The story of an embattled professor at an equally embattled university has broadened into a debate about free speech and academic responsibility after administrators at the University of Colorado stepped up enforcement of an 84-year-old state law requiring professors to sign loyalty oaths to the U.S. and state constitutions.

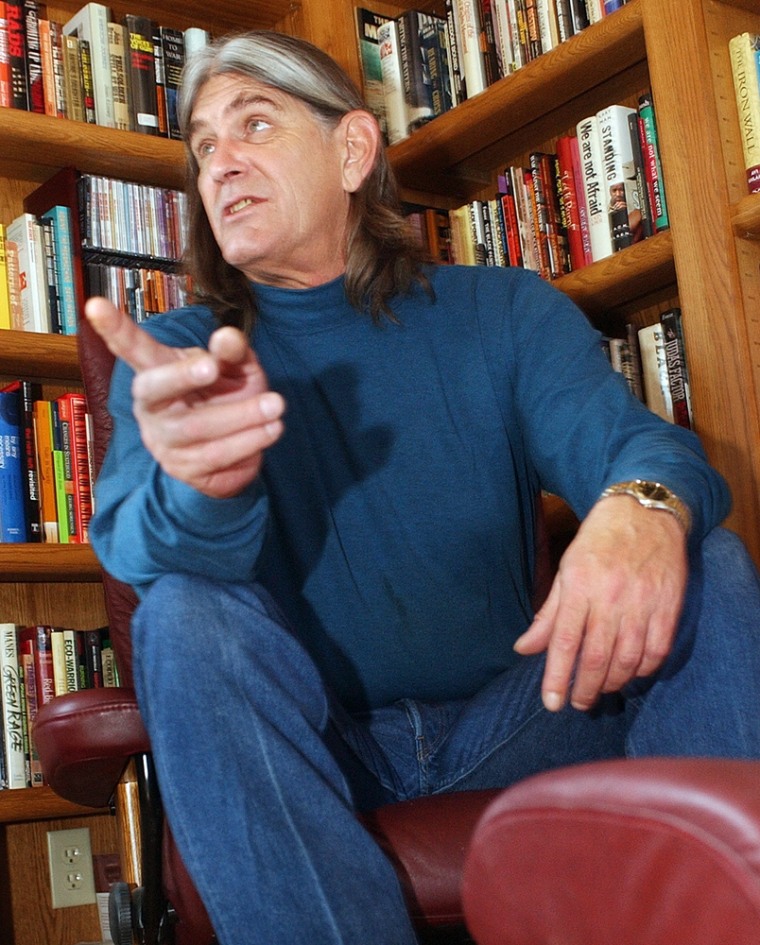

The controversy grew out of comments made by Ward Churchill, an ethnic studies professor at the university under fire since January over an essay he wrote about some of the Sept. 11 victims at the World Trade Center.

In the essay, Churchill said the Sept. 11 attacks should have come as no surprise because some people at the World Trade Center were part of “a technocratic corps at the very heart of America's global financial empire.”

And he referred to some of those who died on 9/11 as “little Eichmanns,” a reference to Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi SS official and an architect of the Holocaust.

The university administration denies the enforcement of the 1921 law requiring professors to sign loyalty oaths is politically motivated, or directly related to the Churchill controversy, insisting that the demand is consistent with university practice and state law. An official said the newly aggressive enforcement of the law was made necessary after a survey of loyalty oaths found some that were “misfiled or nonexistent.”

But many of the faculty at the 26,000-student university in Boulder, northwest of Denver, have bristled at the enforcement effort and alleged that the demand for re-signed loyalty oaths is nothing more than a political sop to those angered by the Churchill furor.

It’s the latest blow to a university trying to rebound from allegations of rape and student drug use amid last year's CU football recruiting scandal, and reports of rampant binge drinking among students.

Professor under fire

The gathering impact of the Churchill matter as well as the earlier recruiting scandal were among the reasons for the March 7 .

Churchill, whose work is under review by university officials amid calls for his firing, apparently had not signed the loyalty oath as required when he was tenured in February 1991. After the review uncovered the omission, he signed it on Feb. 18, a few weeks after resigning as ethnic studies chairman as the outcry over his essay gained momentum.

Pauline Hale, a spokeswoman for the university, said the loyalty oaths became a campuswide issue “when the university was unable to locate the signed oath of Ward Churchill, and in the process became concerned that there may be other faculty members’ reported oaths that may not be able to be located.”

‘It's enforced loyalty’

While the university has not accused Churchill of disloyalty to the U.S. or state constitutions, some longtime professors who signed the oath when first hired see the university's administration's current drive to apply the law as politically motivated.

“It's enforced loyalty,” said Paul Levitt, a longtime CU English professor. “I have taught at this university for 40 years and have shown in innumerable ways that I don't intend to overthrow the university. Now to be asked to show proof that I will kiss the hem of the queen's gown ... it’s too much. I'm always suspicious of oaths signed in times of hate, fear and repercussions.”

