International groups fighting the poaching of ivory accuse Sudanese officials of doing too little to stop a trade that is rapidly reducing the numbers of elephants in Africa.

But in sprawling Sudanese markets where ivory curios are sold, merchants complain the wildlife authorities are too diligent, if anything. They accuse officials of harassment by carrying out checks to see if they are selling legal, antique ivory. They are wary of speaking to a reporter.

One trader who refused to give his name said Sudan was a transit point for ivory from elephants poached in neighboring countries and bound for buyers in Asia. Another acknowledged that the markets, quiet this week, bustled when conferences or other events brought souvenir-seeking visitors to town.

The Sudanese government pledged last year to crack down on the trade by March 31. Sudanese officials did not immediately return requests for comment after one of the world’s foremost experts on the illegal ivory trade said earlier this week that the growing Chinese demand is creating a boom in Sudan’s ivory industry.

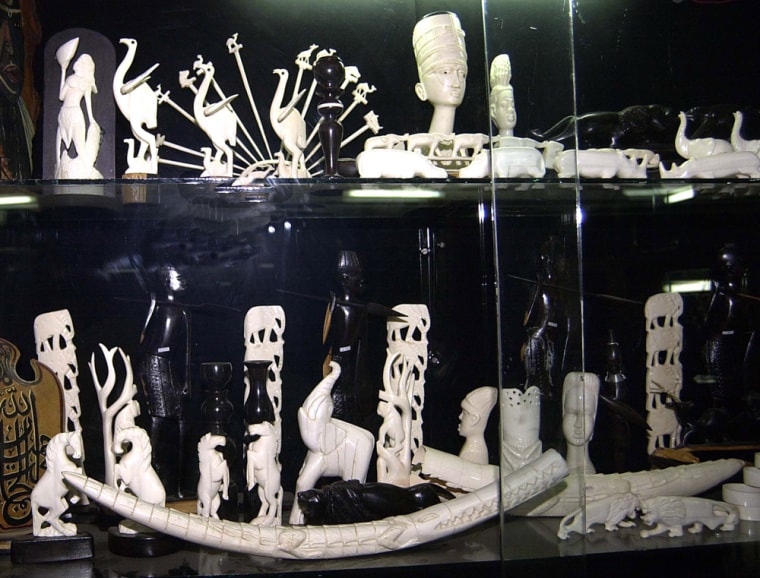

Survey finds 11,000 ivory items

The expert, Esmond Martin, said that during a visit to Sudan last month, he found traders and craftsmen openly displaying new wares. Martin, presenting his findings at a news conference in Kenya, said he and his team found 11,000 ivory products on display in 50 shops in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, and the twin city of Omdurman. He also visited 150 ivory craftsmen making new products, much of it jewelry.

The sale of most new ivory was banned in 1989.

“All the Sudanese need to do is enforce their own laws,” said Martin, whose research was financed by the British-based conservation group Care for the Wild International.

Martin, extrapolating from the amount of ivory he saw, estimated poachers were killing between 6,000 to 12,000 elephants a year to supply Sudan’s ivory markets. He said most of the elephants are killed in southern Sudan, Congo and the Central African Republic, with some ivory also coming from Kenya and Chad.

Network worried

A spokeswoman for TRAFFIC, a wildlife trade monitoring network, said Martin’s work confirmed its suspicions about Sudan, where a civil war just ended, and were similar to its findings elsewhere in Africa. Spokeswoman Maija Sirola said TRAFFIC would likely incorporate Martin’s work when it updates its own assessments.

TRAFFIC estimated late last year that between 4,300 and 12,200 elephants were needed each year to supply markets in Africa and Asia. It noted last year that its figures were conservative and based on studies that did not include Sudan and several other African countries. TRAFFIC had expressed concern that Sudan was not effectively controlling the trade in raw ivory or tracking the activity in its local markets.

TRAFFIC, like Martin, believes most of the poaching is happening in war-ravaged central Africa, where turmoil has made it difficult for researchers to find out what is happening to elephant populations. Sirola said the level of poaching, while high, was probably not threatening the survival of elephants as a species.

More than 50 percent of Africa’s elephants were killed by poachers between 1979 and 1989. That poaching was driven by economic prosperity in Japan, but the current increase in demand is a result of China’s growing economy, said Nigel Hunter, director of the Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants Unit of the United Nations organization that regulates trade in wildlife.

China on Tuesday denied it encouraged the illegal ivory trade. Hunter, the U.N. official, said the Chinese government has stepped up efforts to intercept illegal ivory imports, but that Sudan has done little to discourage the trade.

Chinese workers buy ivory

In Khartoum, ivory curios are stocked along with paintings and other local crafts in places like Souq Afranji, which is Arabic for Westerners’ Market.

Jamal Osman, who says his family has had its shop in Souq Afranji since 1917, said Westerners who once were his main customers no longer buy ivory, and Chinese and other Asians and Arabs aren’t interested in his antiques. The Chinese, he said, are looking for large, uncarved pieces of ivory.

Martin said ivory name seals and chopsticks were recently introduced to Sudan’s markets to meet Chinese demand. He said customers were drawn from the 3,000-5,000 Chinese who live and work in Sudan, mainly in the oil, mining and construction industry.

Osman said he sold only old ivory wares, like a bust of the Egyptian pharaonic Queen Nefertiti, which he said was carved in 1964.

“This is a family business and we have our records in shape,” he said. “However, I cannot talk for all people.”