This month's embarrassing collision between NASA’s space robot and its target satellite may have a regrettable "space spinoff" effect as well. The Demonstration of Autonomous Rendezvous Technology, or DART, could focus renewed attention on the question of how easy it actually might be to deliberately hit a space target with a military "killer satellite" — and whether such a weapon was desirable, or needed to be barred by international treaties.

This issue has been simmering for a long time, but it is rapidly approaching a diplomatic boil as some U.S. military space tests, along with alarmist rhetoric, suggest that such weapons are just over the horizon. So blatant are the political agendas involved, and so technologically naïve are the warnings, that any reliable public debate seems hopeless.

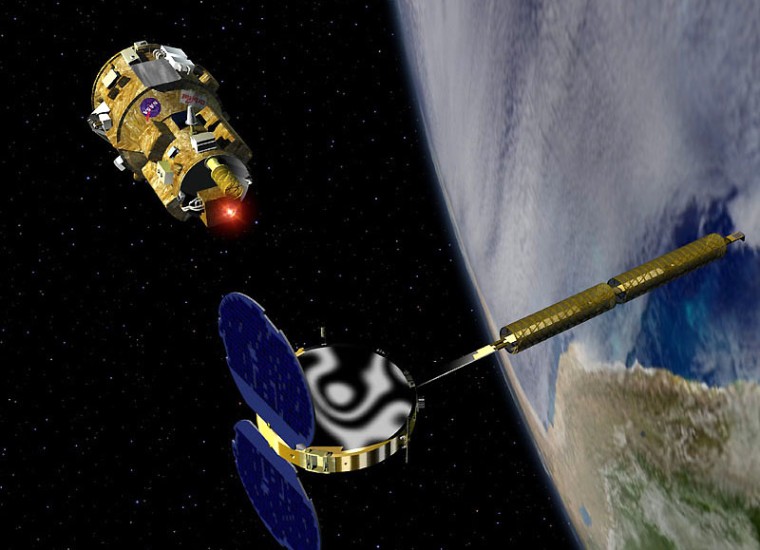

The DART spacecraft was supposed to approach and delicately circle a target satellite on April 15, but it apparently became lost and began blundering around blindly, quickly exhausting its rocket fuel. During the course of these wild swings through space, DART actually collided with the target, a small military communications testbed named "MUBLCOMM."

NASA officials did not release this information until journalists confronted them several days later with evidence received from space workers.

Runaway debate

Even before the launch, DART had been accused of being a cover for a space weaponization program directed by the Pentagon. Although space has been militarized since the very beginning with satellites that support earthside combat, and although surface-to-surface missiles travel through space along their paths, only on a few rare occasions has hardware actually been put into orbit to conduct direct combat. That’s what "space weaponization" has come to signify.

But is the test of a robot rendezvous satellite an unambiguous prelude to introducing such weapons? Space experts contacted by MSNBC.com unanimously dismissed such notions as unproven, unlikely and even in some cases preposterous.

Aside from the existence of several compelling non-weapon uses for such a robot rendezvous capability, these experts pointed out that other nations (such as Japan) and private corporations (such as Orbital Recovery Ltd.) are pursuing parallel development projects, none with any weapons application.

Some missions would refuel or repair unmanned satellites. Others would carry supplies to the international space station. When the time comes to bring back the first soil samples from Mars, the canister containing the samples must be linked automatically to a homeward-bound rocket in orbit around the Red Planet. Initial robot rendezvous test maneuvers at Mars are already being planned for later this decade.

But the theme of "space weaponization" is a challenging one, and the United States finds itself isolated on the issue for a number of reasons. Any hope of a logical resolution depends on a rational debate over U.S. capabilities and ambitions in space. DART’s accidental contribution to this debate will only make a bad situation worse.

The weaponization mantra

The DART collision came at a time of heightened suspicions about U.S. space technology tests. Besides DART, there is the XSS-11 military mission and even NASA's Deep Impact probe, aimed at deliberately colliding with a comet.

Another highly controversial weapons-related military satellite is called NFIRE, for “Near-Field Infrared Experiment.” The NFIRE launch was originally planned for last year, but has now been put off until late this year at the earliest. Designed to collect close-up readings of missile exhaust plumes from an orbiting observation point, it was to carry a satellite that dove in closer to the climbing rocket — arguably an “attack vehicle” against enemy satellites.

Russian news accounts tended to cast the DART exercise as a thinly veiled military exercise: In one article, Kommersant's Ivan Safronov and Gazeta.ru's Alina Chernoivanova reported that Russia’s Defense Ministry was “alarmed at the American experiments on autonomous rendezvous programs for spacecraft.”

According to the Russian journalists, NASA’s DART satellite “independently determined the location, and based on the silhouette identified the target” for its approach. The military satellite’s silhouette “was given in advance,” the article claimed (erroneously), and added that DART then performed a military-style ‘IFF’ (Identify Friend-or-Foe exchange of radio signals). This also was inaccurate.

Similar alarms were sounded by the newspaper Izvestia, the Interfax-Military News Agency and the RIA-Novosti news agency.

A failure to communicate?

Central to many of the recent Russian complaints have been words attributed to Lt. Gen. Henry Obering, director of the U.S. Missile Defense Agency. Writing for RIA-Novosti, Andrei Kislyakov’s essay reported that Obering “said new global threats highlighted the need to create space-based defensive systems.” In Obering’s opinion, according to Kislyakov, “orbital interceptors should become part of America’s ballistic missile defense program.”

