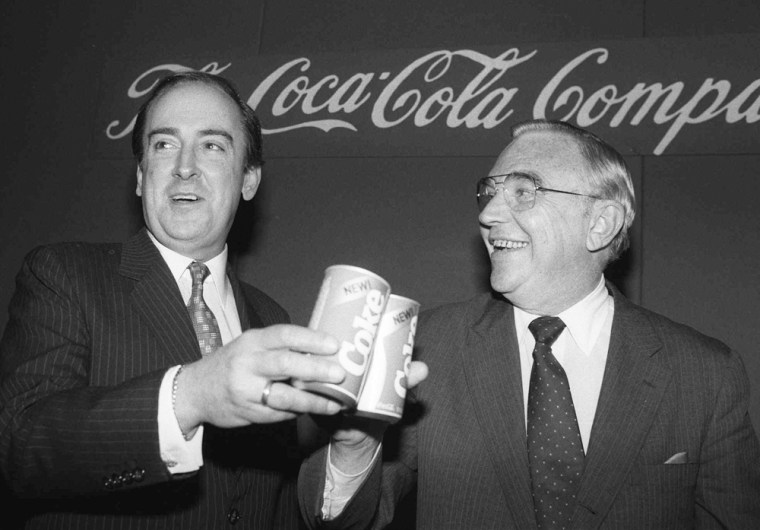

It was early 1985, and the news was slowly leaking out: The Coca-Cola Co. was working on a new kind of Coke, a variation of a product that reached back through American history, a rejoinder to the emerging challenge from an upstart called Pepsi.

The company, already two years into taste tests and research, was working with the secrecy of a military operation.

Then on April 23, New Coke was launched with fanfare, including prime-time TV ads. Company Chairman Roberto C. Goizueta proclaimed New Coke “smoother, rounder yet bolder,” speaking of it more like a fine wine than a carbonated treat.

But public reaction was overwhelmingly negative; some people likened the change in Coke to trampling the American flag.

Sounding retreat

Soon people were hoarding cases of the old stuff. In June 1985, Newsweek reported that savvy black marketeers sold old Coke for $30 a case. A Hollywood producer, giving an old vintage its proper respect, reportedly rented a wine cellar to hold 100 cases of the old Coke.

On July 11, Coca-Cola yanked New Coke from store shelves. “We did not understand the deep emotions of so many of our customers for Coca-Cola,” said company President Donald R. Keough.

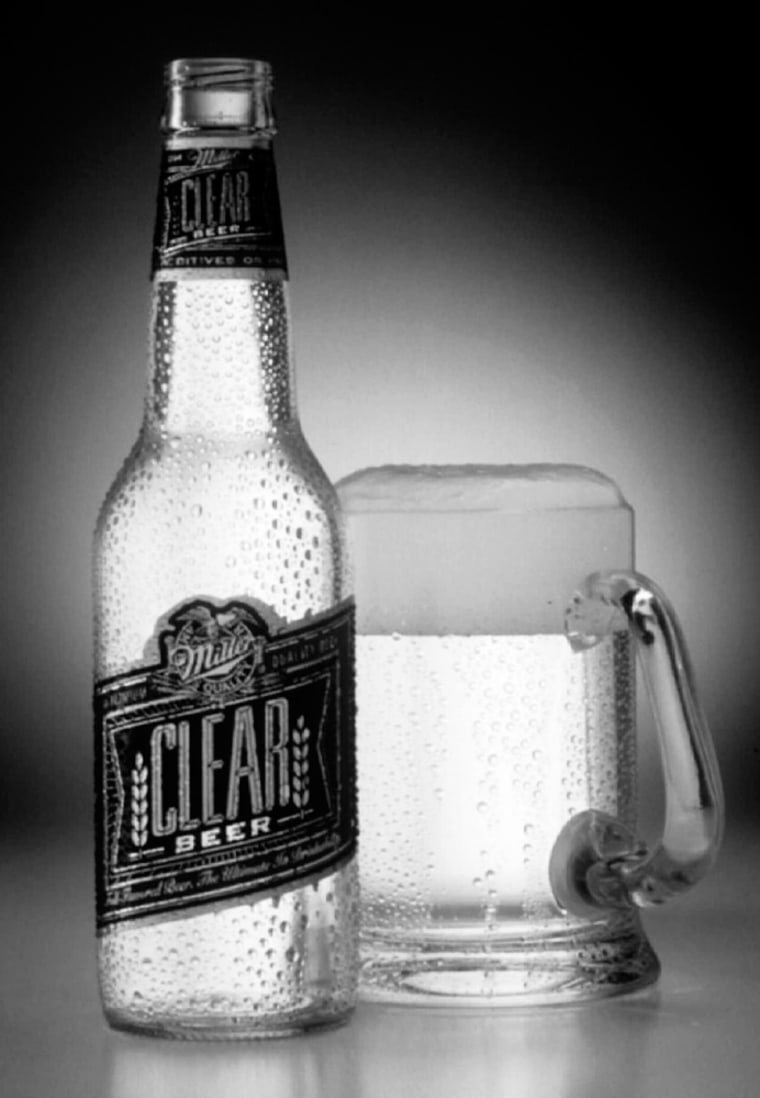

New Coke thus joined rabbit jerky, clear beer and the eight-track tape in the pantheon of marketing goofs, products that seemed like good ideas at the time.

