I loved Saturday mornings when I was a kid. I usually watched cowboy shows— you know, the ones where they fired dozens of rounds each and never had to reload their 6-shot revolver, where the good guys wore white hats and the bad guys wore black.

Life was simple: If a white hat put the feet of a black hat to the proverbial fire demanding the truth “or else,” the bad guy would always roll over and spill his guts and the information obtained was always correct. The day was always saved.

But what about real-life torture? Does it really help us gain information from our enemies?

Interrogation— from Vietnam to Guantanamo Bay

My experience suggests it largely doesn’t. I was a Military Intelligence (MI) agent in Vietnam in 1966. I watched as we worked to dehumanize the enemy, some calling them “gooks,” “slopes,” and other terms designed to differentiate between them and us, the good guys and the bad guys.

The U.S. Army and other military services taught and practiced “IPW” or interrogation of prisoners of war techniques. A designation in your military service record verified that you had been taught to conduct “interviews” of enemy combatants. MI agents and other battlefield interrogators did what they believed they had to do to get information from a detainee, information that could save the lives of other GIs. After all, how could you compare the life of a Vietcong or a member of the North Vietnamese Army with that of an American, especially when our troops were being killed at such an alarming rate? And so it went, just as it had probably gone since combatants first squared off against each other with rocks and spears on the fields of battle around the world. We had to defeat “the enemy,” and if we needed to “take the gloves off,” we justified it in the name of war in order to bring our troops home alive.

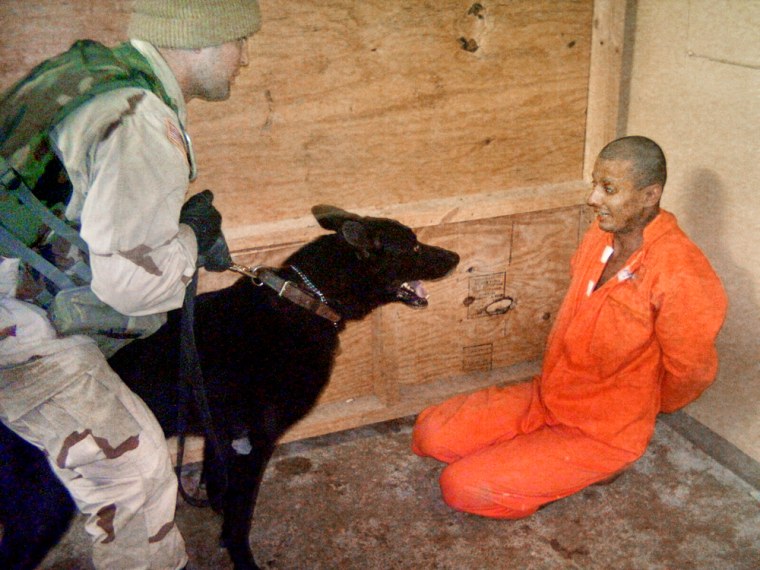

Now fast forward with me to 2003-2005 and the detainee holding facilities at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba and the infamous Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. We know that General Ricardo Sanchez, former U.S. military commander in Iraq, signed a memo in September 2003 that authorized interrogation techniques against Iraqi and other detainees that may have been in violation of both the Geneva Convention and the U.S. Army’s own standards for the conduct of such interrogations. Gen. Sanchez’s memo allowed for tactics such as the use of dogs (the Iraqi detainees were said to be terrified of attack dogs); subjecting prisoners to body positions that would induce physical and mental stress; the implementation of isolation techniques; manipulation of the prisoner’s environment, including disruption of his sleep cycle to confuse his body’s circadian rhythm; drastically changing the temperature in the prisoner’s cell, and even injecting “unpleasant smells” into the prisoner’s environment.

It now appears that the military chain of command broke down and the significant and substantial difference between interrogation and torture was somehow lost. Trained and untrained military and government interrogators conducted these interviews, including National Guard and military reserve personnel, and U.S. Government intelligence agents (read: CIA) and other government contract employees. We have all seen the pictures of prisoners stripped naked and made to lie on top of each other, detainees wearing a dog collar and leash being led around by a laughing female guard, and attack dogs allowed to approach and possible abuse prisoners. We have heard of other alleged abuses, including lit cigarettes put in the ears of prisoners and physical beatings that have contributed to or caused the death of dozens of the detainees— despite the fact that information linking the prisoners to known terrorist groups was said, at least in some cases, to be shaky at best.

