beach we took a detour north, to Middle Quarters, to find the fiery "pepper shrimp" the town is famous for.

At the end of a mile-long avenue of bamboo was Howie's, a long, low shed with a dozen steaming, smoke-blackened steel cauldrons set in a row, each balanced on its own tripod of rocks over a few burning logs. Several cooks tended pots of conch, fish, and oxtail. When we asked for pepper shrimp, a gaunt man named Peckes consulted a woman named Vila, who picked up a cordless phone and placed an unintelligible call.

"Soon come," she said. "Soon come." We ordered bowls of a sweet, almond- and-bay-leaf-scented peanut porridge, but 15 minutes later, there was no sign of shrimp. Vila made another phone call.

"Soon come," she repeated. "Soon come." Ten minutes passed. As we were on the brink of leaving, a tall woman emerged from a house on the hill.

She introduced herself as Margaret Stone and set down a large stainless-steel bowl heaping with flaming red "shrimp"—large river crayfish that looked like tiny lobsters. Stone shoveled a pound into a black plastic sack, along with "extra spoonfuls for waiting."

The shrimp had been stir-fried with minced Scotch bonnet peppers, coarse sea salt, pepper, and vinegar. They were spicy, sweet, and addictive, and they may just be the most delicious—certainly the messiest—car snack ever.

The south coast was the part of Jamaica hardest hit by Hurricane Ivan last September, and on our way to Treasure Beach, we saw gaping fissures where the rushing water had dug into cracks in the roads. The cattle ranches and open fields seemed to bustle with activity despite the area's sleepy reputation. Then again, we'd also heard that Jake's, our next resort, was a quirky place. The vintage car sitting on four flat tires at the entrance seemed more ominous than inviting.

We needn't have worried. A welcoming party—a gang of lazy Jack Russells—had assembled around the front desk, and at the bar, Dougie Turner, who's been pouring drinks at Jake's for 12 years, was mixing perfect margaritas using yellow limes. An angler who lives two coves down was ready to whisk us out for some fishing in his boat, One Love. That night at dinner, a neighborhood wood-carver dropped by our table and showed us two beautiful busts he'd carved from polished pimento wood. A self-proclaimed wise man, he seemed more interested in trading proverbs than closing a sale.

Our villa was a tiny one-room shanty perched on stilts over the shore break, with window and door frames made of driftwood, brightly colored glass bottles embedded in the stucco walls, and a padlock and chain holding the door fast, if you cared to close it at all.

There are only 15 villas at Jake's, the most luxurious of them miniature Moroccan-inspired riads with rooftop decks and canopied harem beds, but none have televisions or telephones. And while the resort's bohemian whimsy seems to attract a young crowd, it's the kind that happily leaves the BlackBerry and the laptop behind. By comparison with the Rockhouse, the scene here was serene: a small pool fed by ocean water, a scattering of Adirondack chairs.

There's an organic quality to the place, which makes sense. Sally Henzell, the hotel's co-owner, was born and bred in Treasure Beach and raised her son, Jason, and daughter, Justine, there. The siblings are taking Jake's into the 21st century, but instead of banking its future on first-world luxuries, they're updating it with the annual Calabash Literary Festival and guided tours of Treasure Beach's roadside pubs.

Of all the hotels we stayed at on Jamaica, Jake's was unique in seeming to grow out of the place rather than imposing itself upon it—a fact that made for its own kind of intrigue. On our last night, when we returned from dinner, as our key turned in the padlock we heard a rustling in the bushes. Like 007, we flattened ourselves against the shadows of the eaves, breathlessly waiting for the intruder to make a move. And then, over a stone parapet, came one claw, then another, of a very large crab, making its way back to the sea.