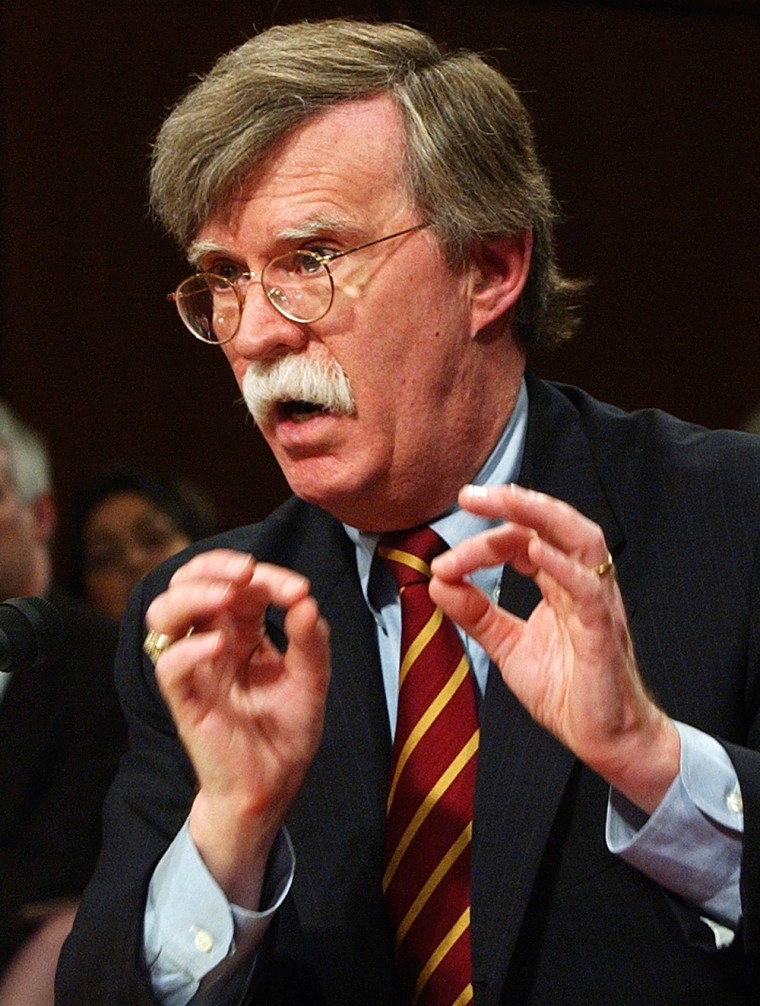

UNITED NATIONS — The 190 ambassadors and legions of lesser diplomats and staff members of the United Nations are watching warily as Senate Democrats try to forestall the confirmation of John Bolton as U.S. ambassador to the world body. Yet far from being elated by the sleeplessness this may cause Bolton, who has a long record of questioning the U.N.'s relevance, diplomats and officials here say the last thing they want is to stir up a hornet's nest of American opposition to the organization.

True to their reputation as diplomats, public discussion is discreet. But in less formal settings, like the coffee bar where U.N. delegates have a smoke between sessions, the Bolton topic stirs a mix of emotions at an institution that many people feel has been alternatively vilified and ignored by the present U.S. administration.

On the one hand, says a senior Asian diplomat, sipping an espresso between meetings on HIV/AIDS funding, there was a sense that many at the U.N. were hoping the Democrats who oppose Bolton’s nomination would prevail, forcing President Bush to nominate a compromise candidate, perhaps a career diplomat cut from more familiar cloth to those who roam the halls of the U.N.’s headquarters.

“After all,” the ambassador says, “the Iraq war should have taught the president by now that even the most powerful member of the United Nations can’t get its way without compromise.”

The message not the man

But this ambassador and other officials stress that the man who represents the United States is far less important than moving the discussion of the U.N. in America beyond what one diplomat called “the vilification of the attack dogs of the right.”

“There is no question of isolating the American ambassador because someone may not like him; the Americans are just too important,” the diplomat says. “What I would like to see is an honest portrayal of the U.N. to the public, that we are trying to make things work better.”

Over the years, Bolton has become known for stinging statements on everything from alleged Cuban weapons of mass destruction to the viability of the U.N. itself — he once famously suggested that "removing the top 10 floors from the United Nations building would have no effect whatsoever." He also has been highly skeptical of European efforts to negotiate with Iran over its nuclear weapons program, and he led the Bush administration’s unsuccessful effort to replace the head of the U.N. nuclear agency, IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei, among those who warned of the flimsiness of prewar evidence about Iraq’s WMD programs.

Bolton also served as deputy secretary of state of international organizations under Bush’s father in the early 1990s. Many remember his successful push to get the United Nations General Assembly to repeal its highly controversial “Zionism equals racism” resolution, passed in the emotionally charged wake of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. He has described the vote to repeal that resolution as a highlight of his career.

Bring it on

The political tussle over the Bolton nomination comes at a critical time for the U.N., still numbed but also somewhat invigorated by the 2003 debate over Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction.

With America the 2,000-pound gorilla of the U.N., there’s little concern at the U.S. mission to the U.N., which Bolton will run if confirmed, that somehow the angry rhetoric of the confirmation hearings will impact the next ambassador’s ability to get things done.

“Everyone here understands that there is a political element that goes into the approval process in America,” says Rick Grinnell, spokesman for the U.S. mission here. “When Mr. Bolton is approved, everyone will be eager to work with him.”

A key question for the next American ambassador, then, will be U.N. reform. Reacting to both the Iraq debate and the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan has tabled the most sweeping reform proposals ever attempted here in hope of having at least some major changes approved when world leaders gather in September to celebrate the 60th opening session of the world body.

At least some of the proposals have the support of the United States, and Bolton, if confirmed, would play a major role in shaping them. At the same time, however, Annan’s prestige has faltered in light of revelations that his son benefited financially from the Iraq “oil-for-food” program that was meant to allow the economically strapped nation to feed its people during U.N. sanctions against the Saddam Hussein regime.

Can he be effective?

Still, many American career foreign service officers view Bolton's choice as proof the Bush administration is out to kill the U.N., or at least make it impossible to influence policy.

“By undermining the U.N., the administration can claim its argument that the organization is incapable has been proven correct,” says Dennis Jett, former U.S. ambassador to Peru and Mozambique and now dean of the University of Florida’s International Center. Jett and others argue that Bolton's performance in his current post, as the State Department’s chief official on non-proliferation, should be enough to raise serious questions.

“The question is, ‘Are you effective?’” says Jett. “Bolton clearly is not. The total failure of [last month’s U.N. Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty] conference demonstrates that, not to mention our failure to work effectively with other countries to prevent Iran and North Korea from getting nuclear weapons.”

If there is any glee about Bolton's nomination problems here, though, it appears to be tempered by realpolitik — that is, a knowledge that the American ambassador, no matter who he is, will wield unequal influence once installed.

“There’s a sense of ‘so what’ about it,” says a U.N. official, who would not speak about Bolton’s nomination on the record. “Most people here saw the last ambassador, John Negroponte, as a bull in a china shop. So now Washington is sending a ‘wild bull’ to the china shop? People don’t see that much difference. Mostly, I think, they just want to see a new American ambassador here and the United States more engaged in what the U.N. does.”