In the wake of the tsunami that devastated villages and killed tens of thousands in Southeast Asia on Dec. 26, there was a second wave of well-meaning volunteers rushing to the region to help rebuild.

It was in this pandemonium, MSNBC.com has learned, that an American with felony convictions for drug trafficking, sexual assault and check fraud surfaced to run an orphanage in Sri Lanka for more than two months. The judo master from San Diego, with a trail of aliases and deception, raised tens of thousands of dollars at the children’s facility before fleeing the country in the face of an investigation.

The man, Daniel Curry, 37, is actually Daniel Wooley, 41, and is also known as Daniel Taze — the latter a registered sex offender in California. He used the name Fogg while serving time in a Mexican prison for drug trafficking. Somewhere along the way, presumably after his release from prison in March 2003 he linked up with Michelle Curry, a computer professional in San Diego, and started using her surname.

No formal charges have been filed against Wooley, according to Harendra Da Silva, director of Sri Lanka’s National Child Protection Agency, who communicated with MSNBC.com by e-mail. But the agency is looking into several “major concerns”: “A man on a sex offenders list being in charge of an orphanage; fundraising in the name of tsunami for a non-tsunami orphanage; the Criminal Investigation Department has been informed of possible fraud.”

Michelle Curry, who is about 30, remains in Sri Lanka — banned from the orphanage along with all other foreigners for the duration of the investigation. She says the probe is completely unwarranted, sparked by backbiting among aid workers and corruption in Sri Lanka. As for her partner Daniel’s checkered past, she says: “He has completely turned around... He is putting everything into helping people.”

While no one disputes that the orphanage has been transformed in recent months, donors have distanced themselves from the project since learning of Wooley’s past. Volunteers who took part in that transformation are devastated by the scandal, worried both for themselves and for the children at the orphanage who are cut off from help.

Contacted by phone in the United States, Wooley denied any wrongdoing in Sri Lanka, and stressed the improvements made at the orphanage. In an angry harangue, he accused his critics of child molestation and child pornography, and said he was pursuing legal action for slander. He also threatened to sue this reporter for libel. Though Wooley agreed to a formal interview, he did not answer his phone at the scheduled time or return calls to reschedule.

Aggressive pace

Curry and Wooley arrived in Colombo on Jan. 18 from San Diego, where she had been a free-lance computer professional with experience raising money for aid projects. He had a marine services business in the city.

When they first visited Ruhunu State Receiving Home for Children in the devastated coastal city of Galle, the children were neglected and the facility was squalid. Curry said they produced an improvement plan based on her experience at a similar orphanage in Nicaragua, and formed a partnership with the government to improve the home. Wooley was to oversee construction work, and she was to raise money and take care of logistics, she said.

Ruhunu became a magnet for tsunami volunteers and donors who were looking for a place to contribute. Of the 40-50 children at the orphanage, only one was actually orphaned by the tsunami, visitors were told, but the need was glaring. Wooley and Curry set about hiring new staff, and writing up complaints against workers they judged to be incompetent or negligent.

The children were treated for scabies, staph and impetigo. The home’s leaking roof was repaired, its well was fixed and a fence was built around the facility.

The work generated a whirl of publicity. The musician Sting and his wife, Trudie Styler, an ambassador for UNICEF’s national committee in Britain, visited. Sting made a personal contribution, the American Red Cross contributed aid packages for the children and a local paper carried a glowing account of the couple’s work.

Donations poured in.

Tension in the ranks

But the atmosphere at the home was uneasy. There was a steady exodus of volunteers put off by Daniel and Michelle.

Local workers referred to Wooley as “King Daniel” because of his imperious attitude.

“They were basically running it like a plantation in Civil War days,” says Debbie Nordstrom, a 46-year-old financial consultant who volunteered at the orphanage in February. “(Daniel) would line up the local workers every morning and say ‘You, you and you … and then yell, ‘the rest of you, get the hell out of here!’”

“He treated them like slaves,” she says. “It was horrible.”

“I was a hard-ass,” Wooley told MSNBC.com in one phone conversation, “but I had to be to make things happen. I stopped people who were stealing from children every single day.” He says he hired and fired to weed out workers and volunteers who weren’t working out.

Some of the volunteers kept their distance.

“Nobody really liked Daniel, but what (he and Michelle) were doing seemed really positive,” says Karen Helms, a volunteer from Utah who worked with the children for two weeks in February. “Kids were definitely getting better care. We saw so much improvement in the short time we were there.”

