A new look at ancient craters on Mars finds five that are arrayed along an arc that's part of a giant circle around the planet. The circle may have been Mars' equator long ago.

The craters might all have been formed when one giant asteroid broke apart, its fragments slamming into the planet at different times and locations around the then-equator, says Jafar Arkani-Hamed of McGill University in Montreal.

If the analysis is right, it has implication for where water might lurk beneath the Martian surface today.

Ancient Mars

Mars was once warmer and wetter, several lines of evidence suggest. Scientists speculate that while much of the water evaporated into space, some may have penetrated underground and remains. Water is a key ingredient for life as we know it.

Like Earth, the poles of Mars have not always been where they are today. In fact, Mars seems to have transformed dramatically during its roughly 4.5-billion-year life. One striking feature known as the Tharsis Bulge — it's 5 miles high (8 kilometers) and covers a sixth of the planet — illustrates how a changing shape would have altered its axis over time, scientists say.

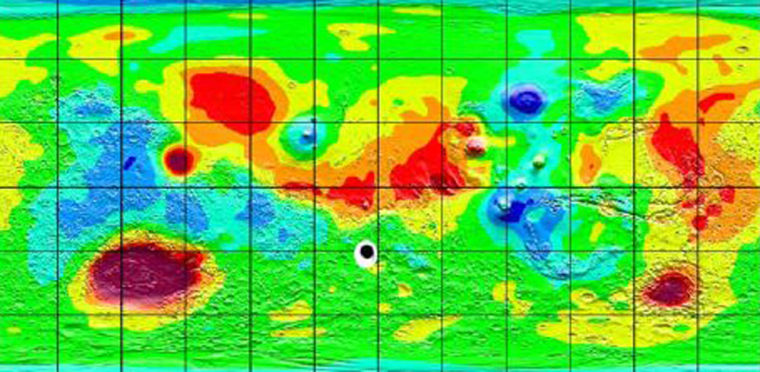

The five basins identified in the new study are Argyre, Hellas, Isidis, Thaumasia and Utopia. They were thought to have all formed prior to the development of the Tharsis Bulge.

Arkani-Hamed's calculations show the basins could all have been created by fragments of an asteroid orbiting routinely around the sun. Most asteroids, as well as all the planets except Pluto, hew roughly to the same region in space, an imaginary plane that extends outward from the sun's equator.

The asteroid may have been 500 to 600 miles in diameter (800 to 1,000 kilometers). It came too close to Mars at some point and gravity yanked it apart, the thinking goes. Later, the pieces hit the planet.

Flip-flop

The craters form a circle whose center is at latitude -30 and longitude 175, which Arkani-Hamed figures was once the south pole.

"The region near the present equator was at the pole when running water most likely existed," Arkani-Hamed said in a statement Monday. "As surface water diminished, the polar caps remained the main source of water that most likely penetrated to deeper strata and has remained as permafrost, underlain by a thick groundwater reservoir."

The bottom line: Future missions looking for underground water — and any possible life that might exist there — might bore into the Martian equator of today, where the ancient water could still reside.

The idea is presented in the Journal of Geophysical Research (Planets).