Sam Craig, professor of marketing and international business at the Stern School of Business at New York University, pointed to what he and other industry observers have long considered a fatal mistake on Coca-Cola's part. “They didn't ask the critical question of Coke users: Do you want a new Coke? By failing to ask that critical question, they had to backpedal very quickly.”

On the 20th anniversary of the New Coke debacle, the original beverage is still going strong: The company's fourth-quarter net profits in 2004 were $1.2 billion, up 30 percent from the same period the previous year.

The rabbit (jerky) died

For all the populist rage leveled at Coca-Cola over New Coke, the company is hardly alone in making big marketing mistakes. Two Clairol shampoos, Look of Buttermilk and Touch of Yogurt, were soundly rejected by consumers who didn't want food in their hair.

Or consider the rise and demise of rabbit jerky. Despite sound nutritional reasons why the product should have been a success — rabbit contains a lower percentage of fat, less cholesterol than other meats and about as much protein as beef — it was a nonstarter.

Though rabbit meat still does brisk business as a specialty item, Americans with visions of Brer Rabbit, Bugs Bunny and the cute symbol of Easter couldn't stomach jerky.

The clear years

The years 1992 and 1993 marked the very short era of clear, when liquid products of every description were transformed into a transparent state, from Miller's Clear Beer to Zima, a clear malt beverage (reintroduced by Coors in 2002) to Amoco's ill-fated Ultimate line of clear gasoline blends, marketed with the slogan, “Your car knows."

The clear products more or less surfaced together, and more or less died together as well. Pepsi-Cola got its own cola comeuppance when Crystal Pepsi, a clear version of its trademark brand, fizzled in the stores, as roundly dismissed by consumers as New Coke was five years earlier.

Why do some products die despite the best intentions of their creators?

“In some instances, the product’s overchampioned,” Craig said. “Someone believed the Edsel or the eight-track tape or RCA’s videodisc was going to work, and they staked their careers and reputations on it, and kept pushing it in spite of misgivings.”

“Or maybe the research was beginning to suggest this wasn't a good idea — or they didn’t do their research,” Craig said.

“When you’re convinced you're right, you tend to ... push on regardless,” he said. “If it’s a bad idea, it doesn’t take long for the verdict to be reached.”

Unintended Consequences Dept.

Sometimes bad ideas, or bad luck, happen to good products. Ayds, a chocolate-flavored appetite suppressant candy, was one of the top-selling dietetic products through the 1960s and ’70s, but the name encountered problems shortly after the AIDS virus was discovered in 1980.

The product was eventually withdrawn due to declining sales and challenges of name association no amount of spin could stop.

Whether it’s Coke or candy, the disastrous reaction to a product also reveals the power of unintended consequences.

“Coke wasn't prepared for how the public responded,” said John Craven, editor of BevNet.com, a Web site that monitors trends in the U.S. beverage industry. “If you look at it, the success of New Coke was that it got people pissed off enough to care about regular Coke again.”

Try, try again

After the New Coke debacle, Coca-Cola returned to its original formula (hastily rechristened Coke Classic), then jumped headlong into a diversification of the original brand that continues today.

Coca-Cola's latest variations of the original beverage include Coke With Lime, being rolled out this quarter, and Coca-Cola Zero, a no-calorie variation of the low-calorie variation.

The new drinks follow on the heels of Diet Coke With Lime, introduced last year, which followed vanilla, cherry and lemon variations.

For a company whose flagship product once boasted of being “the real thing,” the mind-boggling number of tweaks on the iconic product might seem confusing. But one marketing expert said Coke's strategy is part of an industrywide marketing process.

Carving out ‘emotional territory’

“Companies want a mega-brand, a master brand that has a certain emotional territory that they own,” said Marilyn Raymond, managing director of New Product Works, a brand and marketing consultancy based in Ann Arbor, Mich.

“Our branding and our buying are emotionally connected," she said. "Out of that emotional territory companies can have different line extensions aimed at different targets. It's a perfectly rational way to expand your brand.”

And expansion has been a Coke trademark. In the years since New Coke went belly up, Coca-Cola has maintained the brand's luster where it counts: on the bottom line.

Coca-Cola ended 2004 as the leader in market share, with Coke Classic as the No. 1 carbonated soft drink in the United States.