But people who heard Daniel’s stories didn’t know what to believe. He told Helms that he had done secret military work in Utah. One donor, Nick Keegan, said he understood that Michelle and Daniel had run an orphanage in Malawi prior to their work in Sri Lanka. Kent DeWitt, a retired fireman from Seattle who worked with Curry and Wooley early on but left after a falling out, said Wooley claimed he had worked for the United Nations.

Their story as a couple was also confusing. Curry says she and Wooley were married in Las Vegas in 2002. But Wooley was not released from prison until March 3, 2003, after serving nearly four years in Mexican prisons. His divorce from his ex-wife was not finalized until Oct. 26, 2004, a few months before his arrival in Sri Lanka.

Tears and money concerns

Adding to the tense atmosphere, Michelle and Daniel fought frequently, volunteers said, and she would often end up in tears.

The couple’s finances are equally perplexing. Curry told MSNBC.com by phone that she had raised and invested $50,000 in the orphanage.

Critics of Wooley and Curry say that amount is far more than required for the work done at the orphanage.

Among the skeptics is Jennifer Longheyer, a behavioral consultant who works with autistic children in Seattle. Longheyer and her husband, Scott, oversaw the construction of a library and renovation of a preschool, medical clinic and computer room to create the Boosa Youth Center in Sri Lanka, complete with teaching materials and furniture — all for about $2,098, and in a few weeks. Boosa serves 500 to 700 people a month with a variety of classes, medical care and first-aid training. Its operating budget is just under $11,000 a year.

“With the amount of money (Curry and Wooley) got, and the amount they had in bank accounts, they should have fixed the home and moved on,” says Longheyer.

Michelle Curry agreed to send the orphanage accounts to MSNBC.com to review, but has not done so. After an initial phone conversation and e-mail exchange, she did not answer e-mail, and calls to her cell phone in Sri Lanka did not connect.

Curry raised money for Sri Lanka aid work through a spontaneously created organization called the Helix Foundation, which was also soliciting funds for four other projects, including a center for abused women.

Hand-delivered cash

Total donations to the orphanage are unknown, and may never be tallied in their entirety.

“Money was just pouring in,” said volunteer Helms, who witnessed hand-delivered donations at the door, many of them small amounts from both locals and foreigners. “On average — maybe 1,000 rupees — about $20. That goes a long ways in Sri Lanka.”

But confusion surrounds larger contributions as well. One organization, Adopt Sri Lanka, says on its Web site said that it has received more than $75,000 in donations for Ruhunu, and a short blurb on the project says the orphanage's needs are "well covered for the time being.”

Curry told MSNBC.com that Adopt Sri Lanka gave the orphanage about $7,000.

But Winnie Hsia, a young business school graduate who worked as the orphanage's account manager from February through mid-April, said that Adopt Sri Lanka had donated about $20,000 — which was the largest donation to Ruhunu that she was aware of.

Hsia, who continued working on the books for a short time after returning to the United States, seemed unaware of at least one larger contribution made weeks before she left Sri Lanka. MSNBC.com confirmed that Friends of Unawatuna, a grass-roots organization based in Britain that formed after the tsunami, gave 15,000-pounds ($27,180) sometime in March for Ruhunu's improvement.

“The need was just so great that the project seemed like a no-brainer,” says Nick Keegan, a trustee for the group.

Adopt Sri Lanka did not respond to queries seeking clarification of the amount of money it gave to the orphanage. And the organization's founder, resort owner Geoffrey Dobbs, could not be reached for comment. The blurb on its Web site noted that Ruhunu was undergoing a "change in management structure" and said that Adopt Sri Lanka was "reassessing" its involvement.

Books in disarray

Hsia said she believed that all the donations to Ruhunu were being legitimately used for improving and running the orphanage.

But she said that logging the donations fell behind because of the frenzied pace of the renovation. And she said that the only way that she would know about some of the contributions was if Michelle Curry told her, since donations were deposited in Curry’s personal account.

“This is another reason I resigned,” said Hsia, who left Sri Lanka on April 16. “As much as I have to assume a level of accountability … I wasn’t 100 percent privy to everything.”

In an initial conversation, Hsia agreed to send Ruhunu’s financial records to MSNBC.com, but later said she had changed her mind, and that she would not engage in further conversations with the reporter.