Safranov and Chernoivanova wrote that Obering said "new threats that are appearing throughout the world indicate the need to create a space layer" of defensive systems. Their article went on to quote him as stating that "there is a lot of attractiveness to space-based interceptors."

But the words quoted in the Russian articles don’t jibe with accounts in U.S. news media. Some "garble factor" was introduced along the way, perhaps unconsciously.

According to the April 13 issue of Defense Daily, Obering’s reference to space-based missile interceptors was made in the context of the changing nature of the missile threat to the United States. “Emerging threats and uncertainty would really have us take a hard look at developing a space-based layer that we could add to the system,” he suggested. At some point later in the decade, he added, the U.S. intended to conduct flight tests “so we can explore options for space-based interceptors.”

He expressed uncertainty about using such systems in any future missile defense system, but in response to a question from the audience stated: “I’m willing to experiment.” Paraphrasing Obering’s response, journalist Ann Roosevelt wrote: “There’s a lot of ‘attractiveness’ to space-based interceptors.”

Note how the Russian version puts that entire sentence in quotation marks as if it were Obering’s exact words — which they weren’t. And his conditional expression of interest in trying new things if threats change over the years was turned into an unambiguous commitment to building exactly such weapons.

Reading things the wrong way

It turns out that the Russians were actually relying on an online interpretation of Obering’s statements. The Claremont Institute in California maintains a Web site advocating development of a missile defense system, and in a news report dated April 12, their site carried a report that was based on Roosevelt’s original story in Defense News.

“Emerging threats round the world indicate the need for developing a space-based layer,” the Web site quoted Obering as saying — which is much more definitive than the actual words in the article named as the original source. Further, Claremont’s story also provided the altered quotation later used in the Russian press: “There is a lot of attraction to space-based interceptors.”

The Claremont site does go on to provide crucial information on whether or not "space interceptors" were imminent — information that the Russian reporters who relied on it for the jazzed-up quotations omitted from their stories. Obering said that study contracts might be awarded in three or four years, but that as of now, his office “is not even seeking money for the project, until FY 2008.”

Chinese join in the confusion

The Russian reports aren't the only examples showing how comments that seemed clear enough in English suddenly wind up sounding alarming in a foreign language. Writing in the Beijing newspaper Jiefangjun Bao, Zhang Cao followed the same pattern when he asserted that U.S. policy was becoming one of attacking other satellites whenever interference was suspected with an American satellite.

“In current U.S. military regulations,” he wrote, “a satellite attack will be regarded as the initiation of war, and the response from U.S. armed forces will be to ‘counterattack.’ Thus, we can see from this ‘pre-emptive’ strategic thinking that it is very likely that the U.S. military will blindly use its counter-satellite weapons to attack satellites of an innocent country when a U.S. satellite breaks down due to the malfunction of major parts, and this increases the possibility of the ignition of an unexpected war.”

As proof of this, Cao quoted Maj. Gen. Daniel Darnell, commander of the U.S. Air Force Space Warfare Center, as saying, "If there is trouble with your orbiter, your response should be to 'think of a possible attack.'"

“This can be regarded as a hint by a U.S. official about the ‘pre-emptive’ strategy,” Cao concluded.

This conclusion appears to be a misinterpretation of Darnell’s advice that satellite trouble should be thought of as an indicator of a possible foreign attack on that American satellite. Darnell was clearly not advocating a hair-trigger counterattack whenever a U.S. satellite encounters trouble.

Technological truths

The level of confusion here doesn’t have to be disheartening. Unlike many other themes in arms control and general diplomacy, space weapons policy is subject to physical laws and engineering principles. This in turn allows conflicting claims to be measured and judged as to their practical credibility.

Take last year’s accusations about the NFIRE satellite. The Moscow Times said the test would mark a "sinister milestone," with the United States willing to break "a long-held taboo and launch the first weapon into the global commons of outer space." An ABCNews.com report called it the "first real step" toward the "unprecedented weaponization of space."

In reality, the test would have represented no such thing.

First, to calm down the Russian rhetoric: It's true that, over the years, both the United States and Russia developed ground-based anti-satellite weapons, some using air-launched missiles, some using components of existing anti-missile systems. But the only ones to test or deploy space-to-space weapons in orbit were the Russians. The United States did not respond.

Secondly, the idea that the NFIRE system could be used in an anti-satellite mode fails on the basis of the guidance technology. For anti-missile testing, a defensive weapon tracks the hot exhaust plume of the rocket in flight, or uses massive ground-based radars. An orbiting "killer satellite" based on NFIRE would have to look for free-flying satellites with no convenient rocket plumes streaming from them, and it wouldn’t have the electrical power to track a target at the range required for changing to an intercept course. The whole idea collapses under its technological impossibility.

The issue of basing weapons in orbit, whether for missile defense or satellite attacks, is well worth public and diplomatic debate. But spaceflight is such a tricky business, as NASA has taught us with lessons ranging from the Columbia shuttle disaster to the DART debacle, that the misinformation and misrepresentation threaten to make any reliable resolution impossible. So far, a rational debate on the issue of weapons in space has yet to be even launched.

James Oberg, space analyst for NBC News, spent 22 years at NASA's Johnson Space Center as a Mission Control operator and an orbital designer. He is also an expert on Soviet and Russian space policy and author of the book "Star-Crossed Orbits: Inside the U.S.-Russian Space Alliance."