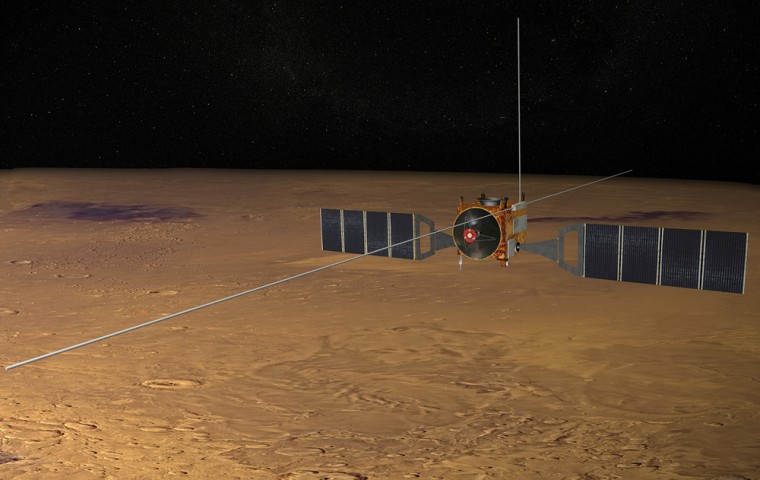

The European Space Agency says it is delaying the deployment of a second radar boom on its Mars Express probe because the first boom, deployed last week, didn't fully lock into position. If the glitch can be resolved, the radar could help solve the mystery of what happened to the Red Planet's ancient seas.

In a statement released Monday, the space agency confirmed earlier reports that it had begun the long-delayed deployment of its Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding, or MARSIS, last Wednesday. The first of three booms was successfully unfolded from its storage compartment on the spacecraft, but ESA said one of the 65-foot-long (20-meter-long) boom's 13 segments wasn't locked in place.

ESA did not provide any details about what the possible range of conditions might be. The boom might be actually safely locked but lacking the right indications, or it might be nearly in the proper position, or it might be far out of proper alignment.

Over the years, problems with deploying booms and antenna deployment have hit several satellites, sometimes with calamitous consequences. After the 1989 launch of NASA's Galileo probe to Jupiter, a deployment problem with the high-gain antenna severely limited the amount of scientific data it could send back, but the mission still achieved significant successes.

Figuring out what went wrong

ESA said it would hold up on unwinding the second 65-foot boom, as well as a third, shorter boom, pending an investigation of the anomaly.

"It was determined that deployment of the second boom should be delayed in order to determine what implications the anomaly in the first boom may have on the conditions for deploying the second," ESA said. "This decision is in line with initial plans which had allowed for a delay should any anomalous events occur during the first boom deployment."

The hollow fiberglass radar booms have been folded like concertina loops inside storage containers since before the Mars Express orbiter was launched in June 2003. The booms are supposed to spring into the desired shape from their compressed elastic forces when the outer doors on the MARSIS experiment are opened.

Worries over undesired thrashing or fouling of the booms had put off ESA's original plans to unfold them in April 2004, shortly after the probe reached its final orbit around Mars. It's remotely possible that keeping the booms folded much longer than planned, through many day-night cycles in orbit around Mars, may have had subtle weakening effects on the structural material.

