Scientists have discovered how to squeeze bubbles inside bubbles, which may offer a way to smuggle all sorts of substances — from expensive perfumes to cancer drugs — into places they couldn’t survive without protection.

The new method, developed by David Weitz of Harvard University and his colleagues, produces droplets in carefully controlled sizes, with multiple fluids nestling inside each other. The findings appear in Friday's issue of the journal Science, published by AAAS, the nonprofit science society.

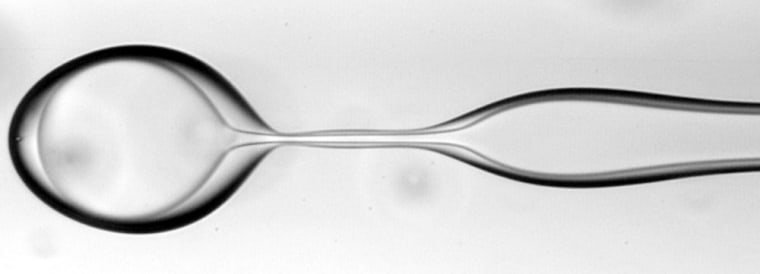

Double bubbles at work

Some of the most ambitious hopes for these multilayered droplets are in medicine, where it would be essential to control the amount of drug being delivered.

Hiding a drug inside droplets could serve several purposes. Researchers might design the droplet to allow the drug to seep out gradually once it’s in the body. Or, if a treatment has two components that need to be kept separate, they could be put in different layers of the same droplet.

Someday — with a lot more research — it may even be possible to tag droplets with molecules that make them stick to a certain site, such as a tumor, where they can slowly release cancer drugs. Other types of droplets might be filled with insulin and targeted to certain sites in the bodies of diabetics.

Researchers in other industries would also like to make multilayered droplets in precise sizes. This technology should be useful in cosmetics, for example, allowing specific amounts of expensive perfume or anti-aging enzymes to be added to beauty products without unwanted reactions.

Beyond salad dressing

The bubble mixtures the researchers created are called double emulsions. In regular emulsions, two “immiscible” fluids, like oil and vinegar, mix in such a way that one fluid forms droplets in the other. In a double emulsion, a core droplet is surrounded by a second fluid layer, so that the inner fluid is completely shielded from the outer fluid.

Typically, double emulsions are made by shaking two fluids together, like making a vinaigrette, and then shaking that emulsion with a third fluid. Until now, it’s been difficult to manipulate the size of the droplets.

“Double emulsions are a wonderful way to encapsulate things, but normally you can’t make them in a really controlled fashion,” Weitz said.

Weitz and his colleagues instead used a series of small glass tubes, the nose of one inserted in another. As the fluids from the inner tubes flowed into the outer tubes, they formed droplets coated by layers of each fluid.

Super solids

The researchers experimented further with polymers and resins, which could be solidified using light or heat once the droplet had formed. They also used polymers in a solvent and evaporated the excess liquids, producing tiny hollow spheres.

Using the polymers, Weitz’s team made permeable, double-layered capsules much like the “liposomes” that transport cargo around our own cells. Weitz’s co-author, Darren Link of Raindance Technologies, speculated that these types of structures might be used to encapsulate whole cells, such as insulin-producing cells. Then, if the shell material were designed just right, it might be possible to slip it into the body without provoking an immune response.

“People have thought for quite some time that cell encapsulation is one route to artificial organs,” Link said.

Many of the potential applications for double emulsions lie a long way off into the future. In the meantime, the new findings have given the Science authors insights into the physics, as well as the poetry, of how fluids move.

“It’s just beautiful,” Link said. “These beautiful shells happening one after another. Who would ever have imagined that you could make such perfect drops in drops? That’s what I like best about it. I think it’s art.”

For more "Mysteries of the Universe" from the journal Science, visit .