Here are two stories about young “Georgie” Bush that you may not have heard, but which are worth recounting as he travels the globe as a world leader.

As a boy in Maine, he was the oldest of many cousins and would set the rules for summer games at the family compound. “If he was losing he’d change the rules — or take the ball and leave,” one cousin told me. Then there was the time when, as a new kid, just up from Texas at his prep school Andover, Bush was tripped and mocked early in an intramural soccer match. He waited for a chance to exact revenge — then blindsided his foe so viciously he nearly broke the boy’s ankle. “He spent that match angling to take me out,” said the Andover alum, now a successful businessman. “And he did.”

I was reminded of these adolescent tales by the recent disclosure of Doug Wead’s surreptitious tapes of conversations with Bush in the late 1990s, when Dubya was preparing to run for the Republican nomination. I was spending a lot of time in Austin back then, trying to get a fix on the then-governor of Texas. The tapes are confirmation — the clearest and best so far — of the sense I got of him at the time: that, far from being the dim-bulb tool of Karl Rove’s genius, Bush was a shrewd, prickly, win-at-all-costs guy who never should have been underestimated — as he was, for a decade — by the tottering Eastern power structure that dismissed him as a foolish, errant son of privilege.

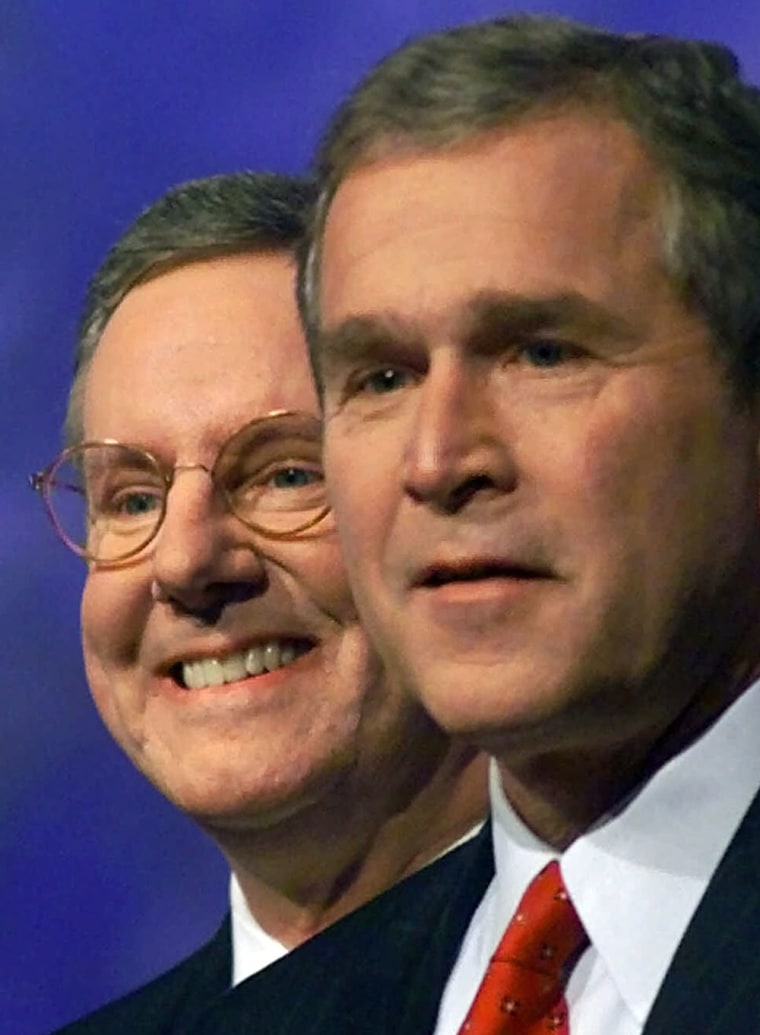

I recommend the Wead tapes to Jacques Chirac and Harry Reid — not to mention the mullahs in Iran.

Predictably, commentators poring over this Rosetta Stone have focused on the hieroglyphics about drug use in the ’60s (Bush is a little more candid in private than he was in public) and his careful (but not too public) wooing of evangelicals.

Far more revealing are the glimpses into the combative, even arrogant heart of Bush’s character — and that of the Bush Clan. These are people expert at boarding-school blasé, at hiding a seething need to win behind a veil of bumbling nonchalance.

At the time of the tapes, the governor of Texas was worried, almost obsessed, by the threat posed to his chances by a guy far richer and ideologically vetted than he: Steve Forbes. A key to Bush’s strategy was to scare others out of the Republican nomination race by amassing a hoard of contributions and endorsements, and by drying up those resources for the other candidates. The idea was to render the race a fait accompli before it even started.

It was easy to muscle the hapless Dan Quayle. As Poppy Bush went around quietly soliciting contributions for his son, the elder Bush let it be known that the Family would track gifts to other candidates, including Quayle. The former vice president had little chance in any case, but the Bushes were not taking chances. “They stepped on his air hose,” a Quayle adviser later told me.

But there was no stepping on Forbes. The guy had untold millions of dollars of his own, a geeky fearlessness that made him oblivious to threats and close, deep ties to the libertarian wing of the conservative movement in the GOP. Forbes’ dad made life miserable for Bob Dole in the ’96 Republican race, and Bush was worried that he might well do the same to him in the year 2000.

Bush’s response? To Wead — who might pass word along to Forbes — Bush threatened to take his ball and go home, then wait for the moment of payback. Were Forbes to win the GOP nomination by attacking him too hard, Bush told Wead, he could forget any support from the Bush family, including from his brother Jeb, the governor of Florida. Forbes “can forget Texas,” Bush tells Wead. “And he can forget Florida. And I will sit on my hands.” In other words, Bush would rather see the Democrats win the White House than a Republican who humiliated him by defeating him in the nomination race.

While he fretted that Forbes might play too rough, it was of course OK for Bush himself to do so. Taking the measure of Al Gore in the summer of 2000, demonizing him as “pathologically a liar,” Bush was getting an angle on his foe — and cited family tradition. In 1988, then Vice President George H.W. Bush ran a campaign that used cultural “wedge” issues to savage the candidacy of Democrat Michael Dukakis. “I may have to get a little rough for a while,” Bush the Younger tells Wead. “But that is what the old man had to do with Dukakis, remember?” Of course he remembered: Dubya and Wead had worked together on that campaign.

But the key words are “had to do.” No Bush wants to play rough, of course. But to win — or at least maintain their dignity and pride — they have to.