The Rev. Keith Tonkel, a white United Methodist, knew signing a simple statement against racism could put his life and those of his colleagues in peril. It was four decades ago and Mississippi remained a stronghold of segregation.

He signed the document anyway.

The backlash was swift for him and the 27 other white Methodist clergy who added their names to the “Born of Conviction” declaration. Some were ousted by their congregations and fled Mississippi under death threats. Others left freely. Some stayed and fought.

On Monday, for the first time, they will hold a reunion in Mississippi. At least 13 plan to attend the reunion. Eight have died.

The 1963 statement, benign by today’s standards, was explosive in its time. The ministers denounced racism, communism and the threatened closure of public schools that were facing integration.

“Our Lord Jesus Christ teaches that all men are brothers,” they wrote. “He permits no discrimination because of race, color, or creed.”

They mailed the document to newspapers and waited. Then came the fallout.

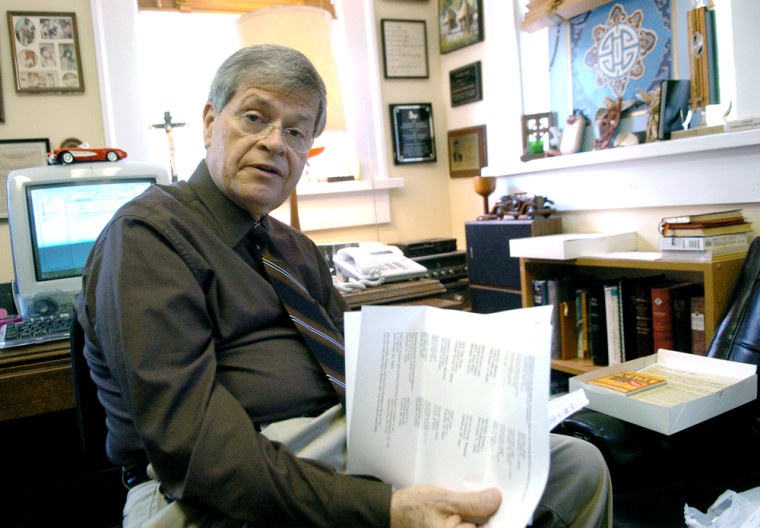

Tonkel was among those who stayed, despite the public reaction.

Timely gathering

“I said to them, ’I’m only signing this thing with the understanding we’re committed to staying in Mississippi,”’ said Tonkel, 69, who has led the interracial Wells United Methodist Church in Jackson for 36 years. “How can you flesh out a conviction if you’re absent? I thought our responsibility was to see what we can create that would be inclusive.”

The gathering coincides with the Mississippi Methodist Conference’s annual meeting in Jackson. It also occurs a week before the opening of the Philadelphia, Miss., murder trial of a reputed Ku Klux Klansman accused of the 1964 murders of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, civil rights volunteers who helped blacks register to vote.

Four clergymen — Gerald Trigg, Maxie Dunnam, Jim Waits and Jerry Furr — were the original authors of “Born of Conviction.” They secretly met at Dunnam’s southern Mississippi river camp and worked overnight on the document.

Condemnation in the press

After the statement was published, columnists in state newspapers wrote scathing editorials condemning it.

“This was perceived as liberal troublemakers rocking the boat. It’s not the ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ or anything like that. The main thing it did was remind the Methodist Church of their social creed,” said Joseph Reiff, a religion professor at Emory & Henry College in Virginia.

The Methodist Church, like most white denominations in the South, had not at that time spoken out against the beatings, lynchings and mistreatment of black Americans. Yet, the denomination’s official position condemned racial discrimination.

The statement was released months after rioting erupted on the Oxford campus of the University of Mississippi when James Meredith became the first black student to enroll there. Just a few months after the statement was published, Mississippi NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers was assassinated in Jackson by white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith.

‘Lack of support’

Reaction to the ministers was far less severe, but some were threatened or had their tires slashed.

“What was more difficult for many of these folks was the lack of support that they got,” from some leaders and church members, Reiff said.

The Rev. Jim Nicholson, who signed “Born of Conviction” and organized the ministers’ reunion, remembers a struggle of conscience. As minister of a small church in Byram, just outside Jackson, Nicholson tried to change the attitude of his white congregation.

“I delivered a sermon there called ’A Trail Through the Wilderness.’ I laid it on them pretty heavy,” said the 82-year-old clergyman. “They boycotted me from then on and refused to pay me any more, but they let me stay in the parsonage.”

After he signed the document, the congregation voted him out. Nicholson eventually left the state for Iowa.

Striving to do more

Dunnam said the ministers hoped to do more than integrate churches. In Gulfport, where he preached, black people were intimidated by police who forbade them to openly meet with whites.

Dunnam recalled a midnight phone call he received from the Rev. Henry Clay, a black Gulf Coast minister, after Dunnam had visited Clay’s Sunday service. That night, the police invaded Clay’s home and demanded to know the name of every white person who was at the church service.

“Henry wouldn’t give him my name without my permission,” Dunnam said.

Dunnam, 70, who recently became chancellor of Asbury Theological Seminary in Kentucky, said he left Mississippi after the statement was published because “there was absolutely no support from the leaders of the church.”

All these years later, he said the nation remains divided by race.

“At least the governmental and civil laws have been changed. That’s the difference,” Dunnam said.

Most of the preachers continued fighting for racial justice, said Waits, who lives in Atlanta. “I think that’s, in a sense, the reason some of us want to re-gather and remember,” he said.