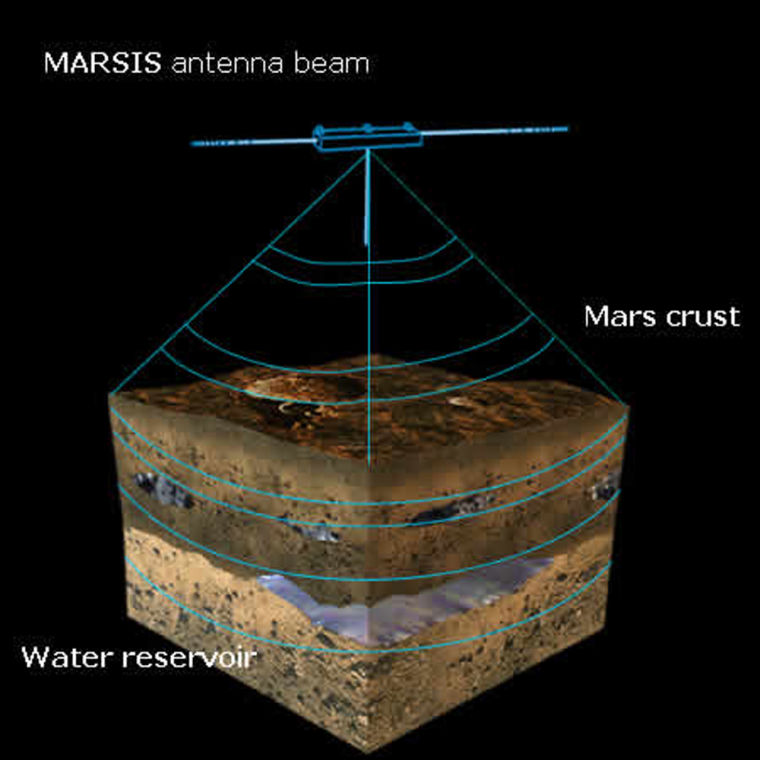

Even if all three booms are rolled out successfully, the MARSIS experiment would have to be tested for several weeks. Only then would the radar antenna's 15-watt transmitter begin its scientific work in earnest, probing the Martian surface over nighttime portions of the planet, where the local ionospheric interference is lowest. Most of the signal would be reflected directly back from the surface, but scientists hope the fraction that penetrates the surface will then be bounced back by layers of materials much farther underground.

High hopes for deep views

The MARSIS team's science goals range from "modest to ambitious," said Jeffrey Plaut, a researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory who is one of the principal investigators for the experiment.

"On the modest side, we are eager to see the interactions of our signals with the ionosphere and the surface of Mars," Plaut wrote in an e-mail to MSNBC.com. "The echoes detected from these two environments will be unlike any data obtained at Mars, and will undoubtedly contain some surprises.

“A bit more ambitious is to detect echoes (layer boundaries) that are unambiguously from the subsurface. This will be a major accomplishment for the experiment,” he continued.

“The fully ambitious goal is to characterize these detected boundaries,” he said — in other words, to “say something about their nature. This is where the search for water comes in.”

Plaut is cautious in his expectations: “It is not at all simple to look at a radar echo history and identify the composition of the reflecting layers. However, if there is a shallow water table in the right geometry, it may have a distinctive radar signature.” The experiment could conceivably detect water that is two or three miles (a few kilometers) beneath the surface.

“Convincing ourselves and our colleagues that this is a verified water detection will be quite a task,” he admitted, “but if we can do it, you might call it hitting a home run.”

Could subsurface water exist as liquid?

Planetary geologists have speculated for decades about exactly how warm it gets beneath the Martian surface, as the planet’s interior heat seeps toward the frigid surface. Some theories had suggested a region of "warm enough" rubble somewhere between the impervious bedrock and the frozen top layers, where water could migrate from the polar ice caps to the warmer equatorial regions. Other geologists told MSNBC.com they believed the layers would be frozen all the way to bedrock.

”We utilized similar models of the subsurface to get an idea of how deep we might detect liquid water,” Plaut explained. “These models depend on the existence (at least locally) of a saturated cryosphere, below which the temperature and the water abundance is sufficient for a groundwater deposit.

“Whether the water is part of a globally connected aquifer tied in with the polar deposits is not really important,” he continued. “The first question is, is the water there? The next would be, how did it get there?”

Tag-team radars

Next year, MARSIS could be joined by yet another ground-penetrating radar system in Martian orbit: the Shallow Radar, or SHARAD, experiment aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which is due for launch in August.

Like MARSIS, SHARAD combines U.S.-built and Italian-built hardware.

”The two differences are depth and vertical resolution,” he pointed out. “MARSIS was designed to probe deep, SHARAD to probe shallow. The advantage MARSIS has is that its low frequencies are the best for deep penetration. The advantage that SHARAD has is that higher frequencies can be used to obtain higher resolution of layers in the vertical dimension.

“One might expect that the shallow zone that SHARAD will investigate is less likely to contain liquid water than deeper zones, simply because it is colder near the surface. On the other hand, if the deep subsurface is devoid of water, SHARAD will better explore the shallow zones which we know contain water ice,” based on spectral observations from other instruments.

MARSIS will also observe the Martian ionosphere, and may even be able to detect ionization trails of meteors. SHARAD, which operates at frequencies about 10 times higher than MARSIS, will not be able to detect anything of interest along those lines.

Some scientists not involved with MARSIS have expressed concerns to MSNBC.com that the radar will not be able to penetrate nearly as deeply as is hoped, due to attenuation from iron-bearing minerals in the Martian soil. In the worst case, the visible depth may only be a tenth as deep as hoped. But even the skeptics expect the radar to see unexpected and unusual geologic features when it begins its observational program.