A question of identity

Eventually, the team of volunteers unraveled as questions emerged over Daniel’s identity and background.

“It made me wonder: What’s the point of the lies?” says David Al-Adra, a medical student from Canada who volunteered at Ruhunu for two months. “I gradually came to understand that they weren’t as legitimate as they claimed.

A report in the local newspaper in April revealed that the man known as Daniel Curry had a criminal background under other aliases.

“We all shared housing, so I thought I really knew him, but maybe I really didn’t,” Hsia says of Daniel.

Friends of Unawatuna is distraught by the scandal. The group, representing individual donors and volunteers, formed after many of its members witnessed the tsunami disaster first-hand while on vacations in Sri Lanka. Now, says Keegan, they worry that their other projects in the country might be hurt by the scandal.

Longheyer and her husband, Scott, originally planned to work on Ruhunu, but decided their funds were better spent elsewhere. They said they ended up filing a complaint with local police after Daniel Wooley, in a dispute over a rental apartment, threatened to get their visas revoked.

“The threat was … ‘I’ll get you thrown out of the country,’ ” says Long. “He supposedly had all these powerful friends. That’s what everyone said.”

Time in a Mexican prison

San Diego court records show that Daniel Wooley (Daniel Nichalas Taze) was convicted in 1998 of assault with intent to rape and sentenced to two years in prison. As a result of his conviction, he is a registered sex offender in California. Other charges of kidnapping and forced oral copulation were dropped in a plea deal.

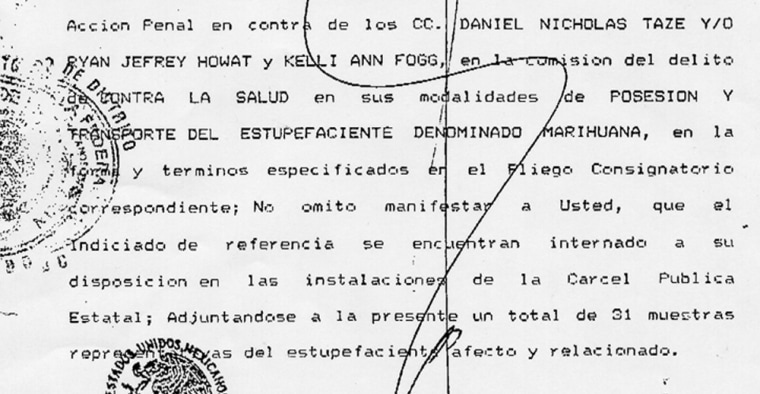

In August 1999, Wooley and then-wife Kelli Fogg were arrested in Mexico in possession 61 kilograms (nearly 135 pounds) of marijuana and sentenced to five-year prison terms.

The prison facility was like a small town — with families, schools, video stores, drug houses, and prostitution. Fogg, now 36, says that while she and Wooley were in the prison, they managed to build a small church and provide shelter for newly arrived Americans.

Inside the prison, Daniel also treated infections, helped children and fed people, Fogg says. “He often does the right thing, but for the wrong reasons,” she says. “He’s a control freak.”

“He was constantly bribing guards to get things done, to make life a little easier for us,” says Fogg.

Sent to maximum security

When 1,800 federal agents stormed La Mesa Penitentiary in mid-2002 to shut it down, Wooley (recorded as Jesse Howard Daniel Nicholas Taze) was sent to a maximum security prison along with 43 Mexicans considered by authorities to be extremely dangerous. In March 2003, he was transferred to a federal prison at La Tuna, Texas, (on record as Daniel Andrew V. Wooley Taze), under a U.S.-Mexico prisoner exchange and was released.

Fogg says the prison raid was a huge relief because it separated her from her husband. Since her release in December 2003, she has been in therapy, in part for what she describes as years of emotional and physical abuse by Wooley. She now visits U.S. prisoners in Mexico weekly with San Diego-based chaplain David Walden.

Walden, who has been working with U.S. prisoners in Mexico every week for 12 years, knew Daniel well during his prison term. He is skeptical about a professed turnaround.

“I saw no indication of a conversion,” says Walden, referring to a meeting with Wooley shortly after his release from prison in mid-2003. He says Wooley approached him for help on an orphanage project in Puerto Rico, but he declined.

“I told him, ‘not until you show me five years of accountability out here … and references that show a change of character, then we’ll talk. Give me some history, pal.”