What rankles Levitt and other professors who’ve made their feelings known in faculty and staff newspapers and a blizzard of interdepartmental e-mails, leaked to a variety of Web sites, is a sense of linkage between the Churchill controversy and their loyalty to state and country. They hold the belief that application of the law has been inconsistent, and shot through with political overtones.

‘Climate of threat and fear’

“There's a political component to it, of course there is,” Levitt said. “There are people very unhappy with what [Ward] Churchill said, and this washes over the faculty. It’s done in the context of a very provocative situation. It's done in a climate of threat and fear.”

The university set Feb. 25 as a date for professors to confirm whether they had signed the oath when originally hired, as required by a law enacted in the waning days of the Red Scare of the early 1920's. While faculty members insist the Feb. 25 date was a deadline — one underscored with the threat of dismissal for non-compliance — university officials say that date was only an informal target date for professors to comply.

Hale said that compliance with the law was almost complete. “It appears that about 95 percent of the oaths have been located or are being re-executed by faculty,” she told MSNBC.com.

Still, there's the lingering suspicion among faculty of having been manipulated.

Levitt told MSNBC.com he had secured a lawyer before Feb. 25, and was threatened with termination later that day because of the university's inability to find his original signed loyalty oath. But after he refused to re-sign the oath, Levitt said he was told that “my original has been found. They found the records in 24 hours. I can't prove it but I'm convinced it's because we hired a lawyer and threatened to take it to court.”

Elissa Guralnick, an English professor at the university since 1973, agrees.

“I think they knew where these oaths were all along.” said Guralnick, who refused to re-sign her oath and who also consulted with a lawyer before Feb. 25.

‘A chilling effect’

“Why are they looking for everyone's oath? Presumably because ... conservative university officials have been wanting to get them signed,” she said. “Surely this all came up now because of the controversy over Ward Churchill. It’s a kind of harassment, an intimidation of the faculty.”

“We have a professor singled out for unwise speech, what I thought was a kind of vicious rhetoric,” she said. “But he has a right to say it and to express his opinions on political issues. The reintroduction of loyalty oaths has to have a chilling effect on the faculty.”

Hale rejected the assertion that the university knew where the records were all along and laid blame for the problem on “a decentralized approach to record keeping which has taken some time to review.” She said the disclosure of the missing loyalty oaths was made “just within the last couple of weeks.”

“Once we found there could be a problem, we felt obligated to respond,” Hale said. “It has been difficult to get a handle on what's there and what’s not. The chancellor said we will make changes in our process to avoid this from ever happening again.”

Hale also denied there were any political motivations in the university's action. “I haven't heard of anyone looking at this from a political point of view, but from the view that it is a requirement,” Hale said.

Jonathan Knight, director of the American Association of University Professors program on academic freedom and tenure, said obtaining loyalty oaths for public employees — from college professors to the president of the United States — is itself unremarkable.

A question of timing

“These kinds of oaths, sometimes characterized as oaths of affirmation, are found in a lot of states and they rarely occasion any controversy,” he said.

But like many of the Colorado faculty, Knight found the timing of the Colorado administration's request curious.

“I can understand why some of the faculty at Colorado are scratching their heads as to why they're being asked to do it at this time,” Knight said. “The question that arises is, taking the administration's explanation at face value for the moment, what made them look into this in the first place? Why has this issue arisen now? I don't recall a single instance of an administration of a public university saying to faculty, ‘We're concerned that folks didn't sign the oath, please sign it now.’”

Loyalty oaths have a long history in the United States. From the late 1940s to the mid-1950s, more than 40 states passed laws requiring loyalty oaths from their public employees. About 13.5 million Americans signed loyalty oaths as a condition of employment during the 1950s, The Washington Post reported last year.

And they’ve withstood legal challenges: Colorado's own loyalty oath — and the university's authority to terminate faculty members who don't sign it — was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1970.

Though the flap over the loyalty oaths appears to be quieting — the university apparently has not taken any action against non-signers since the Feb. 25 deadline — Churchill remains a divisive figure even on the lecture circuit, with free-speech supporters rallying to his defense.

In statements on Feb. 4 and March 3, Dr. Stephen M. Jordan, president of Eastern Washington University, canceled an April 5th speaking engagement by Churchill on campus, citing “safety and security issues.”

A future under review

Churchill has said he intends to appear that day on the Cheney, Wash., campus anyway. “I intend to be there,” he said in a Feb. 28 e-mail to supporters. And on Thursday, Native American students there held a rally in support of Churchill and academic free speech.

The latest twist in the Churchill saga may hinge on academic responsibility. Last week a Colorado newspaper, the Rocky Mountain News, reported on allegations of plagiarism against Churchill for content of an earlier essay.

The university’s Board of Regents and Acting Chancellor Philip DiStefano are reviewing Churchill’s academic record, and weighing the merits of the plagiarism allegations. The results of the review are expected to be released March 28.