Doing whatever it takes

If you’ve watched the TV series “24” this season, you’ve already witnessed a terrorist shot in the leg during an interrogation, another person shocked with an electrical cord, and yet another shot with a stun gun. All of those acts by or around Jack Bauer, the tough government secret agent and rebel you love to fear. Jack’s actions against others are justified, in part, by the ticking clock scenario, something that Jack’s show, by definition, seems to be up against every week.

“Do what you got to do Jack,” we yell, “to save us from destruction.” We have learned from Jack and others that we must do whatever it takes to preserve truth, justice and the American way of life. But if we follow Jack’s example and do “whatever it takes and to whom ever we must,” do we eventually lose the distinction between them and us, and, perhaps, reach the point one day, as Pogo once said, where “We have met the enemy and he is us?”

“Stress and duress” is the name for the practice of using coercive techniques to induce psychological regression in a prisoner by the systematic weakening of his will to resist. We do this to exhaust an individual’s ability to oppose our demands while providing him with the rationalization— perhaps the cessation of pain— to cooperate. But what about less brutal methods, say Sodium Pentothal? Unlike in the movies, there is no real “truth serum” that will cause a person to lose his psychological self-control and deprive him of the ability to lie or otherwise resist providing the information demanded from him. Drugs used in this manner are mainly intended to create a state of relaxation and make the person more susceptible to suggestion, but their use does not guarantee results that include the absolute truth.

The fact is that no “trial by ordeal,” be it physical, psychological or chemical will insure that we can: (1) actually get information from the detainee, and (2) guarantee that what ever information extracted is true, a reality with which most interrogation “experts” will agree.

But what forms of “ordeal” are acceptable and who decides, and how do we know that we’re dealing with an individual who truly possesses the information that we so desperately seek? If we have no guarantee of getting information, if we have no reason to believe what someone tells us under duress is true, if we are allowed to decide the limits of such stress and duress techniques on a local level without oversight, and if we’re really not sure that the detainee even has the information we want— is there justification for the use of torture, or does it just become summary punishment administered perhaps by immature, misguided and untrained individuals (at best), or by manipulative self-serving sociopaths (at worst)?

The FBI, which has been critical of such physically aggressive interrogation techniques at Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib, asserted in late 2003 that these tactics had failed to produce any intelligence that has assisted in the neutralization of any threat to date, something the military disputes. Another consideration is if a detainee was originally angry with us, and if he is tortured in these ways, how much angrier and more dangerous will he be when he is ultimately released from captivity?

Information concerning both the battlefield and terrorism comes in two forms: operational (that of immediate value) and strategic (that which is long-term in nature). Other than an eight-digit GPS grid coordinate that can be locked into a cruise missile with bin Laden’s postal address, or the location of Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction, or specific intelligence on the where and by whom of the next terrorist attack, the information that we can hope to obtain from the current crop of hundreds of Iraqi detainees and other prisoners (from over 40 countries) appears limited in nature. In other words, if we don’t get it right away, it is probably is of little or no use.

My bottom line

I’m the first to admit and even assert that there are extreme circumstances that require extreme measures. If you tell me that someone in our custody absolutely, positively knew the cave bin Laden is hiding in, or the location of the biological weapon that has been smuggled into New York City, L.A., or Tucson to be used in a day or two to kill tens of thousands; or if someone had information concerning the location of your kidnapped child or my grandchild, I’d do just about anything to anyone to get that information.

Our collective challenge is to find ways to obtain such information without adopting the same methods as those of our adversaries, and thereby losing our identity by letting our enemies make us just like them.

It appears that our ultimate question becomes how do we draw the line, save our child, win the war— and still justify wearing our white hat?

Email Clint at CVZ@msnbc.com

Clint Van Zandt is an MSNBC analyst. He is the founder and president of Inc. Dr. Van Zandt and his associates also developed , a Website dedicated "to develop, evaluate, and disseminate information to help prepare and inform individuals concerning personal and family security issues." During his 25-year career in the FBI, Mr. Van Zandt was a supervisor in the FBI's internationally renowned Behavioral Science Unit at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia. He was also the FBI's Chief Hostage Negotiator and in his current position, was the leader of the analytical team recognized with identifying the "Unabomber."