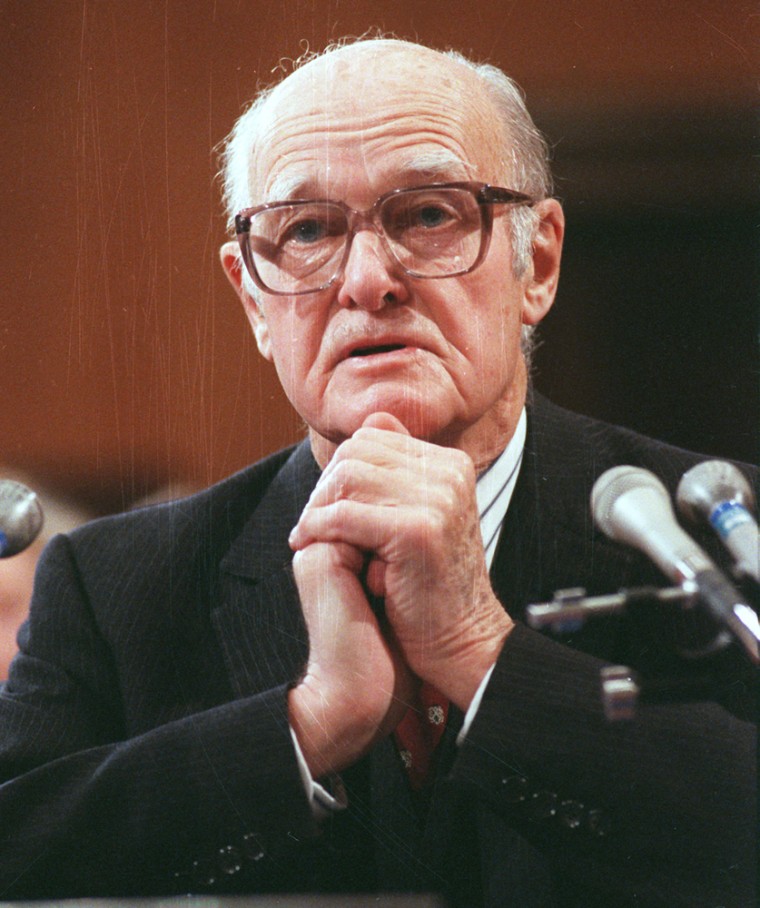

Diplomat and Pulitzer Prize-winning historian George F. Kennan, who gave the name “containment” to postwar foreign policy in a famous but anonymous article, died Thursday night at his Princeton home, his son-in-law said.

Kennan was 101.

“He was a giant. Many people have called him the most important foreign service officer of the past half-century,” said son-in-law Kevin Delany of Washington, D.C. “He was a very thoughtful man with an elegant writing style.”

Identified only as “X,” Kennan laid out the general lines of the containment policy in the journal Foreign Affairs in 1947, when he was chief of the State Department’s policy planning staff. The article also predicted the collapse of Soviet communism decades later.

“It is clear that the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies,” Kennan wrote.

When the Communist Party was finally driven from power in the Soviet Union after the failed hard-line coup in August 1991, Kennan called it “a turning point of the most momentous historical significance.”

Disagreed with pillar of ‘Truman doctrine’

In his 1947 article, Kennan disagreed with the emphasis on military containment embodied in the “Truman doctrine.” That policy, announced three months before publication of Kennan’s article, committed U.S. aid in support of “free people who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressure.”

Kennan thought a Soviet Union exhausted by war posed no military threat to the United States or its allies but was a strong ideological and political rival. In later years, he came to believe that the arms race, waged on the U.S. side in the name of containment, had become the greatest threat to both the United States and the Soviet Union.

Despite the “X” article and his work in formulating the Marshall Plan, Kennan lost influence rapidly after Dean Acheson was appointed secretary of state in 1949. After a difference of opinion on Germany — Kennan favored reunification, his superiors did not — he took a leave of absence in 1950 to work at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton.

He was appointed ambassador to Moscow in May 1952 but was declared “persona non grata” within a year. He resigned from the foreign service in 1953 because of differences with the new secretary, John Foster Dulles.

Won two Pulitzers

During his years out of the foreign service, Kennan won the Pulitzer Prize for history and a National Book Award for “Russia Leaves the War,” published in 1956.

He again won the Pulitzer Prize in 1967 for “Memoirs, 1925-1950.” A second volume, taking his reminiscences up to 1963, appeared in 1972. Among his other books was “Sketches from a Life,” published in 1989.

Kennan returned to the foreign service in the Kennedy administration, serving as ambassador to Yugoslavia from 1961 to 1963. In 1967, he was assigned to meet Svetlana Alliluyeva, the daughter of Josef Stalin, in Switzerland and helped persuade her to come to the United States.

In the 1960s, Kennan opposed American involvement in Vietnam, arguing that the United States had no vital interest at stake. In Kennan’s view, Washington had only five areas of vital interest: the Soviet Union, Britain, Germany, Japan and the United States itself.

George Frost Kennan was born Feb. 16, 1904, in Milwaukee. An uncle, George Kennan, was an expert on czarist Russia who wrote “Siberia and the Exile System” in 1891.

Princeton grad at 21

A year after graduating from Princeton University in 1925, Kennan entered the foreign service. Early postings included Switzerland, Germany, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

In 1929, Kennan was assigned to a program in Russian language, history and politics in Berlin. When the United States resumed diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union in 1933, Kennan accompanied Ambassador William C. Bullit to Moscow.

Kennan was assigned to Berlin at the outbreak of World War II in 1939, and was interned for six months after the United States entered the war in 1941.

During late 1943 and 1944 he was counselor of the American delegation to the European Advisory Commission, which worked to prepare Allied policy in Europe.

Kennan returned to Moscow and remained there from May 1944 to April 1946. At the end of that term, he wrote a long analysis of the prospects for postwar Russia, the so-called “Long Telegram,” which became the basis for the “X” article.

Helped guide Marshall Plan

In 1947, Kennan was appointed director of the policy planning staff of the State Department and directed much of the groundwork for the Marshall Plan, which helped rebuild Europe with a large infusion of aid.

Reflecting on the “X” article in 1987, Kennan wrote in Foreign Affairs that he now regarded the Soviet Union as a military threat but as no ideological or political threat to the United States — the reverse of the situation he perceived in 1947.

“It is entirely clear to me that Soviet leaders do not want a war with us and are not planning to initiate one,” he wrote.

In a New York Times article published in February 2004 as Kennan turned 100, former Ambassador Richard Gardner said: “All of us who aspired to careers in the Foreign Service still look to Kennan as a role model. Just look at the Long Telegram. How many ambassadors today could write such a document?”

Kennan’s honors included the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1989, Albert Einstein Peace Prize in 1981, the German Book Trade Peace Prize in 1982, and the Gold Medal in History from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters in 1984.

Kennan is survived by his wife, Annelise, whom he married in 1931. They had three daughters and a son.